As the United Kingdom accelerates its transition towards net zero heating, heat pumps have emerged as the primary technology for decarbonising space and water heating. With more than 200 million units already installed globally, the efficiency of these systems is critical; higher performance reduces energy system costs, lowers carbon emissions and alleviates peak strain on the electricity Grid.

However, real-world data reveals a significant ‘performance gap’ between different installations, a challenge that must be addressed to ensure the economic viability of the transition.

The recent study Bridging the efficiency divide: open-source insights into UK heat pump performance gap provides a compelling analysis of this divide, drawing on data from the open-source HeatPumpMonitor.org platform and the UK’s Electrification of Heat (EoH) trial.1 Its findings offer a technical roadmap for designers and installers to narrow the efficiency gap through better design, commissioning and control strategies.

The performance gap in numbers

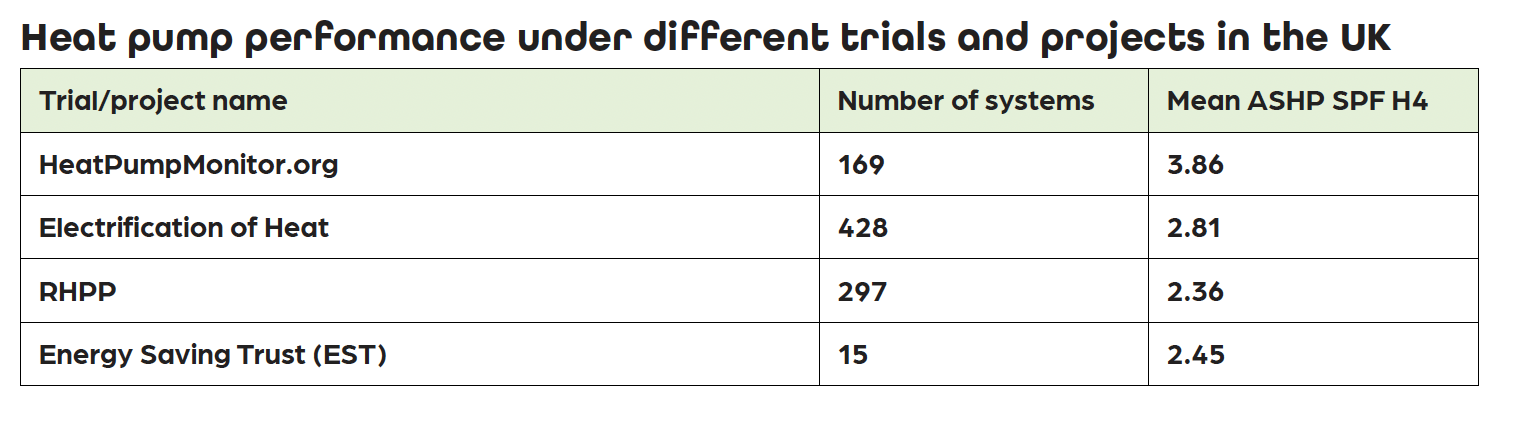

The core of the study lies in the stark contrast between two datasets. Systems monitored on HeatPumpMonitor.org reported a high average seasonal performance factor (SPF) of 3.86 at the H4 boundary (this metric accounts for the efficiency of the entire heating system).

Benchmarking success

HeatPumpMonitor.org is a community-led, open-source initiative, established by the OpenEnergyMonitor community to facilitate the transparent sharing and comparative analysis of real-world heat pump performance.

As of November 2025, the platform had tracked data from 594 systems, with 413 of these using MID-certified meters to provide standardised and trustworthy evidence of efficiency.

The organisation’s primary objective is to define the “state of the art” in system performance, proving that high efficiency is achievable through rigorous system design, installation and commissioning.

Beyond serving as a data repository, it functions as an educational resource for the industry, offering granular insights into how specific heat pump models modulate, cycle and perform under defrost conditions or extreme cold. This empirical evidence allows building services professionals to move beyond theoretical models and optimise real-world calibrations to lower consumer costs and reduce Grid strain.

In contrast, the EoH trial recorded a significantly lower average SPF of 2.81. Earlier trials, such as the Renewable Heat Premium Payment (RHPP) scheme, showed even lower efficiencies, averaging 2.36.

An SPF of 2.8 results in running costs roughly equivalent to a gas boiler. Achieving an SPF of 3.86, however, yields annual cost savings of approximately 26% – around £224 for an average household – demonstrating that technical best practice has tangible economic benefits.

The paper highlights several key factors that contribute to this discrepancy, including suboptimal weather-compensation settings driving high flow temperatures, frequent cycling on room temperature, and extended operation at less efficient compressor modulation levels. Based on these insights, the study presents technical and policy recommendations for improving heat-pump performance.

The thermodynamic driver: flow temperatures

The study identifies that the strongest correlation with high performance (R² 0.55) is the heat output-weighted average difference between flow temperature and outside air temperature. This aligns with Carnot thermodynamic principles: the smaller the temperature lift, the higher the efficiency.

Analysis of the high-performing systems on HeatPumpMonitor.org offers specific benchmarks for design:

- For SPF ≥ 4.0: Systems require an average flow temperature on the coldest day of 36.6°C ± 5.5°C.

- For SPF ~ 3.5: Systems require an average flow temperature on the coldest day of 39.5°C ± 5.5°C.

These figures stand in contrast to traditional ‘rule of thumb’ design flow temperatures of 45°C or 50°C.

Optimising weather compensation

Detailed interrogation of the EoH trial data revealed that suboptimal weather compensation is a primary cause of inefficiency.

A visual inspection of 165 Vaillant AroTherm systems in the trial showed that 55% were operating with weather compensation settings that were too high, causing them to cycle frequently on room thermostats rather than maintain steady-state operation.

In one representative case study (EOH2578), a system frequently ramped up to flow temperatures far higher than necessary, followed by 1.5-hour ‘off’ periods. This ‘stop-start’ cycling at full capacity is significantly less efficient than modulating the compressor to match actual demand.

Dynamic simulations suggest that optimising the weather compensation curve and allowing the system to modulate could increase the coefficient of performance (COP) from 2.86 to 4.61, if the schedule time was moved from 5am to 1.45am to meet the same 19.6°C room temperature between 6.45am and 8.45pm. The changes reduced energy electricity consumption by a third and peak electricity demand was reduced at 6am from 5.1kW to 1.2kW.

Technical recommendations

The sources provide several clear technical levers to improve real-world outcomes:

- Target lower design temperatures: Engineers should aim for design flow temperatures of no more than 40°C, and ideally closer to 37°C, to achieve high-end performance.

- Refine heat-loss calculations: Traditional calculations often overestimate actual heat loss. The sources recommend using more precise methods, such as air-permeability testing and the EN 12831-1:2017 calculation method.

- Prioritise emitter size over capacity reductions: When accurate calculations reveal lower heat losses, designers should lower the design flow temperature rather than reduce the size of the radiators. This allows the existing or planned emitters to provide sufficient heat at a higher efficiency.

- Optimise controls: Careful adjustment of weather compensation is critical. Even in ‘low-disruption’ retrofits, where emitters are not upgraded, optimising these settings can significantly boost performance.

- Minimise setbacks: Large temperature setbacks in heating schedules necessitate higher flow temperatures to recover the heat, which can degrade SPF. Maintaining room temperatures within a narrow range (for example, 18-20°C) is preferable.

Policy and industry standards

The study concludes that current UK policy – which often provides incentives per unit installed rather than being based on performance – does little to encourage high-efficiency outcomes. To bridge the divide, several policy shifts are proposed:

- Standardising onboard monitoring: Integrated monitoring in many heat pumps is currently unreliable for comparison. A common accuracy standard for onboard monitoring would provide a low-cost alternative to third-party metering and facilitate performance guarantees.

- Promote performance guarantees: Policies should consider rewarding above-average real-world performance.

- Enhanced training: Installer accreditation should be updated continuously in light of field-trial evidence, to ensure they are equipped to design for low-temperature operation.

The divide between the 3.86 SPF achievable in well-optimised systems and the 2.81 SPF seen in wider trials represents a missed opportunity for energy saving and Grid stability.

By focusing on low flow temperatures, accurate heat-loss assumptions and rigorous commissioning of weather compensation, installers can ensure that heat pumps deliver on their promise of low carbon, cost-effective heating.

As the study suggests, the performance gap is not an inherent flaw of the technology, but a reflection of how it is currently designed and operated.

References:

1 Rosenow, J., Lea, T. and Boni, G. (2026) ‘Bridging the efficiency divide: open-source insights into UK heat pump performance gap’, Energy and Buildings, 352, 116785.