Building information modelling (BIM) is not – as some may believe – about creating a 3D model for its own sake; nor is it an add-on process. BIM is fundamental to the way a project is set up and run.

Adhering to this philosophy has resulted in Skanska making impressive progress in its use of BIM, and is the reason why its project – The Monument Building, in London – is of particular note. As the developer, customer and owner, Skanska has been able to push the boundaries of BIM, using Level 2 throughout the design and construction process, and moving towards creating a single collaborative, online model, which includes construction sequencing (4D BIM) and cost (5D BIM).

Project manager, Tim Walsh, and BIM coordinator, Ainara Thompson, say the building was kept on a tight construction schedule, not least because all of the project partners engaged with BIM. They reveal the challenges and opportunities of the process, and why BIM is a fundamental part of any Skanska project.

Level 2 BIM

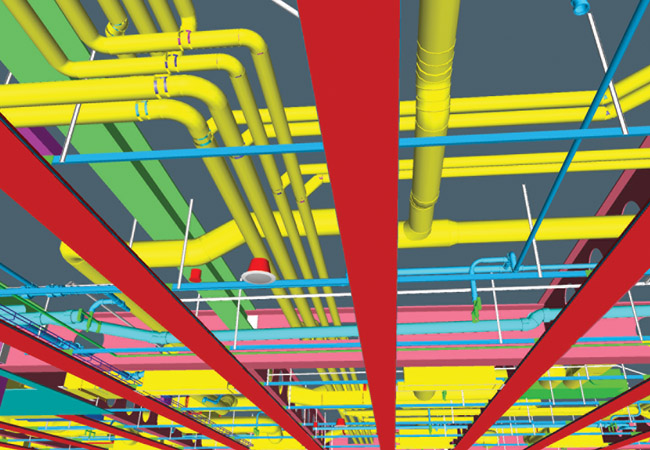

Effectively using the limited space of The Monument Building’s basement – where 90% of the building services plant is housed – was a major test for the team.

‘We didn’t dig down, so it was fairly congested down there, with huge areas of ductwork – so coordination has been interesting,’ says Walsh, who acknowledges that BIM played a key role in both clash detection and programming works. ‘With this being a Skanska development, we wanted to push BIM further than most of our traditional customers would ask for,’ he adds. ‘It was a big challenge in the beginning because the architects and design team were unsure about where we wanted to go with the BIM deliverables.’

Walsh says the most problematic aspect of the process was integrating the mechanical, electrical and plumbing (MEP) services elements with the design model for the Level 2 federated model.

Unlike architects and consultants, who model in Revit, Skanska create theirs in MEP CAD-Duct – or CADmep – a manufacturing tool that sends information directly to the ductwork fabrications unit, where parts can be cut straight from the model.

‘We have had to do a lot of work taking the design model and turning it into a working, operational one,’ says Walsh. This was done with the help of a full-time BIM coordinator, Ainara, who has owned all the models and managed coordination between them.

Project team

Customer: Skanska Project Developments Limited (SPDL)

Architect: Make Architects

Building services engineer: Arup

Structural engineer: Arup

Fire engineer: Arup

‘The design team’s models were very easy to combine because they were all using very similar software. But when it came to the construction issue model, we had to take out the Revit M&E design model and input our own version, which was in CADmep. That allowed us to manufacture and prefabricate directly from the model, which we would not necessarily have been able to do if we had continued on a federated model.’

Autodesk Fabrication CADmep uses databases of parametric and manufacturer-specific components and fittings for detailing. Typically, these components have been restricted to Fabrication products.

Walsh says there is now software – such as CADmep 2016 – that allows users to share models created with these components more seamlessly with Revit. ‘We were too early in the design phase for that,’ he explains. ‘But we will certainly use it for the next job, where we will take on all the design information and transfer it into a working model, rather than scrapping any of it.’

Programming and costing

Skanska used the model for quantity takeoffs of some build items, including blockwork. This is the first step in the process of 4D BIM.

The quantity takeoff algorithm looks at each piece of geometry within the 3D BIM and calculates its properties – such as surface area and volume. This drives more precise model-based schedules for deliveries and installation, and 5D cost estimates, because the quantities are properly defined.

The ‘smart’ materials that made up The Monument Building model could be interrogated to find out the geometry and property of each component. ‘You can then get the model to do a takeoff of all the area of that material in the building. It strips away everything else and just gives you the required data, which you can import into a spreadsheet, giving you the total quantities of – for example – blockwork or ceilings,’ says Walsh.

This blockwork data was then checked against the sub-contractors’ prices, says Walsh. ‘So we were able to have a conversation with them about areas where they had looked at things differently to us.’

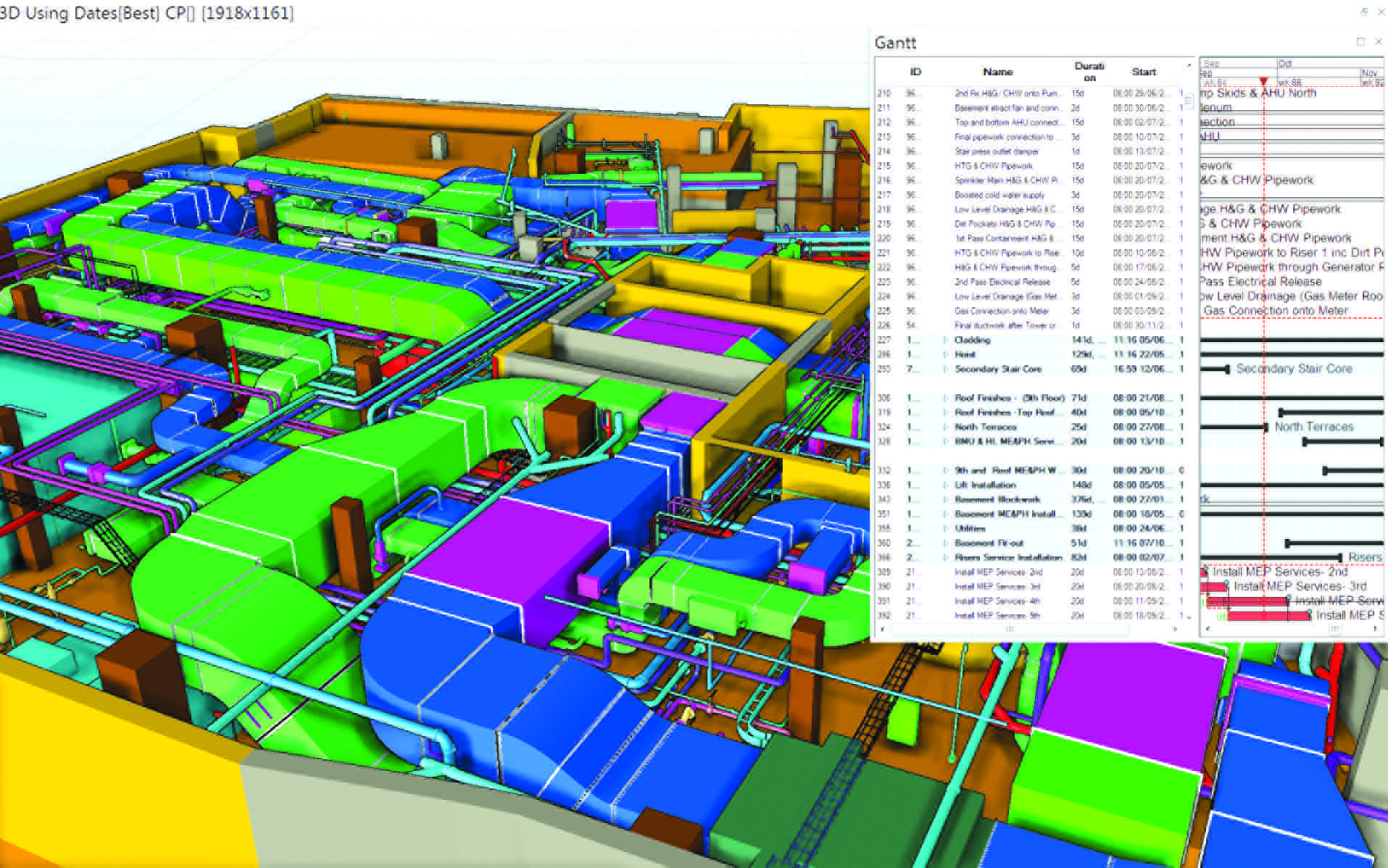

A 4D model of services in the restricted basement

Ultimately, as the design moves through iterations and the level of detail increases in the model, the estimate hones in on the final number. This type of analysis is much more intuitive than simply counting windows, doors, floors, ceilings, and walls; you can quickly see which elements have been costed and those that still need attention. It also allows owners to see how areas of the building are contributing to the total cost of the project.

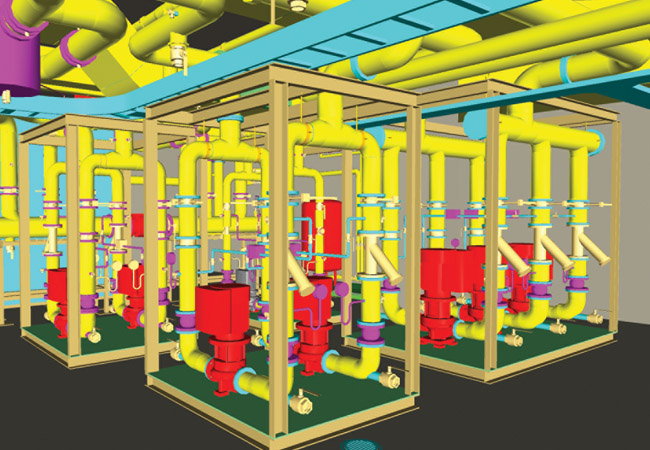

To achieve 4D planning, Skanska linked the programming software with the 3D model, breaking it down into certain tasks. ‘Being able to schedule works according to the model really helped in the basement,’ says Walsh.

‘We cut through layers of the model, took off certain services and gave the model to the guys on site and said: “This is your week’s worth of work – this is what you can and can’t install – because if you install from the second section, you’ll prevent someone else from installing.”’

Thompson adds: ‘The good thing about this technology is that you can update the program on one side and the model on the other. But you don’t have to start again because, as long as you keep the data links, it’s an automated process.

‘So, if you move a door, the program recognises that it has moved and retains the link to the activity.’

The ‘link’ is the association between a 3D CAD object and its location in a construction project – giving Skanska the ability graphically to review its programme.

Heating, ventilation, air conditioning and power installation, designed through BIM

For the next project, Thompson says she would add the app for the program, so the planner can go around and capture progress on site using an iPad.

Knowing where to invest your money and where not to is a lesson learned, says Walsh. ‘BIM is an endless amount of information and you can quite easily lose money trying to chase a solution to a problem that could be solved with experience and a bit of personal knowledge. For example, we could have modelled every plasterboard stud, but decided that this entailed a lot of upfront design work for an installation that was relatively flexible.’

Towards 6D BIM

Knowing who the potential facilities management (FM) companies are going to be is a key issue, says Thompson. ‘It’s important to get customers and facilities management teams engaged earlier, so they can set the requirements for all the asset tagging and an agreed list that covers the naming conventions.’

For The Monument Building, a facilities management company was not specified, so Skanska’s in-house facilities services team offered support, using its own referencing structure, including naming, organising and scheduling assets.

The Monument Building

Located next to the Monument to the Great Fire of London, the building has 88,000ft2 of office space and 4,000ft2 of retail space on the ground floor.

Designed by Make Architects, the office space is split over 10 floors, with terraces at levels 4, 5, 7 and 9.

The building is constructed to achieve a Breeam ‘Excellent’ rating, and features a green roof, a 54m2 photovoltaic panel array – producing 8,547KWh of electricity per year – LED lighting throughout, an intelligent lighting control system and a twisted steel-fin façade to reduce heat gains and ‘mask the new from the old’.

It also incorporates a fire-protection system that is unique to a building of that size. The strategy works on positive and negative pressures, with positive pressures in the single-core fire lobby and negative pressures on the floorplates. Walsh says: ‘It’s a reverse system that keeps smoke out of the core, rather than pulling it into the core and out of the building.’

The building has a traditional four-pipe fan coil system on the floor, and air-cooled chillers and gas-fired boilers.

Walsh says: ‘Other than the fire-protection system, we’ve tried to keep everything very simple on this project. We’re land developer and builder, so we were able to affect the design at a very early stage and, because of that, we’ve managed to simplify quite a lot of the systems.

‘It’s trying to take away a lot of the bells and whistles that are often installed for unnecessary reasons, and almost strip it back to the essentials, while still providing a comfortable working environment for the tenant.’

Walsh says: ‘If another facilities company were to come in, then our digital operating and maintenance information could be handed over to them. However, they may wish to use their own classification system.’

As well as the soft landings agreement – which includes a settlement period and regular visits by Skanska to ensure the building is operating as intended – Thompson is working with digital operation and maintenance (O&M) manual writers, Edocuments, to create a digital cloud-based guide for future FMs.

The digital O&M is connected to the combined 3D CAD model that enables FMs to access or update asset maintenance requirements or defects.

Walsh says Skanska has also been barcoding assets, which allows FMs to scan them in the plantroom and instantly browse relevant regimes in the searchable O&M manual. In the office, they would be able to open the 3D model, click on the item, and bring up the manual and asset register.

Thompson says: ‘I think that’s something quite groundbreaking. Even the O&M manual company is experimenting with us, so we’re going on the journey together.’

Planning the pump sets installation schedule in BIM avoided trade clashes and minimised access challenges

The operation and maintenance manual is live, so any redundant information or defect – a leak, for example – as well as future fit outs can be instantly updated with an iPad, adds Thompson.

Skanska has a full training programme for the O&M manual, and is looking at the potential for using video.

‘If there’s a specific maintenance requirement for a piece of kit and the user needs specialist training, often the person you train isn’t the one who will be doing it in six months’ time,’ Walsh says. ‘So we are looking at creating training videos embedded in the O&M manual.’

Walsh adds: ‘We’re seeing the benefits of BIM and so is the customer, so they can sell it to their potential tenants. They’ve got the information installed in the model, so it’s not a case of getting everything remodelled – just a case of updating their changes.

‘It’s taking a life-cycle approach to the building, rather than just building it and walking away.’

Collaboration

Skanska used cloud-based construction field management software Autodesk BIM 360 Field to manage defects, and this helped the whole project team to collaborate more effectively. Walsh says: ‘It allows us to open up the model and drop a pin in it, to show where the defect is, attach a photograph or description, and name the subcontractor that will rectify the defect.’

That defect automatically gets sent to the company to resolve, after which they are able to go out with their iPads and change its status, says Walsh. On that system, all contractors and subcontractors have access to the 3D models. ‘In theory, they should never be working to superseded models because the latest version is on their iPad.’

Thompson adds: ‘We’re trying to get BIM and digital technology engraved into everything, and not to be a stand-alone entity. Some people think BIM is a separate thing, but it’s embedded in the business and in different roles.’

BIM Levels

There are four different levels of BIM maturity. The higher levels are:

BIM Level 2 – the creation of a managed 3D environment with data attached, but created in separate, distinct discipline models that may originate with the customer, the building services engineer or the architect. A federated model is an assembly of these to create a single model consisting of linked – but distinct – component models. This level of BIM may use 4D construction sequencing and/or 5D cost information.

Level 3 involves the creation of a single, online project model, worked on – and available to – all parties. Interoperability and collaboration is still a barrier to this, and the resulting copyright and liability issues may be more difficult to resolve.

Collaboration as a result of BIM has taken a real step forward, says Walsh, not just for Skanska, but for construction as a whole – from the customer down to the contractor. ‘We’re seeing a willingness from contractors to get involved in BIM. We’ve been talking about technology in construction for a long time and it’s only over the past four or five years that we have actually started to see what everyone is talking about – the automation of things – and BIM is driving that forward, in no small part by the government directive [for the industry to achieve Level 2 BIM on centrally procured projects by 2016].

‘It’s paying dividends because people have had to take note and improve. It’s easy to talk about these things, but putting them into practice is another matter. Skanska has put its hand in the air and said: “This is our project, we said we can do it, so we’ll put our money where our mouth is.” The industry and the government have set the bar, and we’re just above it as we try to upskill the sector.’

Ultimately, it is BIM’s job to facilitate collaboration between the owner, architect, engineer, contractor and subcontractors. By providing a data-rich picture of the project, stakeholders can work together towards the common goal: a high-quality project delivered on time and on budget. Skanska, it appears, is leading the way.