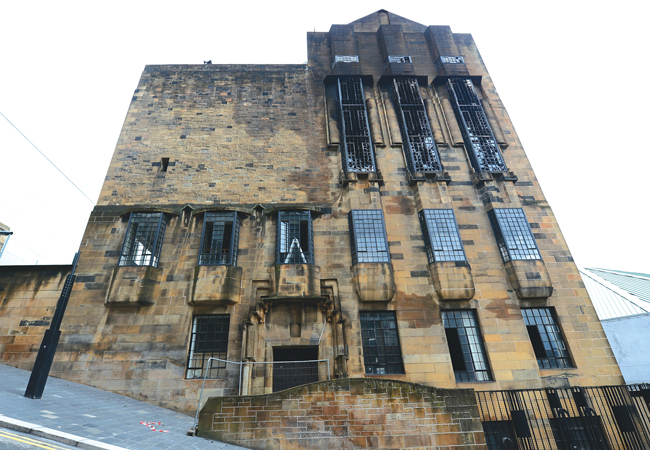

Mackintosh Building. Credit: Getty Images Jeff J Mitchell

On 23 May 2014, fire spread rapidly through The Glasgow School of Art’s (GSA’s) hallowed Mackintosh Building, completed by architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh in 1909.

The fire began in the basement of this Scottish art nouveau gem, and quickly moved upwards – through three levels of studios – and outwards, to the first-floor library. Although the blaze was brought under control relatively quickly, significant damage was done to the historic studios and stairways of the grade A-listed building, and the renowned Mackintosh library was destroyed.

Scottish Fire and Rescue Service’s report said the fire started close to a hot projector. The report also found that the design of the building contributed to the spread of fire, as there were a ‘number of timber-lined walls and voids, and original ventilation ducts running both vertically and horizontally throughout the building’.

Three years after the blaze, those same timber-lined ventilation ducts form a key element of engineering consultant Harley Haddow’s building services strategy for the property’s refurbishment. The design team for the restoration is being led by Page\Park Architects, who have worked closely with experts at the GSA researching both original documentation and what the fire has revealed about the design of the building.

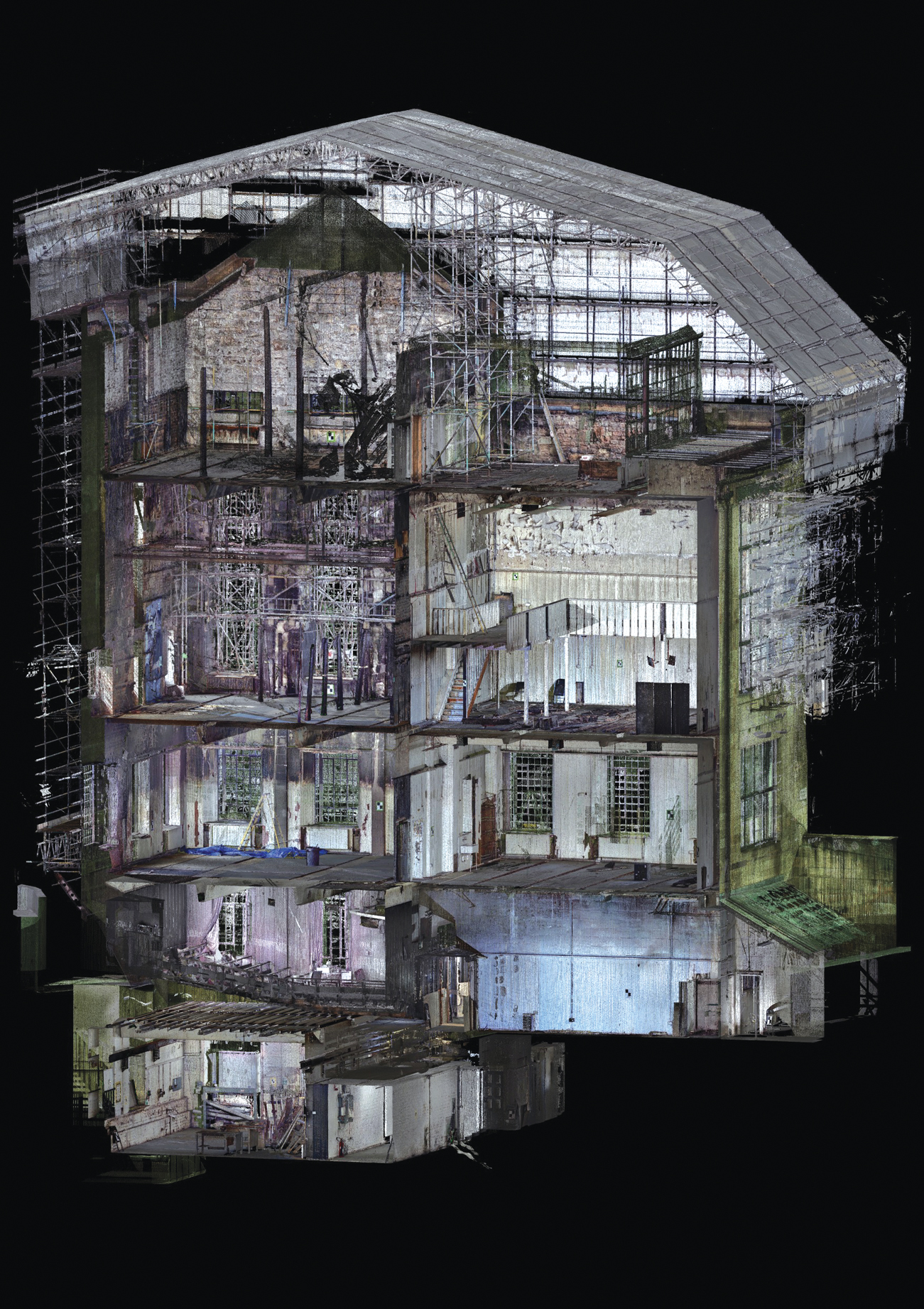

Scan of Professors' studios looking north to south at Mackintosh Building. Credit: School of Simulation and Visualisation (SSV), Glasgow School of Art

‘A key aspect of the project is The Glasgow School of Art’s decision to restore the building to Mackintosh’s original design while providing an energy efficient, technologically advanced and flexible teaching environment for today’s students,’ says Mark Napier, a director at Harley Haddow. Napier has drawn on more than a decade of involvement with the Mackintosh Building to develop the design.

Harley Haddow’s first experience of ‘The Mack’ was in 2006, when it worked with Page\Park Architects to remodel part of the building to create a furniture gallery and shop, relocate the reception, install an archive store in the basement, and fit a new piped radiator heating system. Subsequent works in 2008 involved the removal of some of the mezzanine floors that had been added to the studios over the years. Fan convectors – installed in the 1980s – were also stripped out to take the studios back to their original form.

Over the next few years, Harley Haddow’s ongoing involvement with The Glasgow School of Art resulted in the consultant doing ‘small bits and pieces’. Its next major project was the installation of a fire-suppression system. The GSA needed a solution that was appropriate for a Category A-listed building, so it opted for a high-pressure-mist fire-suppression system to help protect the building. Work on this was not completed at the time of the fire.

Using Mackintosh’s original drawings

Afterwards, Harley Haddow returned to the building as advisers to the fire scientists who had been commissioned by the School’s insurers to investigate the incident. ‘We spent a lot of time helping them to understand how the original ducted warm-air heating solution worked, and how these ducts might have contributed to the spread of fire through the building,’ says Napier.

Mackintosh’s original drawings showed the building’s central spine wall to be perforated by scores of these brick-lined flues rising vertically upwards from the basement. They also depicted a further series of ducts rising from the rooms and studios, and terminating at roof level. ‘The drawings were pretty accurate, although not everything was on the drawings, so Harley Haddow had to survey the building,’ Napier explains. ‘The survey even included dropping plumb lines down some of the ducts to confirm their routes.’

The ductwork system was intended by Mackintosh to heat and ventilate the school with filtered, tempered air, which would avoid the need to clutter the interior with large, unseemly radiators. Fundamental to the system is a brick-built air shaft, which runs below the floor the length of the basement. It is, in effect, a giant air plenum. From the top of this shaft, ‘hundreds’ of wood and brick-lined flues duct air vertically up through the building.

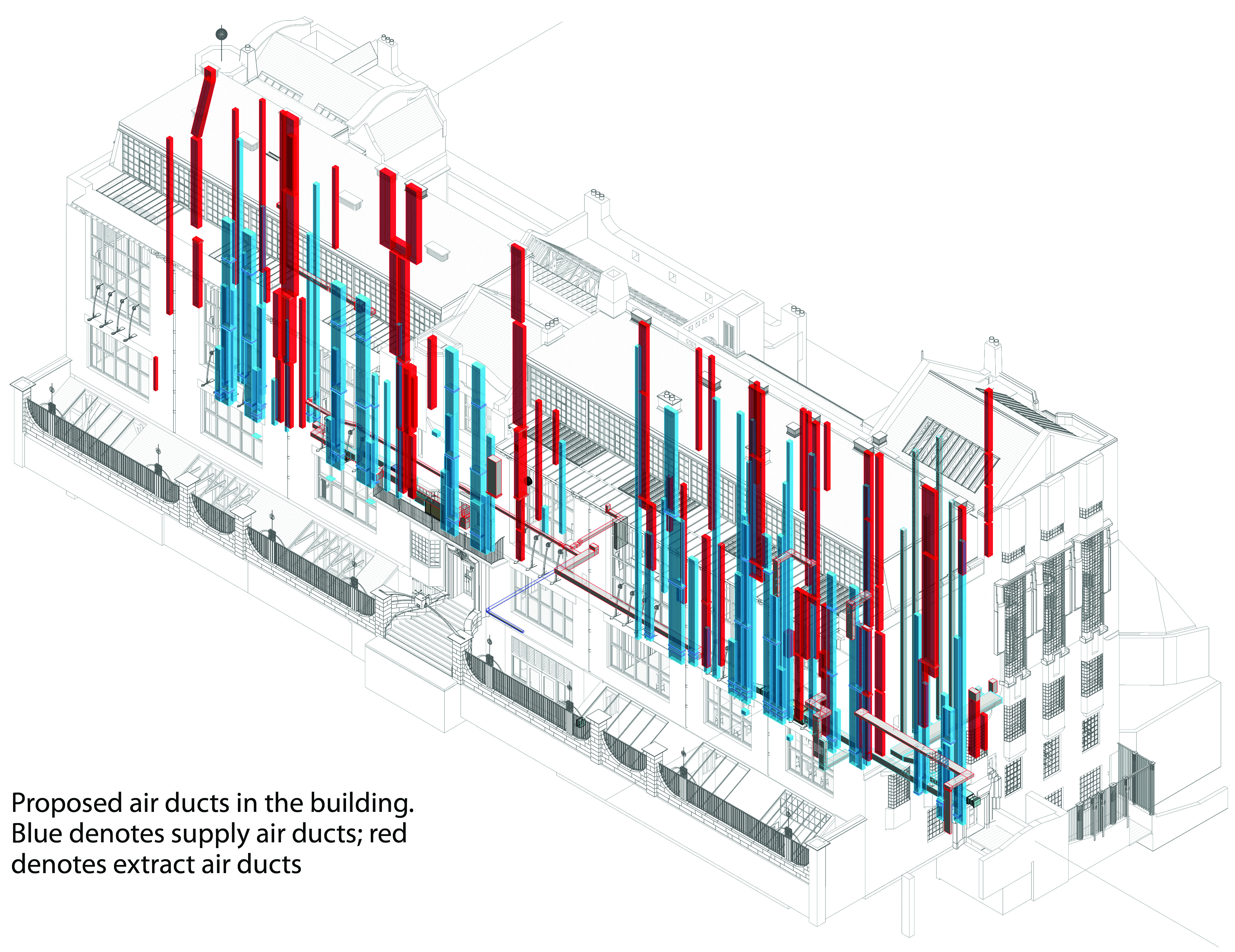

‘Every room has at least one air duct terminating inside of it,’ Napier explains. Harley Haddow modelled each and every duct in a 3D Revit model.

The tempered fresh air is delivered to the rooms by these ducts. The system was designed to supply 36m3.s-1 of outside air, drawn from light wells either side of the main entrance and pushed into the basement air shaft by two large, belt-driven centrifugal fans (which are still in place). When the School of Art was constructed, Glasgow would have been a sooty, industrial city so the system used horsehair to filter the outside air. If needed, the filters could be sprayed with water to create a rudimentary humidification and cooling solution. The cleaned air could then be warmed as it passed over a series of steam coils fed with heat from a coal-fired steam boiler. Records show the tempered fresh-air system was installed in two phases by the Glasgow firm of James Cormack & Sons for the sums of £1,454 and £716.

Ahead of its time

In addition to the ducted air supply from the basement, the rooms feature wooden ducts that rise up through the building to vent air out. These exhaust-air ducts terminate either at roof level or at a louvred section set into the rear wall of the building above the ground-floor central corridor. In many of the rooms, the exhaust ducts are fitted with two grilles, one close to the ceiling and one near to the floor. ‘The idea is that, in winter, a damper on the high-level grille is closed to force the warm air down into the room; in summer the top grille is opened to let warm air escape from the room,’ says Napier.

This innovative environmental engineering system was, perhaps, ahead of its time. ‘There were a lot of letters between the contractor and The Glasgow School of Art about there being too much heat in some rooms and too little in others, especially the library,’ adds Napier. There is even a note of the scheme’s coal consumption, which averaged 13.5 tons per week while the system was being snagged from 31 January to 5 March 1910. The same note goes on to say: ‘We [the GSA] are inferred by the contractor that this is a very moderate consumpt [sic] of coal.’

Mackintosh Building library before the fire. Credit: ©McAteer

Regardless of its coal consumption, the system could not be made to work effectively, so was abandoned in 1920 and steam-fed radiators installed in its place. In 1986, these were also supplanted, by a low pressure hot water (LPHW) system of cast-iron radiators and fan convector heaters, and it was this set-up that Harley Haddow’s LPHW heating system was designed to replace in 2008. Now, under the restoration works, this scheme is being largely superseded too.

‘The 2008 system was installed in a live building, so the GSA is taking full advantage of the restoration project to conceal the pipe routes and remove the radiant panels from the large studios. As the thermal performance of the building’s fabric has been improved, some of the radiators are now smaller,’ says Napier.

Return of the Mack

The initial focus of the restoration was on repairing the fire-damaged building envelope to make the building watertight. Work to restore and upgrade the building interiors is now taking place. For the GSA, the restoration is an opportunity to take the building back to the Mackintosh original conception by removing later additions and modifications to the spaces. At the same time, the restored building needs to function as a facility for today’s students.

‘The Glasgow School of Art’s philosophy is to bring the building back to its original design, but to make it function as a modern art school,’ says Napier, ‘which is an interesting brief for the design team because the GSA needs power, data and LED lighting, while – at the same time – respecting Mackintosh’s original.’

The School of Art was one of the earliest buildings to feature an electric lighting system. Now, more than 100 years later, the Mackintosh Building is being fitted with a state-of-the-art, LED-based lighting scheme, designed by consultancy KSLD. It is intended to offer flexibility of use within the studio spaces, which can range from fine art to computer labs, and can also be configured as exhibition spaces.

Reusing timber ducts

The GSA’s quest to be true to Mackintosh’s original conception involves resurrecting the abandoned timber-ducted ventilation system. This time round, though, it will only be used to supply heated fresh air to studios, the library, the Mackintosh Room and lecture theatre – and, rather than relying on two giant centrifugal fans, two air handling units (AHUs) will each deliver 3m3.s-1 of air. The original fans will remain in place, so the AHUs will push air over them and into the basement air duct.

‘We’ll only be pushing 6m3.s-1 of fresh air into the basement air duct to provide ventilation air for the occupants, not 36m3.s-1 like in the original scheme,’ says Napier. All remaining ducts not being used – which Napier describes as ‘a lot’ – will be closed up.

Professors' studios west wing, on the top floor at The Glasgow School Art. Credit: Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images

As with Mackintosh’s original scheme, the system is full fresh air; unlike the original, however, Harley Haddow’s solution will include heat recovery. Heat will be recovered from the exhaust air by connecting the original extract ducts to an existing plenum duct, located above the ground-floor corridor ceiling. This duct is then routed back to the basement, via the old steam-boiler chimney, from where it will pass through the thermal wheel heat recovery units installed in the space previously occupied by the steam heating coils.

Harley Haddow’s scheme supplies just enough heated fresh air for ventilation and to assist with space heating. The main heating will be provided by underfloor heating or an LPHW radiator system. In a nod to the original, for example, the entrance foyer will have underfloor heating. With Mackintosh’s warm-air ventilation system, the foyer was located directly above the basement space containing the steam boiler and heating coils.

‘The philosophy was that the floor would be heated from below, by heat given off by the boiler and hot coils,’ says Napier. Now, with the boiler no longer in place, a new underfloor heating system will warm the floor instead.

The heating strategy

Underfloor heating will also be installed in the restored library. The original building design had the library heated using the warm-air system alone. However, letters from the School to the original contractor indicate that this solution did not work as intended and radiators were installed to improve comfort, and then the warm-air system was later abandoned.

Needless to say, radiators will not be a feature of the restored library. Instead, an underfloor heating system – installed beneath a new floor – will heat the space. Additional warmth will be supplied by a fan heater – a duct mounted fan, low temperature hot water heating coil and air filter assembly – concealed in the basement service shaft, and ducted up to the room using the existing 1910 brick air ducts and grilles that previously served the library. The heat source for the fan heater is from the building’s heating system.

A similar solution of underfloor heating and concealed fan heater will be used to heat the Mackintosh Room. This is situated on the east gable, directly opposite the library in the west, and is often referred to as the ‘Mack Room’. It was named on Mackintosh’s drawings as ‘Design Room’.

The quest for originality does not stretch to the use of coal, however. In a much more environmentally friendly solution, heat for the Mackintosh building is now piped from an adjacent building containing gas- and biomass-fired boilers.

Again, Mackintosh’s forest of timber ducts are a key part of the refurbishment. ‘The timber ducts that run up through the building are now being used as routes for new power and communications cabling, along with pipework for a new mist fire-suppression system,’ says Napier.

‘And, of course, we’ll be fitting the ducts with fire dampers and fire stopping.’

3D visualisation: section through west wing (including the library). Credit: SSV, Glasgow School of Art