A guidebook published by Rehva considers the potential of heat recovery from wastewater, with an emphasis on shower appliances.

Rehva guidebook No 34, Instantaneous wastewater heat recovery in buildings (bit.ly/CJWWHRS25), offers a technical reference for the integration of these systems in new and existing buildings.

It brings together analysis and practical design guidance to support the implementation of wastewater heat recovery systems (WWHRS) as a low-risk, high-yield strategy for improving energy performance.

Domestic hot water (DHW) demand in buildings remains significant – estimated at between 12 and 20kWh.m–² annually – and is becoming proportionally more significant as building envelopes become increasingly efficient.

A substantial share of DHW energy use comes from showers, where wastewater typically leaves the drain at around 35°C. The temperature differential between the waste and incoming cold-water supply creates an opportunity for energy recovery.

The guide introduces instantaneous WWHRS as a practical and accessible means of capturing this waste heat. Functioning much like heat recovery units in mechanical ventilation, WWHRS can recover up to 60% of the energy used during a shower.

These systems can be compact and durable, and are likely to contain no moving parts and be designed to require minimal maintenance. They recover heat without compromising shower performance – unlike some water-saving devices that reduce flow or temperature.

At their core, WWHRS operate as heat exchangers, transferring energy from warm wastewater, going to drain, (primary side) to colder incoming (and probably mains) water (secondary side) without the two streams mixing.

Efficiency is determined as the ratio between the actual heat transferred and the theoretical maximum recoverable heat, and is affected by the flowrates, temperature profiles and design characteristics of the heat exchanger. Most WWHRS employ highly efficient counterflow designs and are evaluated using established methods, such as the number of thermal units approach.

Shower parameters vary – typical flowrates range from six to 24 litres per minute, with outlet temperatures between 38 and 42°C, and mains (cold) water temperatures between 5 and 25°C. Drain water is typically 3-5K cooler than the outlet temperature because of in-cubicle losses. The guide presents this data alongside methods for calculating system performance under steady-state and transient conditions.

Three hydraulic connection schemes for WWHRS are described:

- Scheme A preheats incoming cold water before it reaches the inlets to the shower mixer and the local water heater. It operates with balanced flows (primary flowrate equals secondary flowrate), which enhances efficiency and makes it the most effective configuration – especially when installed close to both the shower and the heater.

- Scheme B preheats only the cold water feeding the shower mixer, resulting in an unbalanced flow. It is easier to retrofit, but limited to localised impact.

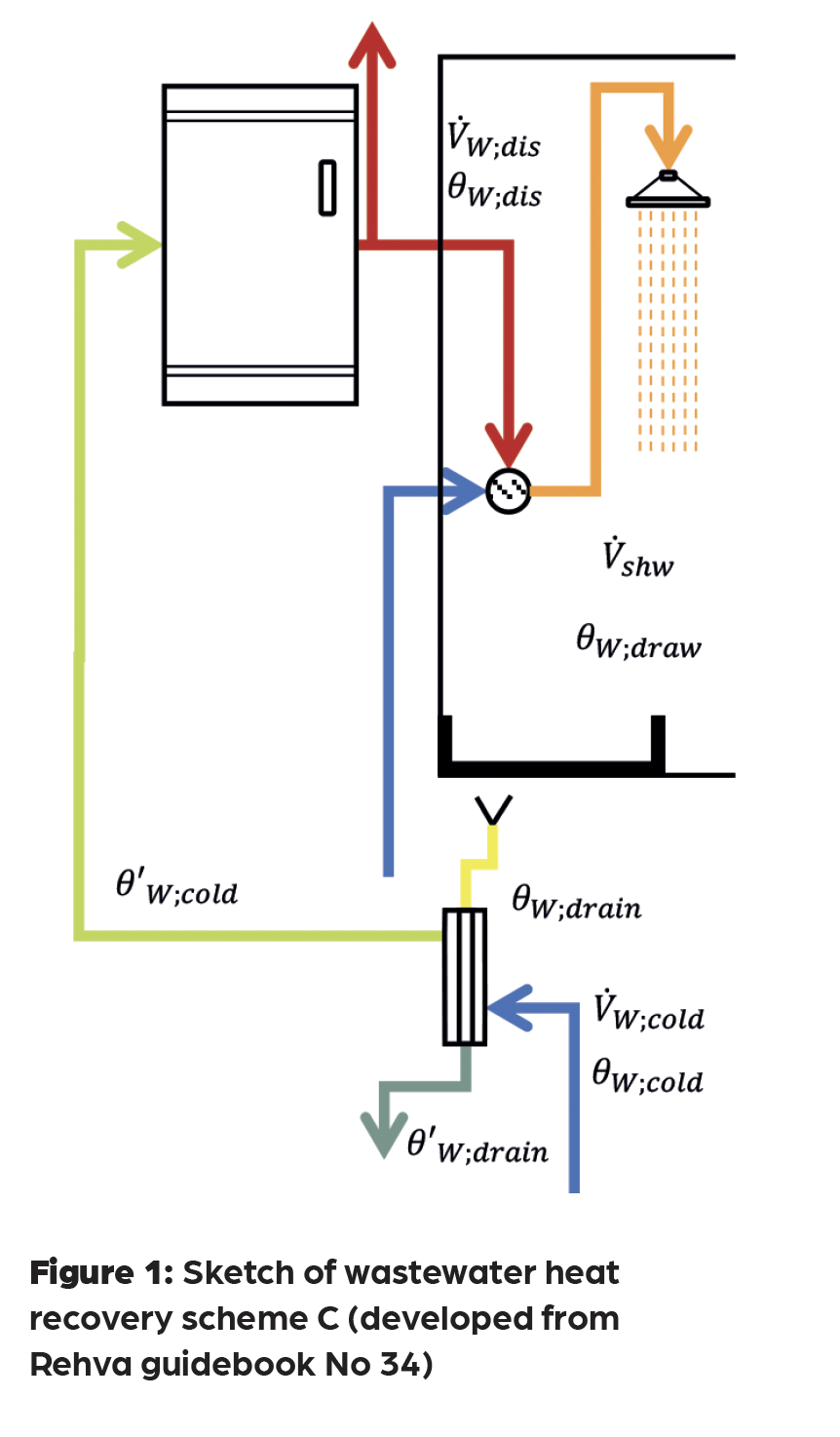

- Scheme C (as illustrated in Figure 1) preheats only the cold feed to the water heater, (so unbalanced conditions). This scheme is preferred in centralised DHW systems and poses a lower legionella risk.

The guide includes health and safety considerations, with particular emphasis on the risk of legionella proliferation, as water between 25°C and 50°C is particularly conducive to legionella growth, especially in stagnant conditions.

As WWHRS units preheat water, there is a potential risk in schemes where preheated water is not further treated by a water heater. Risk-mitigation strategies include minimising the volume of vulnerable preheated water (ideally below three litres), ensuring rapid cooling below 25°C post-use, and avoiding insulation that may slow cooling.

Some WWHRS feature rapid cooldown characteristics (eg, <25ºC in 45 minutes, as per German DIN 94678 Devices for heat recovery from shower wastewater), while active measures – such as automatic draining or manual flushing – are also discussed.

Scheme C is identified as presenting the lowest legionella risk because the preheated water is reheated to safe temperatures. The guide also recommends avoiding biofilm-promoting materials (typically certain plastics), favouring copper and using certified products.

Cross-contamination is considered low risk under normal operation, but safeguards such as double-walled construction and leakage alarms are recommended to address potential backflow or siphonage. Other safety topics covered include fire resistance, acoustic performance and protection against cross-contamination or leakage. The guidance notes that standard installation and commissioning practices are usually sufficient to ensure safe operation, particularly when products are certified and installed in accordance with manufacturer’s guidance.

The guide includes a well-illustrated section on installation, where vertical systems are identified as typically providing the best performance and cost-effectiveness, although they require substantial installation height. These are noted as being generally maintenance-free in greywater applications.

Horizontal systems are more compact – some as shallow as less than 10cm below the tray – so may be used in many retrofit applications, though they are more prone to clogging and may require periodic cleaning. Active vertical units using a pump provide additional flexibility for layout and performance, but introduce energy and maintenance demands.

The selection of scheme and system type is closely tied to the DHW system layout, and these are discussed in the guide:

- Decentralised systems can benefit from all three schemes depending on layout. Scheme A is viable where distances are short.

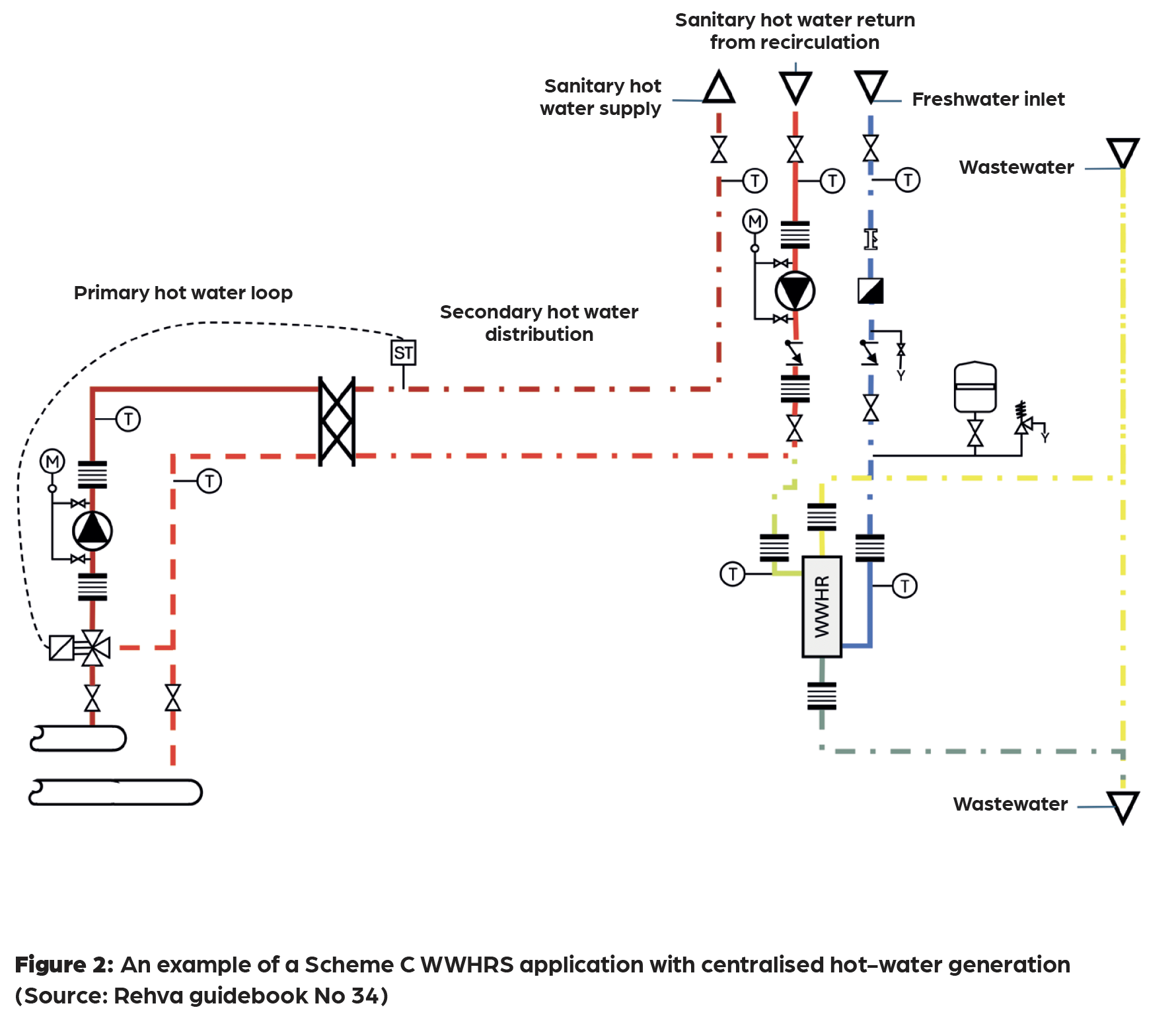

- Centralised systems typically use Scheme C, illustrated in Figure 2, because of its compatibility with centralised hot-water production and presenting a lower health risk. Larger systems may use multiple WWHRS units, with bypasses to manage peak flows or clogging. Hybrid approaches combining Scheme C and Scheme B can offer cascade benefits.

- Buildings with fixed-temperature DHW systems (such as leisure centres) may favour Scheme B or A with large-diameter exchangers.

- High-rise buildings may require zoning and multiple schemes to accommodate pressure and layout constraints.

- Independent greywater drainage is noted as offering more flexibility and system options. Where greywater and blackwater are combined, WWHRS compatible with blackwater (usually vertical coil-on-pipe systems) are required. These involve greater installation effort and are more clog-prone, but can be used as part of soil stack replacement.

The level of intervention in a building project significantly affects what is feasible:

- Shallow renovations can incorporate plug-and-play horizontal systems (typically Scheme B) with modest efficiencies (~40%) and minimal plumbing changes.

- Medium renovations, such as full bathroom refits, allow for horizontal or active vertical systems.

- Deep renovations and new builds provide the best opportunities for optimal WWHRS integration, especially passive vertical systems serving multiple showers, ideally located in dedicated service zones.

These systems can offer opportunities for significant savings without impacting the users’ showering experience, and can be integrated across a wide range of building types and renovation scales. The guidebook is a valuable resource for building services engineers exploring the application of this technology into carbon-conscious building design.