The energy performance gap has dogged the construction industry for years. Buildings have been using much more energy in operation than was intended in their original designs, and evidence of failing buildings – from, among others, Innovate UK – has snowballed in recent years.

Many organisations, including CIBSE, have spent time analysing the reasons for the gap and publishing guidance for clients, consultants and contractors. Initiatives have focused on closing energy gaps – but, clearly, buildings should perform adequately in every way, not just when it comes to energy efficiency.

The Grenfell Tower fire showed the deadly consequences of buildings failing to live up to expectations, and has undermined many people’s confidence in UK construction. We don’t yet know exactly what caused the rapid spread of fire at Grenfell, but tests of similar tower blocks – carried out in the aftermath of the blaze – revealed cladding failing to meet Building Regulations, the potentially lethal absence of firestopping during renovations, and the apparent installation of non-fire-rated doors.

Question marks have also been raised about the ambiguous wording of guidance in Approved Document B of the Building Regulation governing Fire Safety, which may have led to the specification of combustible cladding.

“The identification of risks requires a project culture with time for review and collaboration – that’s Soft Landings”

Shortly after the Grenfell Tower fire, the annual Soft Landings conference took place at the RIBA headquarters in London. Soft Landings is a process designed to optimise the operational performance of buildings and to meet the needs of clients. It focuses on outcomes that can be monitored during the building’s design, construction and operation.

Some conference delegates – including James Warne, co-founder of building services consultant Boom Collective – believe that Soft Landings could help prevent tragedies such as Grenfell from happening again.

‘Disasters like Grenfell are preventable,’ says Warne. ‘The identification of risks requires a project culture with time for review and collaboration. The ethos of this is staring us in the face – it’s Soft Landings.’

The reality-checking process of Soft Landings helped secure a Breeam Outstanding rating for the London Fire Brigade's Dockhead station

At the start of a project, the project team and client set success criteria, which are then checked regularly during design and construction. The Soft Landings Framework stipulates post-occupation evaluation (POE) three years after project completion. (See panel, ‘What is Soft Landings?’) The main focus of this framework is on the energy performance of buildings, and the health, wellbeing and productivity of occupants. However, Dr Michelle Agha-Hossein, sustainable building consultant/researcher at BSRIA, says the principles of Soft Landings can be used to set outcome targets for other areas of construction, such as accessibility and wayfinding.

Agha-Hossein notes that compliance with regulations is not voluntary, so this cannot be set as a success criteria. However, ‘going beyond compliance, where applicable, could be’, she adds.

For too long, says Warne, the construction industry has rewarded projects that have been quickest to build at the lowest cost – meaning quality has been compromised. If the target is compliance, he adds, we must deliver at 100%, but we have an industry culture of falling short.

‘We are missing a policing of quality. This is where Soft Landings come in,’ says Warne, who believes the POE helps focus the mind of the project team. ‘If you tell the design and construction team there will be a test at the end of the project, there is going to be greater care in getting there,’ he says.

Warne believes M&E often gets overlooked in design meetings. However, by focusing on key elements affecting the success of the project in the initial workshops, issues such as overheating or fire safety can be tackled by the whole team – not in silos, but holistically.

What are Soft Landings?

In around 2001 an industry funded task group led by David Adamson of Cambridge University and Mark Way, and including the Usable Buildings Trust and CIBSE, was set up to explore the concept of ‘sea trials’ for buildings. Based on work done by Way for Cambridge and a major pharmaceutical client, this evolved into Soft Landings.

A Soft Landings Framework Guide was written by BSRIA – with the help of the Usable Buildings Trust – in 2009, and updated in 2014. The guide lays out the activities to be carried out at each stage.3 The principles of Soft Landings have been incorporated into BS 8536-1:2015 Briefing for design and construction – Part 1: Code of practice for facilities management (Buildings infrastructure).

Stage 1 Inception and briefing: Designers, constructors and end users spend time with the client to fully understand their needs, design objectives, and roles and responsibilities.

Stage 2 Design development and construction Teams review insights from other projects and engage in reality-checking workshops to ensure design is buildable, manageable and maintainable.

Stage 3 Pre-handover: Teams prepare building for handover, and ensure FM understands systems.

Stage 4 Initial aftercare: Team deals with emerging problems for six to eight months.

Stage 5 Years 1-3 extended aftercare and POE:

Operational performance is optimised through energy monitoring, inspections, fine-tuning, and occupant-satisfaction surveys. Soft Landings champions for the client and contractor ensure objectives are met. In 2016, a form of Soft Landings was made mandatory for all new central government projects and major refurbishments.

It is important that project members collaborate and discuss the interfaces between different design packages. For example, Warne is working on a window curtain package for a workplace project that has an impact on the design of controls, cladding, M&E and flooring. He has drawn a sketch with labels that clearly explains the interrelationships between packages (see version of this article at www.cibsejournal.com).

Warne says that specifications written purely in engineering terms are in danger of being ignored, and are never readily available onsite. ‘A sketch with clearly written clauses help the rest of the project team understand the engineering,’ he says.

Lessons learned

A key element of Soft Landings is the passing on of knowledge to subsequent projects. ‘The UK industry has a good design process for innovation, but we don’t have a good way of passing on lessons learned from project to project,’ says Warne.

‘The learning loop is important,’ adds Alasdair Donn, a principal consultant at contractor Willmott Dixon, who says his firm is committed to the philosophy of Soft Landings, and employs an in-house team to study the operational performance of some projects. ‘We learn a lot from how things perform. We’ve selected some projects and followed them after handover.’

Warne views Soft Landings as closely tied to the ‘new professionalism’ described in a debate initiated by cross-profession group the Edge in 2013. It proposed that professionals needed to have a stronger role in protecting the public through leadership, impartiality, and sharing knowledge and expertise. The debate outcome proposed a better procurement process and more knowledge about performance in use – both core principles of Soft Landings.

“The Framework works on small and big schemes, and only the scale and frequency of some activities may change depending on the size and complexity of the project”

Soft Landings can also be cost-effective, says Agha-Hossein. ‘There is perception among clients that Soft Landings is expensive, but it should not cost anything up until POE,’ she adds. The POE element of Soft Landings is an addition to standard forms of procurement, so requires additional funding. Depending on the size and complexity of a project, £30,000 to £60,000 is a reasonable range to fund a three-year POE, according to Agha-Hossein. ‘These costs are modest compared to the cost of unhappy occupants and the potential cost of high utility bills from a non-performing building,’ she says.

Mike Chater, senior architect at Hampshire County Council, agrees that Soft Landings can be perceived as expensive. ‘It was clear against the context of cuts in the public sector that it would only gain traction if it was low or zero cost,’ he says. ‘I did a mapping exercise to overlay the Soft Landings Framework on our processes. We found we only had to make a small tweak to our practice to align with it.’

Chater says it is difficult to justify employing Soft Landings champions on small projects; in Hampshire this role is assumed by the architect during design and construction, who is joined by a property-management surveyor to engage with schools after handover, to check on operational issues during the defects liability period. The council is now applying Soft Landings on a £200m-plus school building/refurbishment programme (see panel, ‘Soft landings in practice’). On large secondary school projects, POE is worth the investment, according to Chater. Where there is no POE, Hampshire includes Soft Landings activities in preliminaries for bidders, and expects them to be zero cost.

Soft Landings in practice at Hampshire County Council

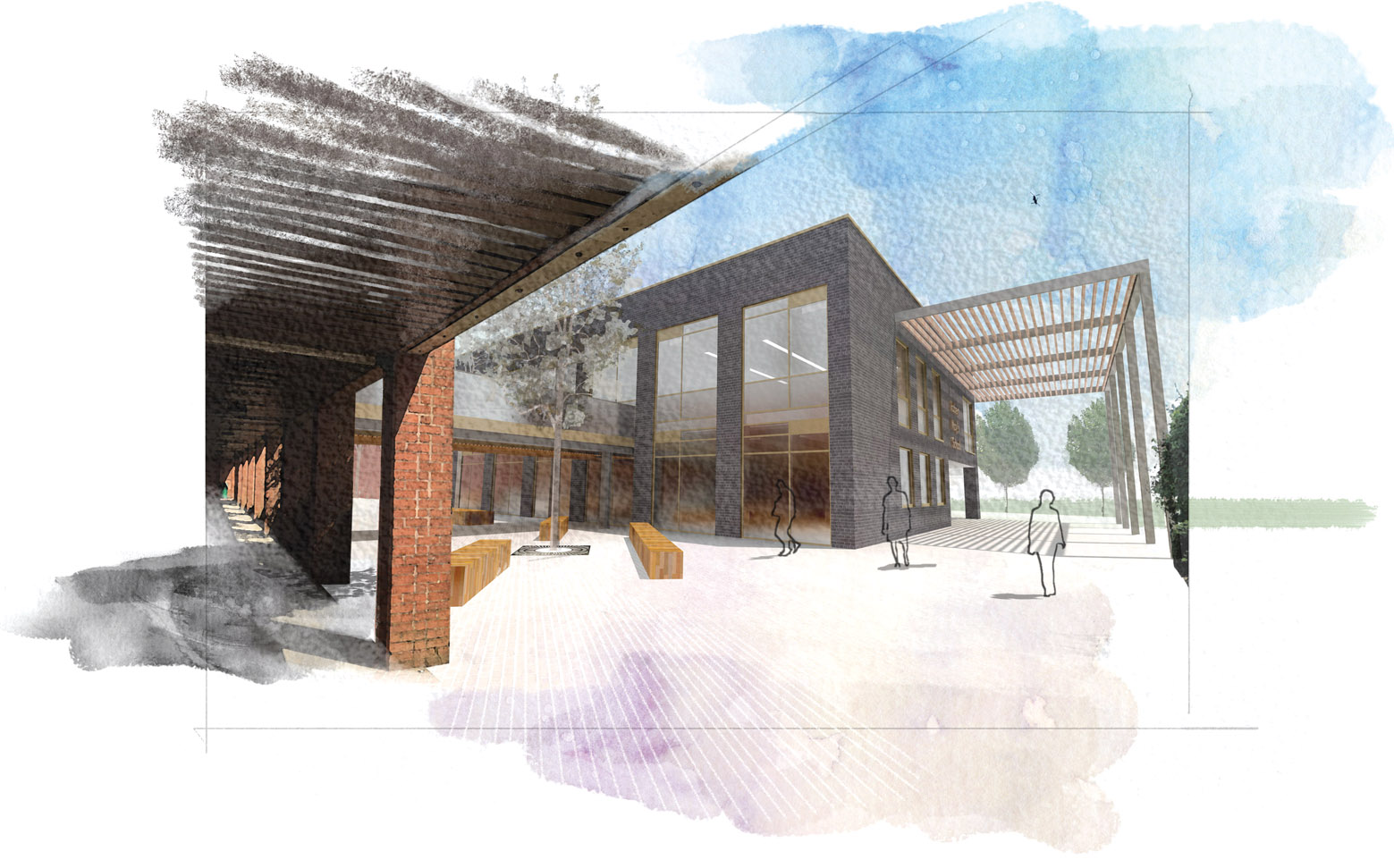

Design for expansion of Robert May’s Secondary School, where Soft Landings will be applied

Hampshire County Council is applying Soft Landings across the majority of its school expansion capital programme, worth more than £200m in total. Mike Chater is a senior architect in the practice and explains how it works

One of the most important actions is to set up a Soft Landings workshop, which normally takes place at the end of Riba Work Stage/3/D. This brings together interested parties, including the client, headteacher, business manager, services engineers, contractor, caretaker and property-management representative, who has responsibility for ongoing maintenance. This workshop is key, as it’s often the only opportunity to get everyone together.

Participants are encouraged to voice any potential issues that could compromise the success of the project. Discussions are split into ‘activities’, which cover ‘architecture and interiors’, landscaping, building services and controls. People associate Soft Landings with building services, but it can be used to flag up any design and operational issues. For instance, the school business manager in a secondary school asked that the landscaping in front of her office didn’t obscure her view of the courtyard in the summer; maintaining clear views of this area was an important part of the school’s strategy for safeguarding children.

Notes from the workshop are collated into a spreadsheet, which lists the risks that have been identified, alongside lessons learned from previous projects. It also outlines a series of actions to mitigate the risks, which are apportioned to the design, construction/commissioning and operation stages of the project. We encourage regular reviews of this document to check if the actions to mitigate risk have been completed. This is led by the architect (client’s Soft Landings champion) and the site agent (contractor’s champion). We call it the ‘defects risk schedule’, as contractors are familiar with the term zero defects, so take note. Value-engineering decisions are also reviewed in the Soft Landings process.

If risks have been highlighted but not actioned, you can go back to the document at defects stage to get them rectified. The schedule is our history of ‘old chestnuts’, which get fed into our ‘design and technical and review’ process, so there is an awareness of them for future projects.

Our handover phase is expanded from the original BSRIA Soft Landings Framework. We have created another onsite workshop, which happens two to three months before handover or the first major sectional completion. It is held on site with the contractor and school, and is about working backwards from the completion date to ensure all parties understand their responsibilities for ordering, supply and install. At handover, we also make sure we have a firm commitment to seasonal commissioning dates.

Finally, we plan a series of meetings during the aftercare period, using the defects risk register to inform the fine-tuning of the building. We ensure more collaboration with our property management surveyors, who will take over the FM as part of our service level agreement with the schools – so it is in everyone’s interest to ensure familiarisation with both the building and services during a 12-month defects period.

To get full value from Soft Landings, Warne believes clients should carry out POE – but if there is not the budget, they could at least work with someone to identify risks to the project.

Agha-Hossein says Soft Landings can be adopted on any building project; the Framework works on small and big schemes, and only the scale and frequency of some activities may change depending on the size and complexity of the project. BSRIA is currently looking at creating a Soft Landings framework for residential buildings.

Donn claims adoption of Soft Landings among clients is increasing, with some seeing the light after previously suffering problems in construction and operation. ‘Clients have seen how Soft Landings have given them less risk and more certainty in operation,’ he says.

For the process to really catch on, however, there needs to be more flexibility in contracts, adds Donn, who says a number of clients are working Soft Landings into contractual frameworks, and focusing on outcomes. ‘They are adding employer’s requirements of the design team and contractor to carry out Soft Landing activities.’

Chater says Soft Landings offer a stepping-stone to better collaboration with other professions and he urges his fellow architects to become more engaged with the Soft Landings process. ‘If we can’t design buildings that function well, we’ve failed at our job,,’ he says.

Warne agrees, and says Soft Landings enables greater collaboration, which fosters mutual respect and better integration of design solutions. He believes Soft Landings should become an integral part of everyone’s work process. ‘Our buildings are not performing,’ he says. ‘They’re failing left, right and centre. Soft landings should not be a choice.’