The scheme’s CSH Level 5 homes are built from Kingspan’s Ultima timber frame system

Choice Housing Ireland (CHI) wanted its 39 homes in Killynure Green, Carryduff, south-east Belfast, to show developers it was possible to build low energy housing without a radical approach to construction or an over-reliance on renewable technologies. So it built Northern Ireland’s first Code for Sustainable Homes Level 5 (CSH Level 5) scheme.

The £7m development was completed in October 2015. Two years on, this innovative scheme is living up to expectations, with residents saving up to 42% on the cost of energy, compared with a similar-sized dwelling, and with CO2 emissions 60% less than the Building Regulations minimum.

The scheme’s pragmatic approach to low energy housing impressed at this year’s CIBSE Building Performance Awards, where it won Project of the Year – Residential. The judges said: ‘Killynure Green was a really commendable approach to a social housing scheme’, and praised the fact that it incorporated ‘lots of references to lessons learned from previous projects that they had reviewed and improved on’.

To design the CSH Level 5 scheme, CHI worked with PDP Architects and engineers Caldwell Consulting. ‘We developed the first Code Levels 3 and 4 schemes – and the first certified Passivhaus social housing – in Ireland. This scheme demonstrates our appetite to try to deliver the best service and homes for tenants that we can,’ says Brian Rankin, energy manager at CHI.

As well as meeting CSH Level 5 criteria, the designers had to ensure the scheme met the requirements of Lifetime Homes and Secured by Design, and the space parameters set by the Department for Communities (DfC).

The design

Killynure Green is built on a sloping site. The architect’s design exploits this gradient by arranging the two-, three- and four-bedroom homes in terraces along its contours. Homes are orientated to face north-south.

Their northern elevation incorporates a big feature window, allowing large amounts of daylight to enter the homes without the need to control solar gains. By contrast, the southern elevation incorporates a double-height, single-glazed wintergarden. This is designed to collect solar gains in winter, with air warmed by the sun drawn into the homes through opening doors and windows. The wintergarden is intended to reduce the home’s heating load. In summer, shading elements and opening vents allow occupants to purge unwanted heat from the space.

The CSH Level 5 homes are built using a proprietary Ultima Timber Frame System – a prefabricated structural system, selected by contractor GEDA Construction to achieve high levels of thermal insulation and airtightness. This off-site solution ensured fabric U-values could be kept between 0.11-0.16 W.m-2.K-1.

The southern elevation incorporates a double-height, single-glazed wintergarden to collect solar gains in winter, with air warmed by the sun drawn into the homes through opening doors and windows

In addition, enhanced accredited construction details were used to achieve Y values (the proxy for the heat loss through the non-repeating thermal bridging areas of a building) of 0.04 W.m-2.K-1 by minimising thermal bridges. Where details differed from standard enhanced details, thermal modelling was carried out to test junctions. All windows are triple-glazed.

Airtightness tests were carried out once the building envelope had been completed, but before the internal linings were finished. This approach proved effective, with the homes having a permeability of between 2-3m3/m2.h at 50Pa on completion.

Although the homes are highly insulated, they are not designed to Passivhaus standard. One reason for this was the experience CHI had when developing the first certified Passivhaus social housing scheme in Ireland. Rankin says it found that monitored energy consumption for the scheme was ‘higher than expected because of unrealistic expectations around air permeability due to occupants having the freedom to open windows’. In addition, he says, ‘the design team felt that attempting to achieve Passivhaus standard on this project would involve additional cost’.

The homes do, however, include a mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) system to remove stale air and provide fresh, filtered and warmed air. The system is fitted with a summer bypass to supply cooling in warmer weather.

The original design proposed solar thermal panels to heat a thermal store that, in turn, would supply domestic hot water and heat for an underfloor heating system. The system would also have included an air-to-water heat pump for top-up heat. This proposal was abandoned, however, to be replaced by a condensing combination, natural gas boiler-based solution, which was expected to have lower capital and maintenance costs.

‘This switch is one of the main reasons the scheme has performed so well,’ says Rankin. ‘There were no objections from the design teams; they were happy to consider an alternative approach and review its benefits in light of various changes to market conditions and financial incentives for renewables.’ Using gas-fired combi boilers also supported the idea that the scheme could be easily replicated by others.

The impact of the change was a capital cost saving of more than £50k, reduced CO2 emissions and energy costs, and a simpler system to design, install and maintain. Without the solar thermal panel, the size of the roof-mounted solar PV array could be increased to 4kWp, significantly raising the amount of renewable electricity generated. This, in turn, increased the value of the Renewable Obligation Certificate (ROC) payments that could be claimed by CHI over the scheme’s 20-year life, along with payment for exported electricity. Payback for the PVs is expected to be about six years.

Happy handover

Its experience from earlier projects meant that CHI understood the importance of commissioning systems appropriately, and the critical nature of the handover process – from contractor to housing association and housing association to tenants – so everybody understood how to benefit from the homes.

A pre-handover visit took place with the design team, contractor and housing association, to highlight the technologies within each home and to explain how these should be used. Potential tenants were also invited to information sessions, to give them more detail about the scheme and help them decide whether to accept the offer of a home.

Groups of those who decided to move in were then invited to visit the development for a 30-minute presentation in one of the properties, before the keys were handed over.

After the presentation, each tenant was taken to their home so the heating controls, for example, could be set up appropriately for each household. A home user guide was also produced, containing information on the development, plus explanations of the different features, including the wintergarden, MVHR and PV systems. The main contractor and subcontractors were available to help support the handover process.

CHI’s involvement in the detailed monitoring of its passive house development highlighted the cost implications and technical challenges of this approach. For Killynure Green, it opted simply to collect twice-yearly meter readings for the solar PV systems, and annual electricity and natural gas consumption readings. During these visits, tenants are able to raise questions or ask for further support.

Consumption and cost

All the Killynure Green homes achieved an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) A rating. This indicates that average energy consumption is expected to be 35kWh/m2, with average CO2 emissions of 6kg/m2. The average annual energy running cost for each home is predicted to be £409. The EPCs exclude unregulated energy, such as that used for cooking and by appliances and electronic equipment.

After one year of occupation, in October 2016, meter readings were taken for every home. They showed the overall energy used within the properties was less than the national average for Northern Ireland. For the two- and three-bedroom properties, the average annual total energy costs were £564, compared with the Northern Ireland average for similar-sized properties of around £877 (based on National Energy Efficiency Data in June 2015). This represents a reduction of around 36% for occupants.

All of Killynure Green’s 39 homes have an EPC A rating

For the four-bedroom properties, the average annual energy costs were £682, compared with an average of £1,169 for a similar-sized property – a difference of 42%. Of these total energy costs, each home is paying about £250 per year for heat and hot water.

The solar PV system was expected to generate around 3,108kWh of electricity each year for each home. However, the first year’s analysis showed the PV systems generated an average of 3,318kWh at each property – 7% more than expected – with 28% being used within each home.

The electricity generated by the PV is available free for residents to use, with unused electricity exported to the grid. ‘Tenants can use as much of the generated electricity as they want,’ says Rankin. At the moment, however, they are only using, on average, 28%. If they were to use 60%, tenants would benefit from an additional saving of £160 on their electricity bills. ‘If a number of residents are out working during the day, they may not want to leave equipment running and may not be available to use the solar-generated electricity,’ Rankin explains.

There is a difference between the EPCs’ predicted energy costs and actual energy costs of around £200-250 in each home. Two factors account for this: the proportion of renewable electricity from the solar PV used in each home, and unregulated energy use.

CHI is able to claim Renewable Obligation Certificates (ROC) payments for the PVs, along with payments for exported electricity. In the first 12 months of occupation, Choice received approximately £580 per property in relation to the solar PV systems. According to Rankin, this highlights the benefit of this approach to building new homes. ‘In a private development, if the ROCs and payments for exporting solar PV were made to the homeowners, the average overall annual cost of energy for these homes would be – £90 for each property, so tenants would actually make £90 a year in relation to energy,’ he says.

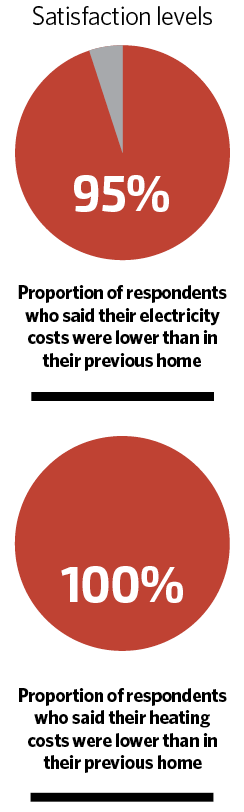

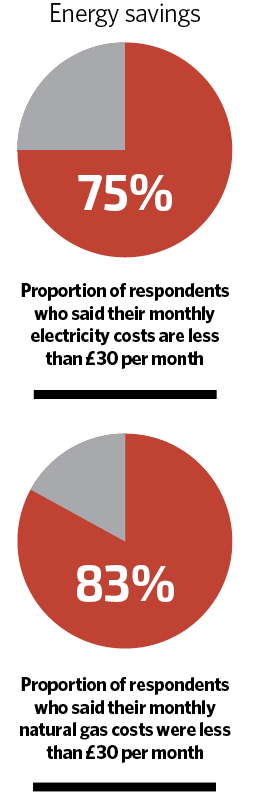

Even without ROC payments, responses to surveys indicate that tenants’ satisfaction levels are high, with 95% of respondents stating that their electricity costs are lower than in their previous home, and 100% saying their heating costs are lower. In addition, 75% of respondents reported that their monthly electricity costs are less than £30 per month, while 83% said their monthly natural gas costs were also less than £30 per month.

Design for the second phase of homes is now under way, and these properties will also be on social housing tenures. As the Code for Sustainable Homes no longer exists, CHI’s intention is to pilot this second phase to a new, optional, energy efficiency standard outlined by the DfC. These new homes are expected to be some of the first developed in this way in Northern Ireland.