This year marks the 40th anniversary of the creation of CIBSE, when the Institution of Heating and Ventilating Engineers (IHVE) amalgamated with the Illuminating Engineering Society.

As now, one of the most pressing issues facing the new institution was the UK’s relationship with Europe. However, unlike today, the debate was around the challenges and opportunities of Britain’s closer ties with Europe – ‘Brenter’ rather than Brexit – following the 1975 referendum decision to remain in the European Economic Community.

In his 1976 presidential address, Alec Loten, IHVE President, spoke of the standardisation of construction benchmarks across Europe, and of the benefits of working with engineers from overseas. He said: ‘In many ways, we can learn from the expertise, knowledge and work of foreign engineers and… we should do so readily, without shame and to our ultimate advantage.’ How times have changed.

Britain in 1976 was a time of miners’ strikes, oil shortages and severe drought. Punk – not Bieber – was in the music charts, and Charlie’s Angels graced the TV screens. Despite the huge social, economic and environmental shifts since, some things haven’t changed. Hinkley Point B came online four decades ago and, last month, Prime Minister Theresa May announced its replacement – Hinkley Point C.

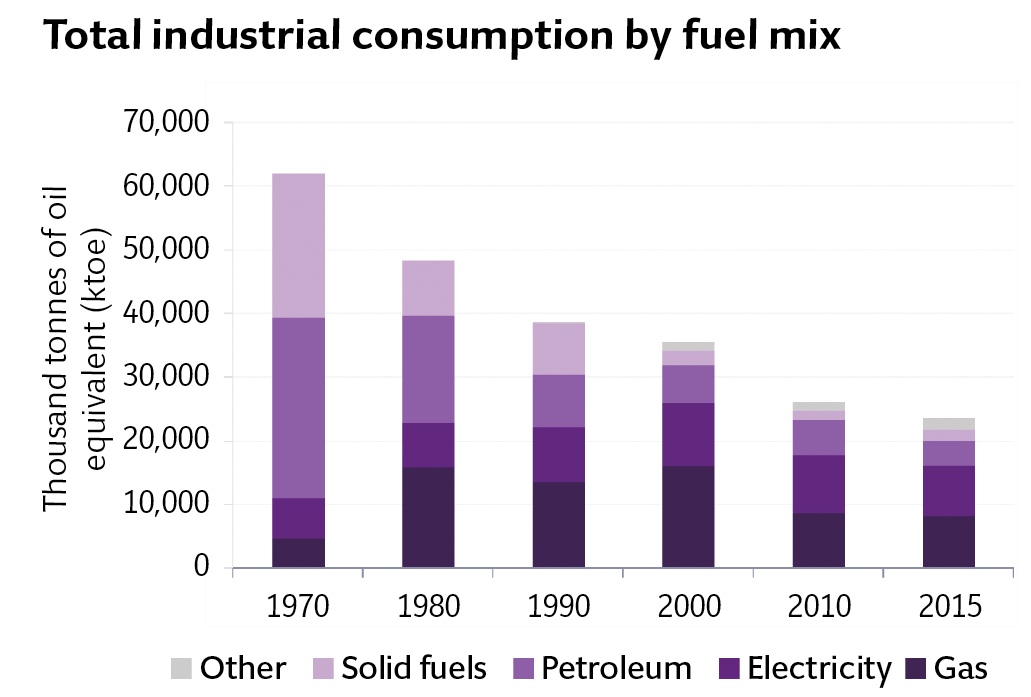

Although nuclear power had been established by the 1970s, the UK still relied on oil and coal as its main fuel sources, followed later by gas after the discoveries in the North Sea (see fuel mix graph below).

The changing mix of fuel sources on a primary energy basis, and total consumption. Source: BEIS ECUK table 1.10

In 1976, the current CIBSE President, John Field, was designing the nuclear power reactor for Sizewell B, which was only connected to the grid 20 years later. ‘The nuclear industry was not looking very promising, and that’s part of the reason I left to work in renewables,’ says Field. ‘The main problem at the time was scarcity of supply, in terms of fuel, and where it was going to come from.’

This feature will explore the changes to the UK’s energy landscape since 1976 – as coal and oil gave way to gas – as well as developments to the way in which we heat and power our buildings. It will also discuss the socio-economic factors that led to the role of the building services engineer evolving.

Uncertain times

In the 1970s, Loten’s words were set against a backdrop of significant economic and political changes in the UK. The oil-price shock of 1973 – caused by Arab oil producers imposing an embargo as a punishment for the West’s support of Israel in the Yom Kippur war against Egypt – and subsequent coal miners’ strikes in 1974, led to blackouts across Britain.

To conserve electricity, the Conservative government introduced a three-day week from 1 January until 7 March 1974, during which commercial users of electricity were limited to three specified consecutive days’ consumption each week. ‘There was a high degree of uncertainty about what the future held – not just for the construction industry, but for society as a whole,’ says Doug Oughton, who was an engineer at Oscar Faber & Partners (now Aecom).

A picket questions a driver leaving West Drayton National Coal Board Depot at the height of the miners’ strike

‘The three-day working week threw a spotlight on energy consumption and use.

‘At that time, it became quite a resonant feature in our approach to design and operation of buildings. It probably also started the coming together of architects and building services engineers, who were beginning to think of buildings as an entity, and combined their designs so they could perform in terms of comfort and energy use.’

Ant Wilson, who was working on a water interceptor on the River Avon in 1976, agrees: ‘In parallel with today, one of our biggest concerns was security of supply and making sure the power didn’t go out.’

After the so-called ‘winter of discontent’ in 1978-79, the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher took on the mining unions. This – plus the deregulation of the energy industry and discovery of gas in the North Sea – brought an end to the widespread blackouts that had plagued Britain.

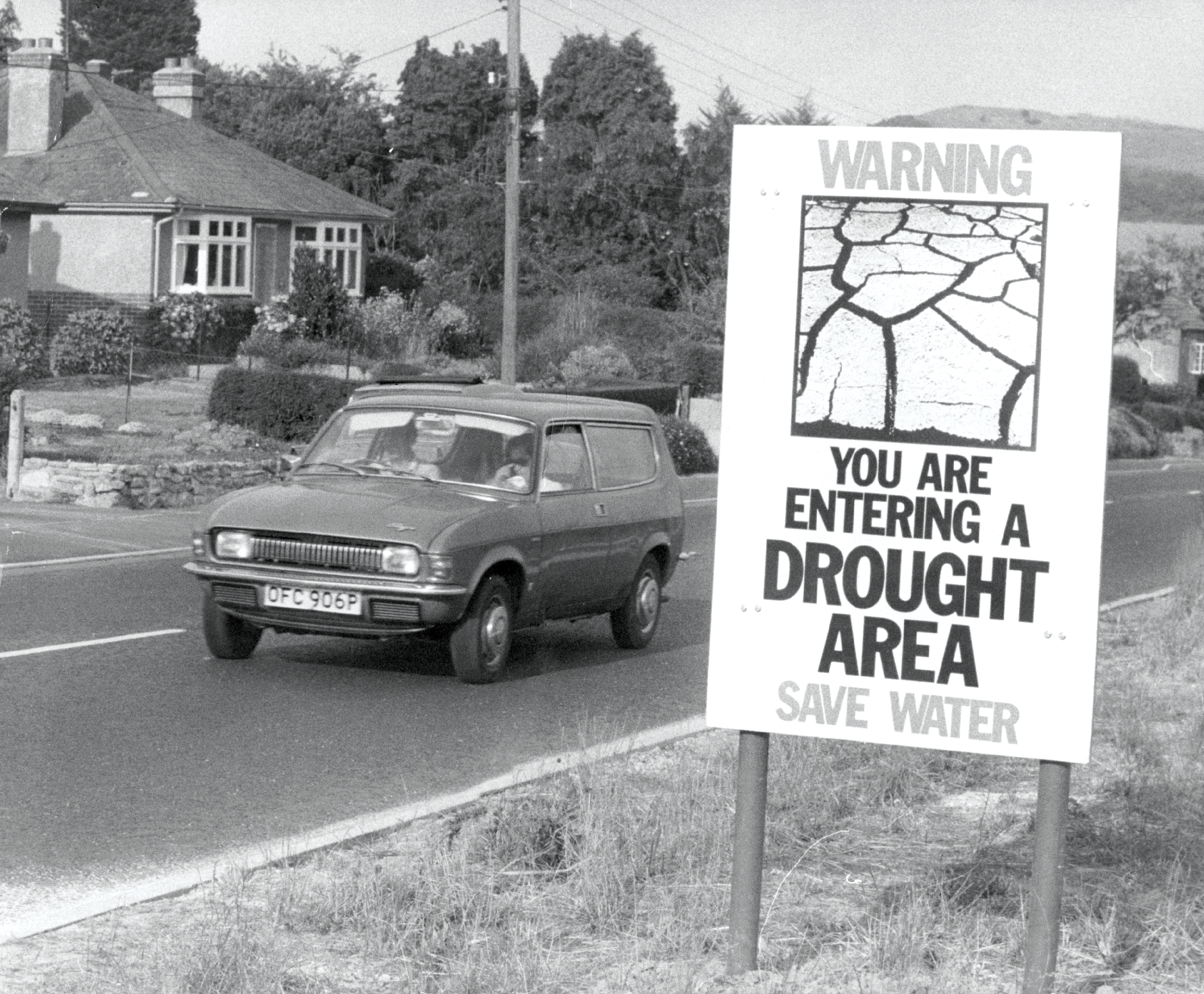

Water conservation was also high on the agenda in the 1970s, because – in the summer of 1976 – Britain experienced an extreme heatwave and severe drought. Heathrow recorded 16 consecutive days – from 23 June to 8 July – when the temperature exceeded 30°C and, for 15 consecutive days, it reached 32.2°C somewhere in England.

Anglian Water Authority, among others, announced a hosepipe ban in an effort to conserve the water in its reservoirs, which were losing nearly six million gallons a day through evaporation.

A public information notice warning about the drought, erected by the road in the Bridport area of Dorset in 1976

Air conditioning was still in its infancy. According to newspaper reports, only Debenhams department store in Southampton had had it installed – at considerable cost, eight months earlier – but it was too expensive to switch on. An hour’s use would exert the same strain on the electricity tariff as maximum demand for an entire month, costing the then unimaginably extravagant sum of £2,500.

So prolonged was the hot spell in 1976 that CIBSE’s TM49 Design Summer Years for London uses the year as one of its extreme weather files.

Industry changes

In the mid-1950s, nearly all the work in the building services industry was carried out by design and build contractors, who undertook both project design and installation.

Graham Manly, who was contracts director at family firm A G Manly and Co, says consultants started to come on the scene in the 1960s. ‘But the majority of these consulting engineers had come from – and been trained by – contractor apprenticeships.’

Oughton, who was also contractor-apprenticed, adds: ‘It was a very good way of training people; contractors had access to sites and workshops, and carried out both installation and commissioning.’

By the 1970s, however, consulting engineers were becoming dominant, with almost the entire membership of the institution coming from the design fraternity.

Manly says: ‘The way in which people worked together attracted me to the industry. Because many consultants had been trained by contractors, the relationship between the two was very good and, if problems arose, they were sorted by mutual agreement.’ This cohesive environment only started to deteriorate during the next decade, he adds.

Technology in 1976

CIBSE Journal technical editor, Tim Dwyer, reflects on technology in 1976

Dwyer says the TI-30, with an LED display, was the ‘real beast’ of the time, which was craved by all

Geeky early adopters, confined to the often unpleasantly warm computer room – or connected through a very limited, and probably proprietary, network – used dedicated terminals. Text-based, green-screened cathode ray tube interfaces, with expensive purpose-made keyboards or punch cards, fed information into calculation software packages such as ENDSOP in coding languages such as Fortran.

Modelling was still a physical art, confined to architects’ offices and research centres keen to explore practical fluid dynamics. Output was printed on dot-matrix printers, with the gifted users able to coax technical symbols and crude ‘graphics’ from the clattering devices. The mouse was confined to the few pioneering users of the Xerox Alto computer, while the ‘Arpanet’ was limited to specialist users – and the now universal @ sign was a wasted typewriter key to most engineers. The ‘personal computer’ was just appearing as the microprocessor became a mass-market commodity, and the first commercially successful operating system for microcomputers, CP/M, also appeared, soon to be eclipsed by Microsoft’s MS-DOS. It was also in 1976 that the Apple computer was born.

The 1980s was a period of a major uplift in construction, especially in the commercial sector. But with this boom, Manly says, came confrontation within the industry between engineers and contractors: ‘There was a new breed of designers who had not come from a contracting background, so had no practical experience – and their designs just weren’t up to it. Many projects ended up in the courts because jobs didn’t get finished on time or within budget.’

Another industry pressure came in the form of a supply and demand imbalance. Unlike in the 70s, when half of all construction projects were publicly funded, the 1980s brought an onslaught of government cutbacks to capital investment. The situation was compounded by the 1983 recession, which forced firms to lay off staff. Oughton says: ‘People took up completely different jobs, so – when the industry picked up again in 1985 – the pool we were drawing from had significantly reduced.’

The skills shortage was a recurring theme throughout the decades, adds Oughton, who served on the CIBSE careers panel for more than 10 years. ‘One of the biggest challenges for the Institution has always been promoting building services as a career to young people.’

Evolution of engineering jobs

IT and technology, and a focus on sustainability, have transformed the roles available to building services engineers, says Richard Gelder, Hays building services director.

Typical building services roles in 1976:

- Drawing office manager

- Draughtsman

- M&E superintendent/chargehand

- Borough engineer

- Design technician

Typical building services roles in 2016:

- Digital engineer

- Energy manager

- IES modeller

- Revit/BIM technician

But, as the 1990s approached, London’s skyline was again peppered with towering cranes. ‘People couldn’t turn out the work fast enough; jobs got behind and corners were cut,’ says Manly. ‘This led to client dissatisfaction, complaints and contract clauses being invoked.’ The reduced workforce meant organisations were employing anybody, so compliance and professionalism suffered.

After a second recession in 1993 – which levelled off the supply/demand imbalance – the next decade was stable. Most people ‘could plan for next year’, says Manly.

Energy mix

In the early 1970s, most major projects used heavy fuel oil – a thick, tar-like substance that was cheap and unrefined, and which replaced the 1920s coal-fired boilers. ‘Coal was dirty, and required a lot of manual labour to shift and stoke it day and night, so it was being replaced with heavy oil in the 60s,’ says Manly.

After the coal miners’ strikes, North Sea gas was discovered. ‘The 70s saw the growth of gas,’ says Manly. ‘Plant – including the boiler I was working on for the 20,000-bed Epsom Hospital, serving five mental health clinics – was being converted from heavy fuel oil to dual fuel [light oil and gas].’ (See graph, below).

The general fall in consumption reflects the shift away from heavy industry to more energy-light industries. Source: BEIS ECUK table 4.01

Oughton adds: ‘Gas had considerable advantages in terms of lower emissions, flexibility, and less stringent requirements for chimney design. But it didn’t provide a reserve supply so, quite often, dual fuel boilers that ran on gas with oil as backup were installed.

‘Over time, the need for reserve oil was reduced, and gas became the primary supply fuel because it was seen to be a reliable source.’

Between the late 1950s and mid-1970s, district heating was a popular system for many projects. Hot water was piped from boiler houses – running on heavy fuel oil – to each block of flats. But a lack of monitoring and control, as well as pipe corrosion and leaks, moved the focus away from district heating.

‘With the advent of gas came a shift from central generation of heat to individual gas boilers for every flat,’ says Manly.

Efficiency

In the 70s, no-one was thinking about energy efficiency across the board. ‘Fuel choice was mostly based on cost – that is, what’s cheapest – and how easy it was to manage,’ says Manly, who adds that there was a tendency to ‘over design’. ‘You designed by working out what the demand was and added 10-20% to it just to be sure. You never wanted anything to be too small.’

In the era of property indemnity insurance, you covered yourself by ‘adding on’, says Manly. ‘No-one considered the effect on equipment performance or energy use, even though – throughout most of its life – plant was working at half speed.’

However, there has been a gradual shift towards energy efficiency, which took off during the early part of the new millennium and in the 2006 revision of the Building Regulations. ‘It has taken 15 years for it to become the norm,’ says Manly.

The merger

By Royal Charter, the Institution of Heating and Ventilating Engineers and the Illuminating Engineering Society were amalgamated in 1976, to form the Chartered Institution of Building Services (the word ‘Engineers’ was added in 1985). This was the first use of the term ‘building services’, after a realisation that the industry was doing more than just heating and ventilating.

CIBSE: What next?

CIBSE is committed to continue developing, maintaining and sharing knowledge about building engineering to support its members and to champion building performance. This commitment is set out in its 2020 vision statement, soon to be published.

CIBSE will continue to champion the contribution to building performance that its members make, promoting their high standards and professionalism. The vision also recognises the value of strengthening partnerships and growing membership worldwide, particularly while the UK is redefining its links and business relationships globally.

Building performance continues to be a priority, with CIBSE leading the drive to improve the performance of our built environment through a whole life-cycle building approach. Knowledge remains key to CIBSE’s work as we continue to provide best practice guidance to improve building performance. We will also further develop our Knowledge Portal, aiming to launch an update within the next three years.

Digital processes will be a key area of CIBSE’s work, in terms of looking at how it runs its own operations, as well as supporting industry – and member – adoption of digital processes and technologies.

CIBSE looks to support the property and built environment sectors – and its members – by developing resources that deliver comfortable, valuable and sustainable buildings.

According to Mike Simpson, global application lead at Philips Lighting, a strong driver for the merger was the Property Services Agency, which looked after government property. ‘There was a big push for the building services profession to become chartered and gain a level of professional recognition – but its scope was not wide enough. So the IHVE and IES merged,’ he says.

At that time, independent lighting designers did not exist, Simpson adds. There were manufacturers – who did a lot of the design – and electrical engineers, who did the calculations. ‘Architect Derek Phillips pioneered the discipline of independent lighting consultancy in the UK when he started his own lighting design practice in 1958. Now, there are many hundreds of people in the UK – and around the world – solely from a lighting background,’ says Simpson.

‘Somewhere down the line, the attitude towards lighting changed and it became important enough to become a specialised sector. With the advent of LED technology, we are getting a crossover between the engineering, entertainment and architecture sectors, sharing knowledge and experience.’

Rules Britannia

A selection of regulations introduced in the UK from 1976 to 2016

1976 Energy Act

1978 Nuclear Safeguards and Electricity (Finance) Act and Energy Conservation Demonstration Projects Scheme

1981 Energy Conservation Act

1983 Asbestos (Licensing) Regulations

1984 Building Act incl functional performance standards (Approved Documents)

1985 Initial Approved Docs to Building Regs, Rio Earth Convention – Article 21

1987 Montreal Protocol – banned chlorofluorocarbons in aerosols and fridges

1987 Brundtland report Our common future

1988 Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) Regulations

1989 Noise at Work Regulations

1989 Electricity at Work Regulations

1992 Earth Summit in Rio (Agenda 21)

1992 Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations – suite of regulations

1994 Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 1

1995 Sizewell B nuclear power station goes critical

1996 Construction (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations

1997 Kyoto Protocol (came into effect in 2005)

1998 Gas Safety (Installation and Use) Regulations

2000 UK Emissions Trading Scheme (until 2006)

2002 Building Regulations update (Part L Domestic and Non-Domestic)

2003 EPBD adopted

2003 Building (Scotland) Act

2006 Climate Change and Sustainable Energy Act

2006 Building Regulations major update – SBEM and SAP inclusion

2006 F-Gas Regulation 22

2006 Code for Sustainable Homes

2007 Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2007 version

2008 UK Climate Change Act (put Kyoto agreement into law – 80% reduction in CO2 by 2050 compared with 1990)

2009 UK Low Carbon Transition Plan

2010 Building Regulations update

2011 Energy Act, basis for Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards

2012 SAP

2013 Green Deal

2013 Building Regulations update (England)

2014 Building Regulations update (Wales)

2015 Building Regulations update (Scotland)

2015 Paris COP 21 Agreement

2016 Fifth Carbon Budget 2028-2032 adopted

After the merger, Oughton says the institution became more welcoming towards its members. ‘The Young Engineers Network is a good example of how it has become less elitist and more open to the young members and those who have come through the associate grade.

‘Other CIBSE societies – such as Façade Engineering – have got a wide membership and are not dominated by building services engineers. The fact that CIBSE has opened up the work of the Institution to a wider group only benefits its members.’

Oughten adds: ‘There has been recognition across the board of the importance of having a good environment for people – not just in terms of temperature and humidity, but also by taking into account the whole building design and its facilities to provide comfort and good air quality.

When I joined the lighting profession, the Illuminating Engineering Society was merging with IHVE to form CIBSE, and the role of the independent lighting designer hardly existed. The 1974 energy crisis focused minds on creating low-energy light sources and, in 1979, the first compact fluorescent lamp emerged to replace the tungsten one. However, it would take another 30 years – and changes in legislation – for it to become the lamp of choice. Throughout the 80s and 90s, new light sources would shave small percentages off energy use. However, the big step forward came in the 2000s, with the introduction of the LED, which has revolutionised lighting. With the current focus on climate change, lighting can make a big contribution to reducing emissions and, with low-power LED, we can bring electric light to those who have had to rely on kerosene lamps. The lighting designer is now a recognised professional and part of many design teams.Progress in lighting

Global application lead at Philips Lighting, Mike Simpson, explains the developments in lighting over the past 40 years

‘Engineers now need to have a broader skill set – drawing on knowledge from many different sectors – to look at projects holistically and deliver great places for people.’

Despite the UK’s vote to leave the European Union, engineers still need the international skills pool, says Field, who believes much of what Loten said in 1976 still rings true today. ‘We must engage with Europe, the Middle East and America, and streamline our way of working with other nations because, if we do not, the industry will be generalised – it will become Uberised and Amazonised,’ he says.

‘We need to be a part of the social media and blog-related way of working, and do it globally. It’s a fantastic opportunity to make real changes to the industry, but we have to do that cooperatively with international colleagues.’