SLL president Iain Carlile with past president Richard Caple

Lighting design should always start with the person for whom you are designing, and their needs and requirements, says Iain Carlile, associate at dpa lighting consultants.

The new Society of Light and Lighting (SLL) president wants to spread the message about good lighting to the general public, as well as the wider construction industry. ‘Good lighting has to be visually comfortable, and designed for the person and the task they’re doing,’ he says. That task can vary, so the light also needs to be variable, and avoid glare and excessive contrast.

Iain Carlile

When a space is badly lit, you know it, adds Carlile. ‘We’ve all been in a restaurant where the lighting has been badly focused, shining directly into your eyes causing glare when you’re supposed to be looking dreamily at the person sitting opposite you. A well-designed lighting scheme is one you don’t necessarily notice, because you enjoy the space for its function and appreciate the beauty of the objects being lit without being distracted by the lighting equipment.’

It should also change during the day. ‘For example, a restaurant should be light and airy in the morning during breakfast, and – in the evening – intimate and low-key, and all about the person you’re having dinner with, isolating you from others around you,’ says Carlile.

This, he adds, can be achieved with controls. The change between daytime and evening scenes can be set over a 10-minute fade, so you don’t notice it changing. It can also be linked to time clocks, based on sunset and sunrise. ‘In the summer, 9pm is completely different from 9pm in the middle of winter, so your lighting needs to adjust to the time of day and the time of year,’ says Carlile, who believes these nuances can mean the difference between a good and bad lighting design.

Technical roots

Cynics would say lighting consultants ‘point and squirt’, but Carlile points out that you need to be able to validate and prove your designs, especially where lighting levels are critical. ‘At concept, what we do is typically more visual – selling the idea about how the spaces might look to a client – but it has to be grounded in sound technical knowledge. There’s no point presenting a concept that won’t work technically.’

A well-designed lighting scheme is one you don’t necessarily notice, because you appreciate the beauty of the objects being lit

A lot of technical knowledge is needed to specify the right type of luminaires, to ensure the light source is correct, and to understand the technical properties of the light specified, he adds. ‘What is the spectral distribution of it? How is it controlled? How does it interface with the dimming system? You need to understand and interpret requirements – that vary from country to country – to ensure they are met, while creating a stimulating and interesting environment.’

Such understanding is especially important at the schematics stage, when the concept is interpreted into detailed drawings and specifications, and coordinated with other teams. ‘We don’t work in a vacuum: successful projects have cooperation between teams. A firm background in engineering has helped me with that interface,’ he says.

The future of tech

The continual refinement of light-emitting diode (LED) lighting fascinates Carlile, who believes its development is akin to an arms race between manufacturers trying to get more lumens per watt – sometimes at the expense of light quality. ‘As LED has become more commonplace, the quality of the light has improved and the spectral distribution has got better, so the colour appearance of the objects being lit has also improved – which has enhanced the visual effect,’ he says.

But tendencies still exist to use lighting with a cooler, more aggressive appearance in the built environment. ‘Just because it has the highest efficacy doesn’t mean it’s the correct thing to do. We must not forget who we are lighting for – the people who use the spaces.’

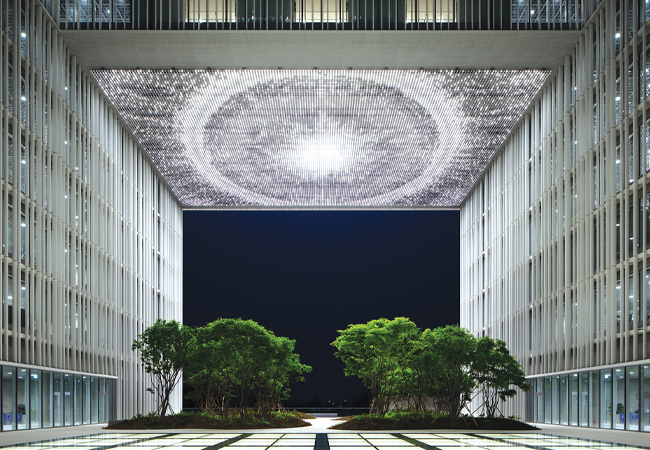

dpa lighting consultants’ lighting design at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel, Geneva

Although a cooler colour temperature lighting has benefits – studies show a cooler white-light source can make people more alert, allowing you, in theory, to light to lower levels – human visual perception at such levels responds better to warmer light temperatures. ‘That’s probably because we’ve spent hundreds of thousands of years evolving with nothing but fires at the edge of our caves, and candlelight,’ says Carlile.

More lumens per watt and more luminaire efficacy are good, but they shouldn’t be looked at in isolation, because human visual comfort, glare, colour temperature, and how a space is used have to be taken into consideration. ‘There’s also the deception that, if it’s LED, it must be good,’ says Carlile. ‘There’s a lot of LED out there with varying quality.’

For years, he adds, the lighting industry for domestic use got it wrong, marketing lamps using wattage. Thankfully, with the introduction of LED lamps – not bulbs – lumen output, colour temperature and colour rendering are now widely used terms. And, with the advent of wellbeing standards, there is a growing understanding of how light colour temperature and intensity affect circadian rhythms. ‘But there are a lot of unknowns. Lighting affects mood, but humans are complex and everyone is affected differently.’

Seeing the light

As a child, self-professed geek Carlile was interested in science fiction, Doctor Who, the A-Team, Lego, and Airfix kits. He studied science and maths at A level, and spent a year at British Nuclear Fuels’ Magnox Generation Group, working as a computer programmer – a job he soon realised wasn’t his passion.At the University of Exeter, Carlile studied general engineering before specialising in electronic engineering. During his summer holidays, he worked at Swindon-based building services consultancy TDP, where he was exposed to all aspects of building services engineering. ‘But my interest always lay in electrical and electronics – and lighting design really grabbed me.’

At the time, his interest in lighting was numbers-driven – what did 500 lux look like? ‘I was trying to understand how the numbers related to how someone envisaged the space. Later, I worked out that numbers only get you so far. Lighting is the one part of the built environment I believed could influence people, because a large part of their appreciation of a space comes from how they visually perceive it.’

Carlile joined Whitbybird – now Ramboll – as a graduate electrical engineer and started the light and lighting Master’s course at UCL’s Bartlett School of Architecture. ‘I had more appreciation for lighting architecture and human perception, rather than just the numbers – the artistic side was marrying up with the engineering side.’

In 2004, Carlile joined dpa lighting consultants, working his way up from a designer to associate.

There are other issues, too. A lot of energy marking only considers ‘as installed’ electrical lighting load, but – with dimming and scene-setting – some lights may be at 100% of their output at certain times of the day, and 5% at other times, which helps extend the life of the luminaire and lower in-use energy cost. ‘Where local requirements only work on installed load, or give you allowance for controls nowhere near what you might be using, it is a challenge. Good lighting should be a benefit to everyone, so educating people is important,’ says Carlile.

During his SLL presidency, Carlile aims to engage with the membership, making sure that what the society is doing – and plans to do in future – is relevant.

‘I want to spread the word that all people involved in lighting can be members of the SLL. The society gives people the tools to help them progress in their careers and achieve professional recognition through membership grades, as well as offering guidance, events and networking opportunities.’

He also wants to build on previous SLL presidents’ work in promoting lighting as a career to young people. Having lit everything from a single piece of artwork to a city masterplan, Carlile enjoys the varied nature of his work and wants to show how exciting a career in lighting could be.‘We see wonderful spaces expressed with light, and it sparks inspiration.’