Refurbishment at the UK Green Building Council’s London headquarters. Credit: Morgan Lovell

Life expectancy continues to rise, which is good news – but ageing populations are putting healthcare systems under increasing pressure. In addition, there has been a rise in non-communicable diseases, including those related to lifestyle. In many locations – especially urban ones – air pollution is linked to premature deaths and a range of physical and mental health issues. Health inequalities are significant, even in rich countries. In the UK, for example, there is a difference of nine years in life expectancy and of 18 years in ‘healthy life’ expectancy between the richest and poorest.

These factors are driving authorities towards preventive approaches, and the built environment has a significant role to play – from the indoor spaces where we spend most of our time, to the surrounding outdoor areas and the way we plan our neighbourhoods, towns and cities. Indeed, many health improvements in the past two centuries have been related to measures such as water sanitation, the creation of parks in cities, and the construction of well-ventilated and daylit homes.

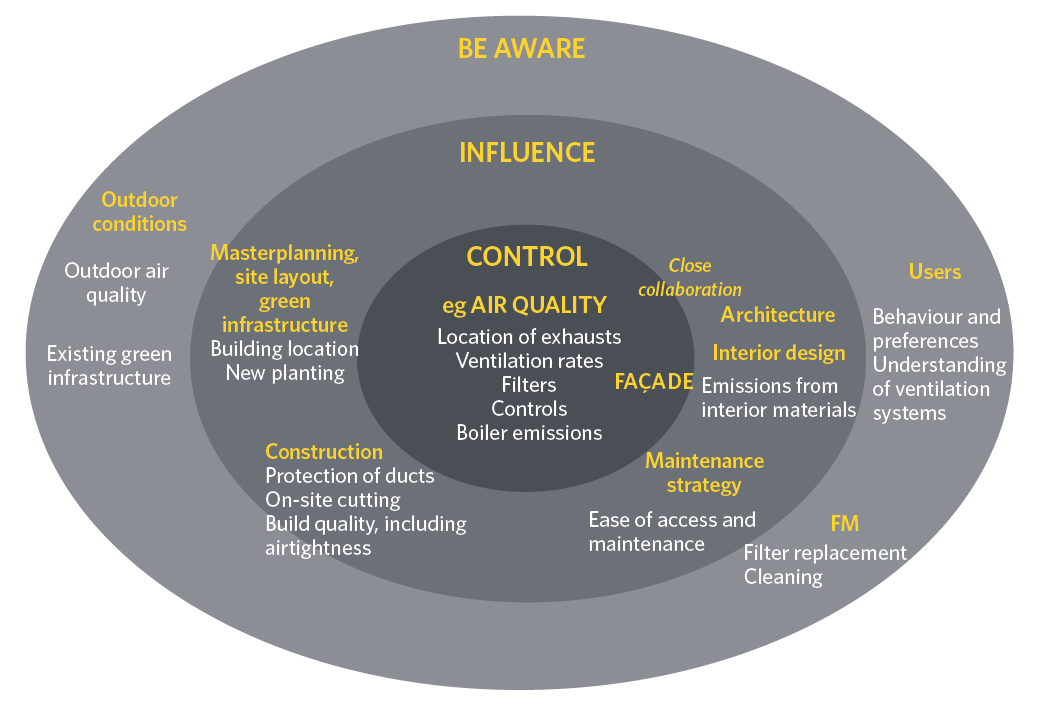

Spheres of influence by building services engineers on health and wellbeing

Advances in knowledge and solutions

There have been significant advances in knowledge and technical solutions in the past decade. These include an increased understanding of the non-visual effects of light on our metabolism, growing evidence of overheating risks, and widespread deployment of LEDs, wireless technologies and consumer devices, allowing building occupants to monitor their environment and activities. All of these have prompted CIBSE to revise Technical Memorandum 40, first published in 2006.

Approach

The scope of ‘health and wellbeing’ is extremely broad, ranging from acute health impacts through comfort and performance, to fulfilment, joy and happiness. The revised TM40 is mostly focused on the middle ground and providing best-practice advice on the design, construction and operation of buildings to support health, comfort and wellbeing. Health and safety issues are highlighted, but mostly with reference to other sources, where they are covered extensively.

Refurbishment at the UK Green Building Council’s London headquarters. Credit: Morgan Lovell

The environmental parameters covered in 2006 – namely, air, humidity, thermal comfort, light, acoustics, electromagnetic fields, and water – are in the new version. There is a broader range of contexts, including new-build, non-domestic environments, homes, refurbishments, and some considerations of external spaces and site layout. It is crucial for designers to collaborate between disciplines and understand the limits of their responsibility. The TM40 steering group and contributors include practitioners, academics, and health experts; guidance focuses on core mechanical, electrical, plumbing and heating (MEPH) issues, but will make clear where awareness of other disciplines is required.

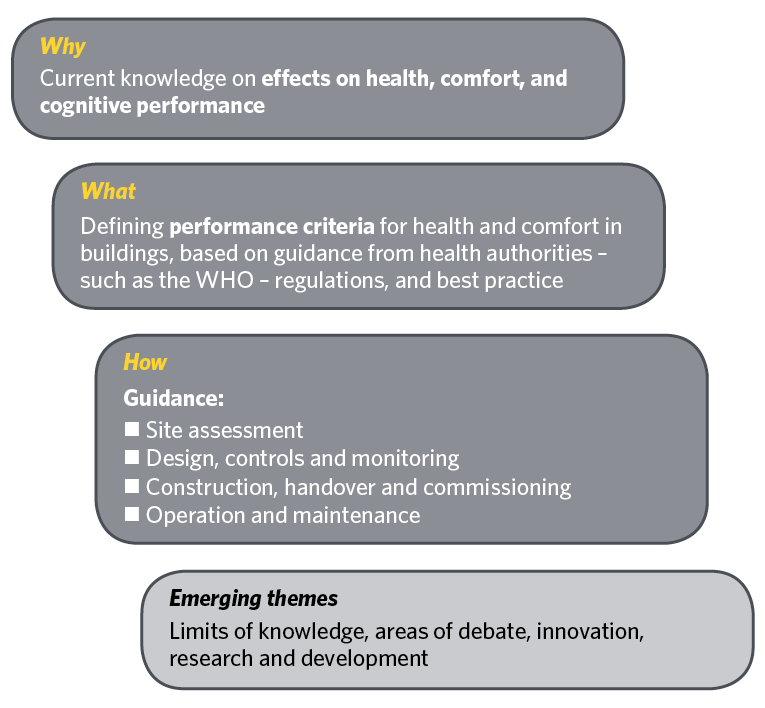

Each environmental parameter is addressed in a dedicated chapter, with the following structure:

Why: This summarises existing knowledge on the potential effects of the parameter on health, comfort and cognitive performance. Important updates from 2006 include the health effects of pollutants from indoor and outdoor sources, the non-visual effects of light, and the potential impact of electromagnetic fields from power lines or wireless technologies.

What: This leads to recommended performance criteria – for example, daylight levels, and pollutant levels in water – which may be used as targets in new designs, or to reference the performance of existing buildings. As a minimum, these should meet regulatory requirements, but also internationally recognised health-based guidelines, particularly those from the World Health Organization (WHO). Regulations in the UK and EU are often more onerous than WHO guidelines; for example, there are currently no comprehensive regulations on indoor air quality, so professionals are strongly advised to refer to WHO.

Structure and approach of each chapter on environmental parameters

This approach to performance criteria is broadly consistent with other emerging guidance, such as BS ISO 17772-1: Energy performance of buildings – indoor environmental quality and the draft revised BB101 Guidance on ventilation, thermal comfort and indoor air quality in schools. It is important to note – in the case of air quality, for example – that the desired outcome is expressed in terms of maximum recommended pollutant levels rather than ventilation rates, as is commonly done. Rates will not necessarily guarantee a suitable outcome, especially if outdoor air is polluted.

How: For each parameter, guidance is given on design, construction and operation. Fundamental rules are to apply source control – to limit the potential hazard in the first instance – and to follow the precautionary principle to avoid unintended consequences, which can manifest themselves in the long term, or on people with individual sensitivities. It is recommended to offer a certain level of user control and choice over environment, to take account of sensitivities and preferences, and increase the likelihood of high comfort and satisfaction levels.

An overview of monitoring approaches is given, to allow building performance assessments, the gathering of lessons learned, and better communication with clients and occupants. The guidance highlights the many overlaps between each issue and with the environmental agenda, both in design, and in operation and maintenance procedures. Occasions where a compromise may be needed, based on project priorities, are also highlighted – for example, between the level of user control and potential energy savings.

It is crucial for designers to collaborate between disciplines and understand the limits of their responsibility

Looking ahead: Finally, each chapter includes a section on emerging themes. This looks at areas under debate, current research and development, and the areas in which professionals should be aware of the current limits of knowledge. These are opportunities for innovation and collaboration with academia. One is the non-visual effects of light, where there is no consensus yet on metrics and solutions. For a live debate, look out for the CIBSE/SLL seminar at Ecobuild.

- More details can be found from Build2Perform, and publication is expected in 2018. To contribute to case studies, contact JGodefroy@cibse.org

- Thanks to all contributors and to steering group members Ann-Marie Aguilar, IWBI; Sani Dimitroulopoulou, Public Health England; Alan Fogarty, Cundall; Keith Miller, GIA; Marcella Ucci, UCL; Sara Kassam and Anastasia Mylona, CIBSE.

- Julie Godefroy is interim head of sustainability at CIBSE