Most organisations are not geared up to nurture the full potential of their neurodiverse workforce

I’ve always known there was something odd, but I had no words for it at the time. I seemed to be able to do the things that other people couldn’t and not do things that everyone else could.’

There is no doubt other neurodiverse engineers would identify with the experiences of Professor Andy Ford, who publicly announced he was dyslexic in 2020 in RAC Magazine.

A CIBSE past-president, and director of research and enterprise at the School of the Built Environment and Architecture at London South Bank University, Ford says he concealed his condition for most of his life, surrounding himself with people who could ‘fill in the gaps’ for the things he found challenging because of his dyslexia.

He says the talents of many neurodiverse engineers are not being realised because they are not being supported in industry, but there are ways in which organisations can help neurodiverse people thrive.

The proportion of dyslexic people in engineering is expected to be much higher than the 10-15% of the general UK population with the condition

Form filling, for example, can be extremely difficult for people with autism or dyslexia, so membership organisations should do more to make their entry processes easier.

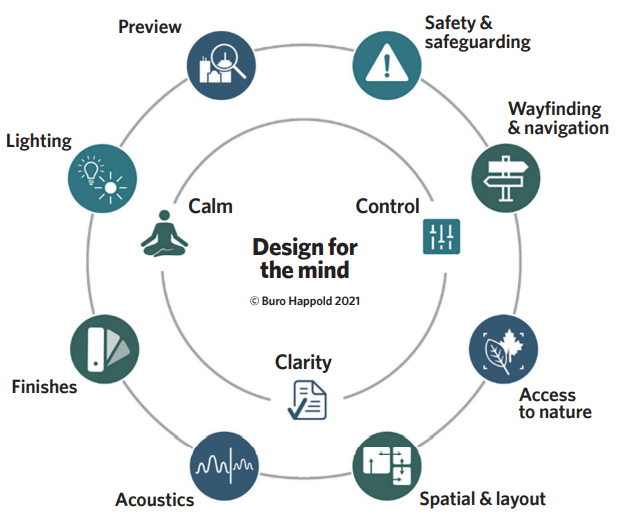

Another way to help is by designing spaces that are sensitive to people’s different neurological states. A new design standard – PAS 6463 – due out in the spring, aims to do exactly that.

The author is Jean Hewitt, senior inclusive design consultant in the inclusive design team at Buro Happold. ‘An environment that is easy to understand – with sensible acoustics, lighting and wayfinding – can be calming for individuals and doesn’t contribute to anxiety,’ she says.

Strength in neurodiversity

The term neurodiversity was coined in the late 1990s by autistic sociologist Judy Singer. According to Singer, it refers to the concept that certain developmental disorders – such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, dyslexia and dyspraxia – are normal variations in the brain, and people with these features also have particular strengths.

Stephen Gill, a consultant, and founder of the Institute of Refrigeration’s Dyslexia in Engineering Day campaign, is himself dyslexic. He says: ‘Everyone is different and, within that neurodiversity, there are people who learn differently – and they are neurodivergent or neurodiverse.’

Gill says some associated strengths of dyslexia – such as creativity, problem solving and thinking outside the box – are relevant to engineering. As such, he says the proportion of dyslexic people in engineering is expected to be much higher than the estimated 10-15% of the general UK population with the condition. So, it is increasingly important to ensure that the building engineering sector embraces the challenges and opportunities posed by neurodiversity.

Organisations, employers and managers must learn to understand the benefits that neurodiverse individuals can bring to the industry, as well as the challenges they face. ‘If we are to succeed as a workplace, as an Institution, and as a profession, we need to get the best out of everyone,’ Gill says.

Unfortunately, at the moment, organisations are not geared up for it, he adds, and ‘the majority of neurodiverse individuals keep it hidden because they are worried about exposing themselves and their weaknesses’.

The challenges

During his childhood, Ford recalls that people with dyslexia were called ‘slow’ because of a lack of awareness of the condition. Even today, he adds, ‘the challenges don’t go away; you overcome them, but they don’t disappear – your brain is what your brain is’.

He says certain aspects of university, such as exams, were a struggle because ‘there was no allowance for dyslexia and I ended up failing more regularly than I wanted to. I can’t claim to have a great degree, and I only just scraped through the second time in my A Levels. I’m lucky because many people give up at this point.’

Despite struggling with reading and writing – and form filling, which was ‘almost impossible’ – Ford found support in people around him who were good at the things he wasn’t.

Like Ford – who, at the age of 30, established his own consulting practice, Fulcrum Consulting (later bought by Mott MacDonald) – many neurodiverse engineers go down the self-employed or entrepreneurial routes, says Gill, because the way to leadership through college, management, and management school is not open to them.

In an informal survey of engineers, via LinkedIn, Gill found that 713 identified as dyslexic and, of those, 98% said they wouldn’t tell their employers they have it. More than half didn’t belong to an engineering association because they felt they wouldn’t fit in.

The majority of neurodiverse engineers keep it hidden because they are worried about exposing themselves and their weaknesses

‘Coming out’ as neurodivergent can set people back in their careers, says Gill: ‘They may not be sacked, but they may not get a career promotion. Dyslexia is a career killer.’

He cites a former mentee, who was a ‘rising star’, but who struggled during the first stages of management because of her dyslexia. ‘I suggested to make an appointment with HR and they would put everything in place – it turned out to be the worst advice I had ever given. They said “perhaps you should go into your previous role”, so she resigned. That was a wake-up call for me and why I [started the Dyslexia in Engineering Day] campaign.’

Gill, who has been liaising with various professional organisations, says it’s important for membership bodies to work together to ensure their registration processes are accessible for neurodivergent people.

‘Do they really have to fill out forms these days? There are other ways,’ he says. ‘They need a review of their membership processes, and they need a creative brainstorming committee.’

CIBSE’s approach

In his experience as an academic in Dublin, CIBSE President Kevin Kelly says he witnessed many dyslexic students graduate with first-class honours degrees because the modern educational environment ‘enabled people with dyslexia to come through more easily’. There were examination methods that allowed people to record answers on a voice recorder rather than in written form if they preferred, and papers could be read out to people.

He acknowledges that, as a professional body, CIBSE could be subconsciously excluding certain groups as a result of its entry methods. To attract more people into engineering, Kelly admits CIBSE should be ‘more diverse in our message’.

‘We’re in such a fast-changing climate, with global challenges around zero energy buildings, that we need as diverse a set of minds addressing the problems as possible,’ he says. ‘That difference is what helps to solve the most complicated problems in our world.’

CIBSE is starting to weed out the ‘unconscious bias’ of asking people to fill in forms, he adds – for example, the board and council nominations procedure has been improved, and neurodivergent individuals can now send in videos rather than fill out forms. ‘If we can do better with our procedures, please tell us how, because we want to do it better,’ Kelly says.

Guidance

About 70% of people with autism will have hypersensitivity to certain parts of the environment, says Jean Hewitt. ‘There are so many other conditions as well, and the thing they often have in common is a sensitivity to noise, light, patterns and colours, and touch. So, acoustics and lighting are incredibly important.’

Hewitt is technical author of PAS 6463 Design for the mind – neurodiversity and the built environment, which went out for public consultation in November. The final version will be released by the British Standards Institution (BSI) in spring (see panel, ‘Design for the mind’).

Feeling like you don’t belong is a daily struggle for many neurodiverse individuals, whose talents are being overlooked because of a lack of understanding and support

The guidance is aimed at designers, developers, architects, surveyors, inclusive design and access consultants, occupational therapists and building managers.

Failing to design for neurodiversity could put employees off coming back to the office, says Hewitt, adding. ‘We need a diverse workforce and, if we don’t fix it, people will home work. This would be sad, because we need that diverse community in our buildings.

‘The majority of these people are very capable and it’s wrong that our workplaces, social places and even living accommodation haven’t thought beyond the neurotypical.’

Inclusivity

Feeling like you don’t belong is a daily struggle for many neurodiverse individuals, whose talents and skills are being overlooked because of a lack of understanding and institutional support. Often, as Gill points out, the modifications or adjustments needed ‘are very minor, but can make a huge difference’.

With the challenges posed by climate change and reaching net zero, we need minds that think differently and creatively. ‘We need to attract loads of other people, and we’re not going to be able to do it the way it’s been done before,’ says Ford. ‘There is huge benefit in building an organisation that has people with different skill sets who can talk to each other freely to develop ideas.’

Building services engineers alter buildings’ heating, ventilation, lighting and acoustics, so designing with neurodiversity in mind is surely an extension of the work we already do.

Designing for the mind

PAS 6463 Design for the mind – neurodiversity and the built environment, which will be reviewed after two years, focuses on control and clarity of space. Clarity encompasses the lighting, acoustics, sightlines – everything logical, says technical author Jean Hewitt, and control is the adjustment of lighting or having the choice to sit somewhere calmer and quieter.

‘A lot of people will experience a sensory overload – some people shut down and become non-verbal; it’s a bombardment of noise, light and smell. It’s such a sensitive experience that the brain can’t cope with it,’ she says.

As well as practical advice about fittings and their design, the document informs about the quality of light, suggesting to steer clear of fluorescent lights in favour of LEDs. However, LED lights can have a flicker if not appropriately designed, so guidance around this – and the colour temperature of lighting – is also included.

‘A lot of people find the blue and white light disturbing, so it’s about giving people a choice, such as a desk lamp and changing the colour tone of the lighting. Warmer lighting tends to be more calming than blue light, which tends to wake us up,’ Hewitt says.

In terms of wayfinding, the guide refers to designing logical, clear spaces with good sightlines, ‘things that you would normally think of as being good design’, says Hewitt, who says the publicly available specification is likely to get absorbed into a British Standard and become a code of practice.

‘Hopefully, people will start reading it, applying it and testing it, and coming back and helping BSI and others to evaluate it,’ she adds.