The unmistakable structure of Battersea Power Station is finally back in use and open to the public

Battersea Power Station has finally opened its doors to the public for the first time in history. In the four decades that have elapsed since the power station ceased generating power numerous attempts at developing the site have failed.

The iconic landmark is Grade II* listed, which means the building had to be preserved in its redevelopment. ‘The biggest challenges in terms of MEP were in maximising the net lettable areas and ensuring compliance with the building’s Grade II* listing requirements,’ says Simon James, associate director at ChapmanBDSP.

The building services design also had to take account of the fact that the power station was built in two halves, decades apart. Designed by architect, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, who also designed the red telephone box, Battersea A was completed and opened in 1933, with one turbine hall and two slender chimneys.

It was not until 1955, when the eastern half of the building, Battersea B, was completed that the building acquired its familiar four-chimney profile. The chimneys were needed to disperse the flue gases from the power station’s pulverised coal-fuelled boilers, which generated the steam that spun its giant turbines to supply a fifth of London’s electricity.

The last of the building's four chimneys was completed in 1955

Post-industrial plans

Over the years, Battersea Power Station became an instantly recognisable feature of the London skyline, and starred on the cover of Pink Floyd’s 1977 album Animals, for which it was photographed with the band’s inflatable pig flying between its chimneys.

With operating costs increasing, however, and output falling with age, Battersea A closed in 1975, and Battersea B was decommissioned in 1983. The challenge then was what to do with this giant, brick-built landmark in post-industrial Britain.

The atrium lets daylight seep onto the floorplates

A series of failed proposals for the 42-acre site followed the decommissioning of the power station. These included: Alton Towers-owner John Broome’s plans to turn the power station into a theme park; a proposal for it to become the permanent home of Canadian entertainment company Cirque du Soleil; plans to turn it into a public park; and even a proposal to turn it into a football stadium to become the new home of Chelsea FC.

However, in 2012 a consortium of Malaysian companies bought the derelict site to turn the power station and its surrounding 42-acre site into a mixed-use development incorporating residential, retail, office and leisure.

Phasing in change

In 2013, architect WilkinsonEyre and engineers ChapmanBDSP were appointed to restore and repurpose the power station structure under Phase 2 of the site’s redevelopment.

Phase 1, Circus West Village – designed by SimpsonHaugh and De Rijke Marsh Morgan – was completed in 2017 and is now home to more than 2,000 people.

Phase 3, Prospect Place and Electric Boulevard, a new pedestrianised high street, is under construction, with more residential apartments, designed by Gehry Partners and Foster + Partners, as well as new retail space and a hotel, due to open shortly.

Two floors of retail space are accommodated in what was the old boiler house

It is Phase 2, the repurposing of the power station, that is key to the scheme’s success. At the heart of WilkinsonEyre’s design is the central Boiler House, which now accommodates three floors of retail and leisure. On the third floor are two cinema screens, an events space and offices for flexible working. Floors five to 10 also accommodate 46,000m2 offices.

Flanking the main power station walls, to the east and west, are the two giant turbine halls. These are now home to three floors of shops, restaurants and unique event spaces. Adjacent to the turbine halls are the meticulously restored original control rooms, and flanking each of the turbine halls are the former switch houses, which contain more residential apartments. Visitors are able to board a glass lift, Lift 109, to take them to the top of the north-west chimney to enjoy views of London, 109m above sea level.

Battersea ceased generating power in 1983

Pitch and plant

The giant double-height plantroom takes up almost the entire fourth floor of the repurposed power station. ‘It’s probably bigger than a football pitch,’ says James.

It is sandwiched between floors in the centre of the building for sound commercial reasons; it kept the ventilation ducts to a manageable size, rather than having to deal with huge ducts dropping down from roof-top air handling units (AHUs). It also had the benefit of freeing the roof from building services plant, creating space for more housing.

“The plantroom is sandwiched between floors in the centre of the building for sound commercial reasons – it helped maximise the lettable area

‘Putting the plantroom in the middle helped maximise the lettable area because smaller ducts go up and down from it, rather than having large ductwork dropping down the building from the roof,’ explains James.

The plantroom accommodates more than 25 AHUs. Ventilation intake louvres are located in the wall on the western side of the plant floor, while the exhaust louvres are concealed in rooftop gardens above the turbine hall, to the east of the plantroom. Ductwork and piped services are distributed via risers concealed in the rectangular wash towers that form the base of each of the four chimneys and in four new access cores constructed in the centre of the building to accommodate lifts and stairs.

A chimney-potted history of Battersea

- The power station was conceived in 1927 by the London Power Company, to meet the capital’s demand for electricity.

- It was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, the architect who designed Liverpool’s Anglican cathedral, Bankside Power Station (now the Tate Modern) and the iconic red telephone box.

- The power station was built in two halves; initially, the western half of the power station was built, along with the SW and NW chimneys. This started generating electricity in 1933. The second half came into service in 1944, at which time a third chimney was completed, giving the building the moniker ‘the 3-pin plug’.

- The power station survived the Blitz, possibly because the plumes of white vapour from the chimneys provided the Luftwaffe with a navigational landmark.

- The final chimney was added in 1955, when Scott’s four-chimney design was finally realised.

- At its peak, the power station’s total generating capacity was 509MW.

- The station ceased generating electricity in 1983.

James says it was a challenge coordinating the various plant and pipework with the new supporting structure that now fills the space. Coordination was helped by the project being designed in BIM. At its peak, ChapmanBDSP had a team of 25 BIM operators working on the scheme.

‘A major challenge with this project is that there is no repetition in terms of risers and floor plates; everything is a bespoke design to accommodate the listed structure,’ he explains.

Down in the basement

Heating and cooling for the entire scheme is provided by a new energy centre located in the building’s basement. It was designed by Vital Energi and is currently being run by Equans.

Turbine hall A’s art deco interior with fluted pilasters and creamy tiles

The energy centre includes two 2MWe gas combined heat and power (CHP) engines, one 3.3MWe gas CHP engine and three 10MW gas-fired boilers, plus seven 60m3 thermal stores and six 4MW chillers. Flues from the boilers and CHP engines use the power station’s north-east and south-west chimneys.

Thermal mass, a small amount of solar gain and some beneficial heat from the retail units will ensure visitors remain comfortable in winter

James says ChapmanBDSP worked with Vital Energi to provide it with estimated energy loads for Phase 2 of the project: ‘We designed the networks that distribute the LTHW [low temperature hot water] and chilled water from it using efficient variable volume systems.’

Alongside the energy centre, the basement is home to the building’s 19 electrical substations. Rather than incorporate standby generators, ChapmanBDSP has saved floor space by bringing in two separate electrical supplies. The project’s 14MW load is supplied by two 7MW supplies taken from the Stewarts Road substation.

ChapmanBDSP’s scheme also eliminates the need for heating and cooling plant to serve the two retail malls that now occupy the turbine halls, which flank the main Boiler House building.

Luxury residential 'Sky Villas' are accessed via a glass lift at the base of one of the chimneys

Styling it out

The interiors of the two halls reflect their different ages: Turbine Hall A has an art deco interior with fluted pilasters and creamy tiles; Turbine Hall B was built after World War II and has a more utilitarian feel. Both turbine halls have the outlines of the generators that once filled the space with noise and movement picked into the floor finish.

‘We were able to thermally model the two turbine halls to demonstrate to the client that the thermal comfort aligned with CIBSE guidance, which saves on plant cost and energy use,’ says James.

Thermal mass, a small amount of solar gain and some beneficial heat from the retail units will ensure visitors remain comfortable in winter.

Both turbine halls incorporate smoke-extract fans at high level to pull smoke out in the event of a fire. These provide yet another example of ChapmanBDSP’s approach to delivering value on the project.

Rather than install additional ventilation plant on the roof, ChapmanBDSP has used the smoke-extract fans to increase ventilation rates, by helping pull air in through the main doors and exhausting it through the roof.

‘Because the Building Regulations call for fresh air to be supplied to the turbine halls, we have agreed with building control that we will use CO2 sensors to run the smoke-extract fans at low volume in the unlikely event that there are so many people in the turbine halls that CO2 levels rise significantly,’ says James.

Cool control

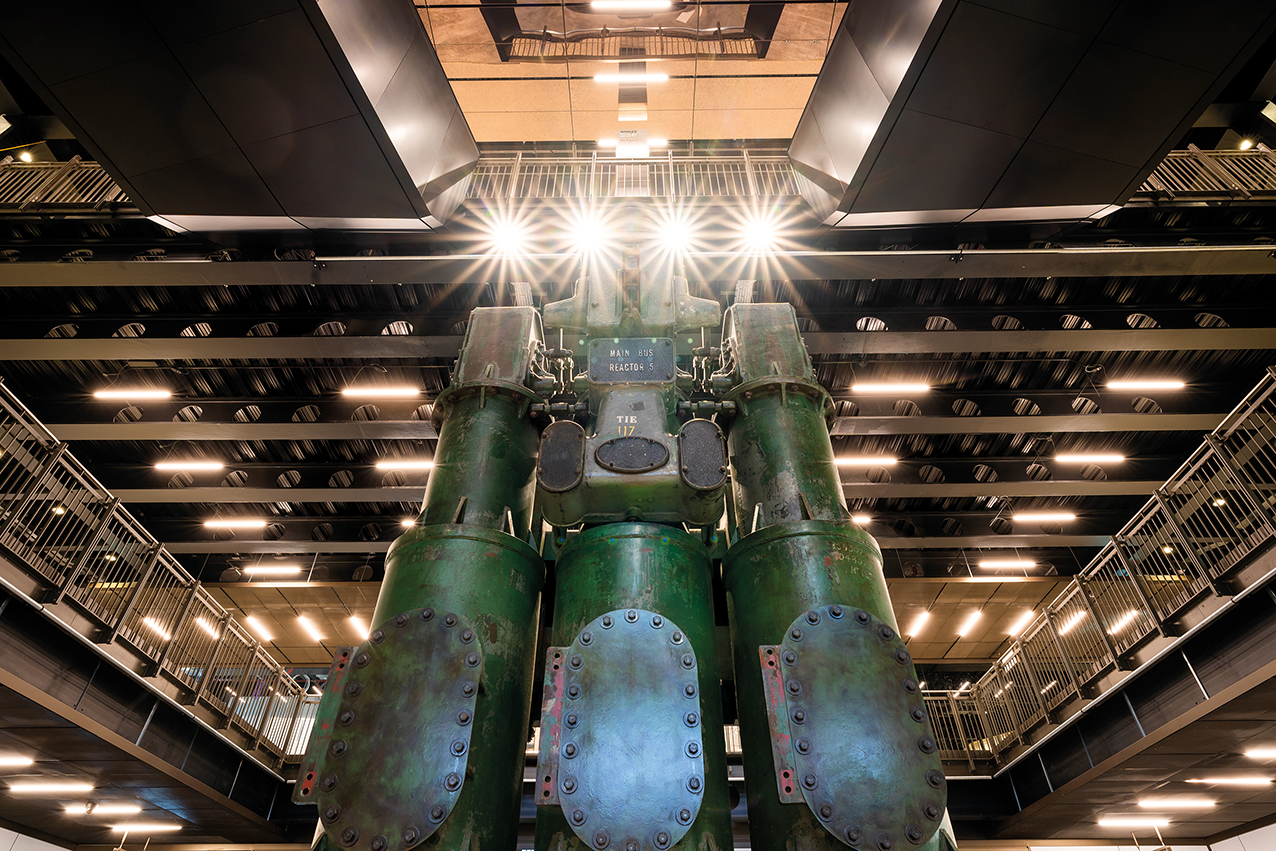

Adjacent to the turbine halls are the original control rooms, with their walls of knobs and dials gleaming like new.

Control Room A is the most impressive, with the banks of breakers – labelled with place names such as Carnaby Street – illuminated by an ornate art deco-glazed ceiling. This is a private events space that will be open to the public on certain occasions. Control Room B, which was built later, is more industrial in design and is now an all-day bar.

The two control rooms have been meticulously restored to be an events space and a cocktail bar

These spaces were originally naturally ventilated. However, because both control rooms are listed, the spaces are now heated and cooled using conditioned air, supplied through existing grilles at high level to the space.

Worth the wait

It may have taken almost four decades and numerous failed development proposals, but Battersea Power Station is finally open to the public, The scheme will benefit the local and wider community, Londoners, and the UK economy, while saving and celebrating the building’s original features – bringing the structure to life once again.

Project team

- Client: Battersea Power Station Development Company

- Architect: WilkinsonEyre

- MEP consultant: ChapmanBDSP

- Structural engineer: Buro Happold

- Lighting designer: Speirs Major

- Cost consultant: Gardiner & Theobald

- Project manager: Turner and Townsend

- Construction manager: MACE