Examples of low-GWP ASHPs include Weatherite’s R290 heat pump

An analysis of more than 100 air source heat pumps (ASHPs) by Max Fordham has revealed that not all have the same embodied carbon, and that current, generic modelling methods risk unfairly penalising sustainable specifications.

While low global warming potential (GWP) units, such as those using R290, are generally larger and have greater mass, the study found that they often exhibit a lower upfront carbon impact per unit mass compared with equivalents.

This is because the extra mass primarily constitutes lower-carbon body material, rather than high-impact components. Consequently, relying on generic carbon factors significantly overestimates and penalises low-GWP units, underscoring the critical need for assessors to use product-specific data and ensure proxy products are selected carefully to achieve accurate embodied carbon results.

The study also found that few manufacturers offer a full material breakdown of the ASHP units seen. Without this transparency, it is difficult to understand and scrutinise manufacturers’ embodied carbon calculations.

The need for data transparency

Of the ASHPs for which we could obtain embodied carbon data, only a handful offered material breakdown transparency. Material breakdown is a key step in calculating A1 material carbon impacts related to the product and is data that manufacturers have, but do not publish.

The absence of this breakdown makes it difficult to understand and scrutinise embodied carbon calculations completed by manufacturers. Without data transparency, it is impossible to judge which results represent genuine embodied carbon savings or have underreported components.

In analysing the seven material breakdowns we could obtain, there was significant variation in the level of detail provided by manufacturers, even within the same data type.

One key area is electronics, where reporting varied in category and magnitude. Electronic components have an incredibly high embodied carbon impact per kg, so it is important that we report this accurately and consistently.

It was also found that some manufacturers had listed refrigerant as a material component, indicating a lack of understanding of the methodology. There should be more training and guidance provided to manufacturers who complete material breakdowns.

In the move to obtain data for embodied carbon reporting and benchmarking, we must ensure data quality is not overlooked, and strive for data transparency and consistency of reporting.

Publishing product embodied carbon totals may inform averages, but they do not improve understanding of impacts. If manufacturers are making active efforts to reduce embodied carbon emissions, this data should be published to inform best practice.

This work has been initiated by the TM65 verification scheme, which requires manufacturers to publish their calculations for review.

There is an ongoing CIBSE project to collate a centralised MEP embodied carbon database. It is likely that verification and data transparency will form a key part of this structure.

Max Fordham is contributing by sharing our internal product database and lessons learned. We hope this collaboration will lead to a valuable resource in the industry.

Visit: bit.ly/CJEmbVer

This work has been initiated by CIBSE’s TM65 verification scheme, which now requires manufacturers to publish their calculations for review.

Low GWP becoming the norm

ASHPs use refrigerants to transfer heat from external air to a heating medium (typically water). Refrigerants are essential to the operation of this ‘low carbon’ technology, yet there can be significant carbon emissions associated with refrigerant leakage.

The impact of this leakage varies significantly between refrigerant types. Recently, there has been a push from the industry to reduce leakage impacts by moving towards low-GWP refrigerants, such as CO2 (R744) and propane (R290).

Swegon R290 heat pump

Max Fordham has been adopting R290 units on projects, and observed that they are generally larger and of greater mass than units of other refrigerant types. This made us question how the refrigerant might influence ASHP body design and if low-GWP units have greater embodied carbon impacts. So we compiled a database of embodied carbon data, studying more than 100 ASHP Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) and mid-level reports based on the CIBSE TM65 methodology, which estimates embodied carbon when there is no EPD.

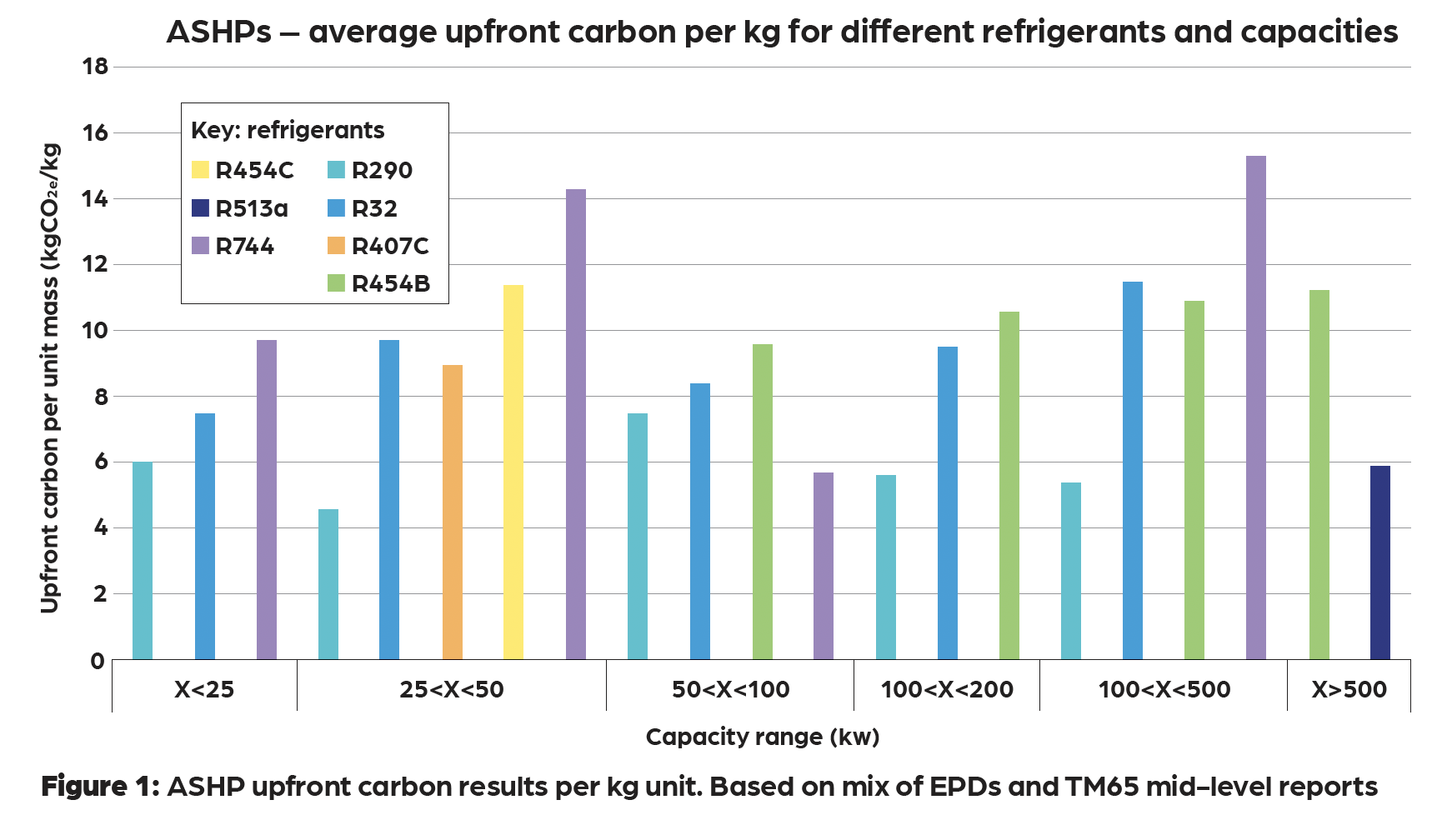

To compare a range of unit sizes, carbon results are typically expressed in relation to a product’s mass. For a comparison of unit material impact, Figure 1 shows upfront carbon (A1-A3) results, which do not include refrigerant leakage or other lifespan impacts. In the study, we found large differences in upfront carbon between ASHPs using different refrigerants.

As with all types of embodied carbon reporting, it is important to note that the underlying material carbon factors (typically given as kgCO2eq/kg material) can differ wildly and may be the cause of lots of variation. Material carbon factors quantify a normalised embodied carbon of a given material. They are used in embodied carbon calculations to easily translate a material mass into an equivalent carbon dioxide impact.

Without public declarations of the carbon factors used, we will always be limited in our investigations into understanding trends.

Figure 1 illustrates a common trend of R290 reporting lower average upfront carbon per unit mass than other refrigerants. It shows consistent, mid-range upfront carbon totals for R32 and R454B, while R744 (CO2) varied quite significantly. There was not a clear trend between units of different capacity ranges.

The most notable observation is that R290 units have significantly lower upfront carbon impact per kg than equivalent ASHPs. While the units are generally higher mass, the embodied carbon does not necessarily increase proportionally. A lower embodied carbon rate indicates that this additional mass is in body material (which is comparatively low embodied carbon), while high-impact components – such as heat exchangers or electronics – are probably similar between units.

Baxi Auriga R290

Additional body material may be related to the increased safety requirements of R290, such as better compartmentalisation and mitigation of spark risks. While total embodied carbon will still generally be higher for R290 units, the difference may not be as significant as feared.

It may also be expected that CO2 units have different material requirements because of higher operating pressures. While this can be seen in Figure 1, there was not enough data to draw a firm conclusion.

The extent to which these results are dictated by inherent refrigerant differences or other industry developments in unit design is unclear. For example, improvements in acoustic performance will probably influence frame/fan design in newer units irrespective of refrigerant type. The data above also did not account for compressor types or performance differences, so the impact of this is also unclear.

Proxy product selection

The lack of product-specific EPDs within MEP equipment means that product substitutions must be made when we model embodied carbon impacts. These ‘proxy products’ are chosen to be suitably similar to the intended product, such that the embodied carbon data is also considered equivalent when scaled for project reporting.

The variation of results in Figure 1 made us question how we model ASHP embodied carbon. Historically, we would model ASHP unit bodies in generic terms and then post-process specific refrigerant leakage impacts. Seeing the variation in upfront carbon rates, however, we realised this would significantly overestimate and penalise low-GWP units.

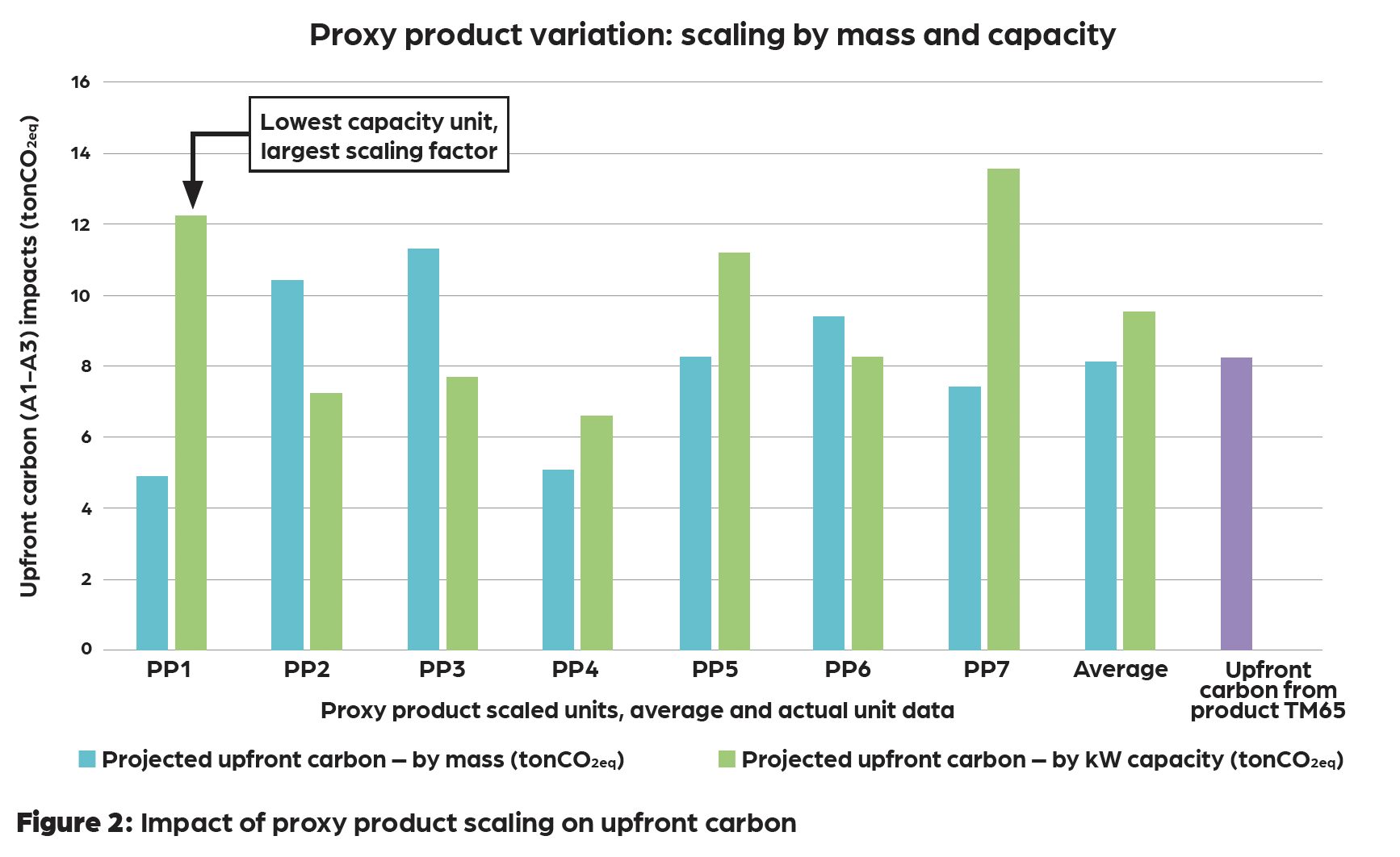

Proxy product selection and scaling can have drastic implications on embodied carbon approximations, irrespective of refrigerant. Given proxy products are scaled, often per kg, any margin of error can be scaled by a factor of thousands.

AquaSnap 61AQ R290 heat pump

Another choice of scaling factor could be per kW output, as this represents a more comparable performance and will typically scale to a factor of hundreds. However, the rated capacity output of a unit will vary by heating vs cooling performance, as well as standard external conditions chosen as a representative output. Both methods are flawed and do not fully capture unit equivalency.

To illustrate the implication of these decisions, several proxy products were chosen to represent a unit with known embodied carbon data. These units were scaled by mass (blue) and capacity (green). Figure 2 shows the variation of projected upfront carbon results when using different proxy products to represent a desired unit (purple). In most cases, there is a notable difference in results when scaled by mass vs capacity, though it is not clear which is most accurate. Note, the lowest capacity unit has some of the greatest variation when scaled to represent a larger unit. Once the proxy products were averaged, the result was much closer to the desired unit (purple). In modelling, we must use a single proxy product rather than an average, but averages can help inform this decision: here, PP6 is sensible.

If proxy products are necessary, selections should be units of the same refrigerant and, ideally, the same capacity range. Assessors should aim to scale the proxy product as little as possible and be wary of using domestic units to represent commercial. It is good practice to undertake sensitivity analyses between data sources and seek advice from MEP engineers to ensure equivalent performance.

After this study, we enhanced our internal modelling processes to incorporate unit type, capacity, and refrigerant sensitivity. Collaboration between our materials and MEP teams has improved modelling accuracy significantly and upskilled both disciplines. Improving the accuracy from product level up gives greater confidence in all levels of modelling, especially optioneering exercises, where the detail of differences can hugely influence project direction.

About the author

Lia Minty is an engineer at Max Fordham