Credit: iStock/Prawat

In June, the UK experienced its hottest temperatures since the 1976 heatwave, when the mercury hit 35oC in Southampton.

Heatwaves of this nature are no longer a thing of the past, and temperatures – especially in cities that suffer the urban heat island effect – are set to rise.

Many factors contribute to overheating risk in new or refurbished homes, including: high proportions of glazing; thermally insulating and single-aspect designs; community heating systems; and inadequate natural ventilation strategies. Buildings that cannot dissipate heat gains are also at risk.

The health and wellbeing impacts of overheating can be significant for residents, resulting in stress, anxiety, sleep deprivation and even early deaths in heatwaves, especially for vulnerable occupants. The situation is predicted to get worse. The Committee on Climate Change estimates that deaths arising from overheating could rise from 2,000 per year in 2015 to 7,000 per year by the 2050s.

The way people experience temperature is subjective too; it can depend on what they’re doing, how they’re dressed, their health and fitness, and whether they are male or female.

CIBSE’s new technical memorandum aims to address the complex way buildings respond to external temperatures and present the industry with a standardised methodology to assess overheating risk. The authors of TM59 Design methodology for the assessment of overheating risk in homes believe it should become an essential item in the designer’s toolbox.

The methodology

TM59 methodology shares its first criterion with that of the earlier TM52 The limits of thermal comfort: avoiding overheating in European buildings – the percentage of hours that cannot exceed the target temperature, based on the running mean. It applies to all occupied spaces. The second criterion is CIBSE Guide A’s number of hours exceeding 26oC in bedrooms at night – the temperature above which research shows sleep patterns are disturbed.

Also contained in TM59 are other input parameters for assessing overheating, including prescribed occupancy profiles, internal gains and window-opening profiles.

TM59 requires designers to run simulations based on 24-hour occupancy. ‘Lifestyles change – it is now reasonable to assume that people might be at home during the day, so the design needs to be fit for purpose and acceptable at all times,’ says TM59 co-author and founding partner at Inkling, Susie Diamond.

The methodology is intended to be a robust test of the architecture and design, not how the building will be occupied, adds Dr Anastasia Mylona, CIBSE research manager. ‘If a building passes under the conditions specified, it will thermally perform independent of occupancy profiles or, indeed, if people use the building during the day.’

Mitigation strategy

The TM urges designers to carry out noise and pollution assessments before assuming a building will be naturally ventilated. Diamond says: ‘If windows need to be opened as part of the mitigation strategy, but the air quality is bad or it’s a noisy neighbourhood, this could affect how the building is ventilated. The point is for designers to understand limits better, and be mindful not to contradict acousticians’ recommendations.’

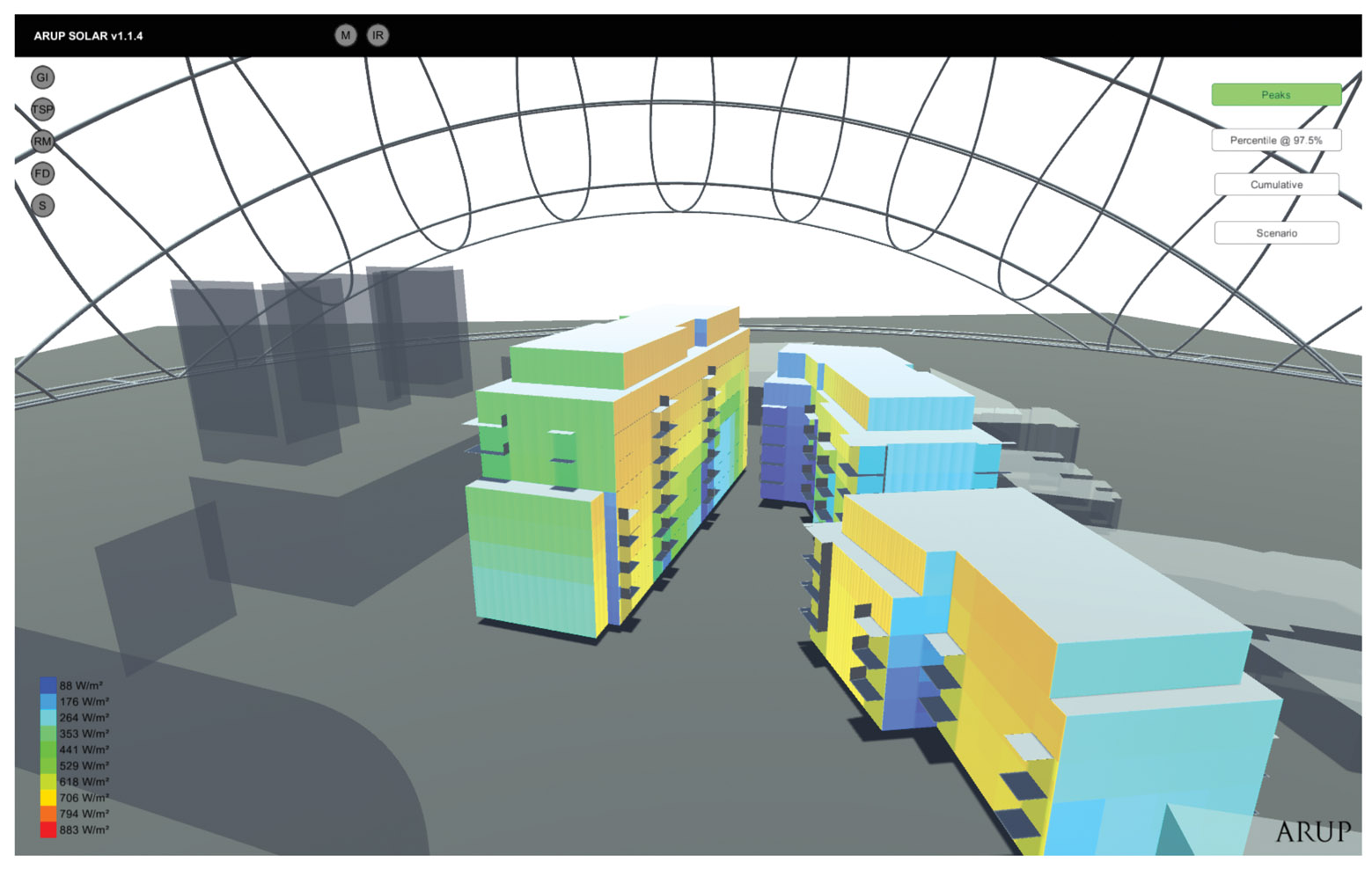

The methodology has been tested by a team of industry modellers, who not only tested a standardised model in IES, TAS and Energy Plus software, but also used it on live residential projects. Two such schemes are Arup’s Watermeadow Court – a development of 219 apartments across three buildings – and Edith Summerskill House – a 20-storey tower comprising 133 social rented and affordable apartments – both being developed in a joint venture between Stanhope and the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. An initial research project to investigate and develop a consistent methodology for overheating was funded by Arup and Stanhope, which supported the testing of its residential projects during the development of TM59.

After carrying out tests on a sample of Watermeadow Court flats, Arup found that the quantity of glazing on certain façades needed adjusting to help reduce overheating. ‘We proposed a few alterations that wouldn’t change the architectural intent, but would improve the worst performing flats,’ says Chris Eliades, mechanical engineer at Arup.

This involved introducing more solid elements on the façade to reduce glazing areas, as well as using side-hung – instead of top-hung – windows and doors to maximise the openable area and improve ventilation. They also agreed – with both architects Darling Associates and daylighting consultants – different g-values to achieve a good balance between daylight and solar gains.

Additional measures included: highly insulated pipework in corridors; insulated heat interface units; ventilated utility cupboards; LED lighting; and installing mechanical ventilation heat recovery units, with summer bypass and boost mode, to increase the ventilation rate when required.

Despite being mechanically ventilated, the development was tested as a free-running building with positive results. West-facing, single aspect and some top-floor apartments showed a higher risk of overheating.

At Edith Summerskill House, the façade orientation was carefully thought through by architects Henley Halebrown, which had created dual aspect apartments with corner living spaces.

Eliades says, following Arup’s intervention, side-hung windows with Juliet balconies were incorporated, achieving a 33% ‘openable’ glazing area, while internal blinds were included on large, fixed window panes.

Both projects show that TM59 allows designers to achieve an improved design, even in central London. ‘It makes you think of all the different aspects affecting overheating at the early design stage,’ he says.

He says the architects, on both projects, were amenable to altering their designs. ‘If you highlight the problem and offer a solution – without changing the overall design intent – they are not opposed to it.’

A key aspect in TM59 is the use of blinds. If they are part of the mitigation strategy, they must be allowed for in the model, and then installed. ‘Designers might be using shading in their calculations at the design stage but – if the developer fails to incorporate shading devices – it makes a huge difference as to how the building will perform in a heatwave,’ says Mylona. The kind of blinds used must also be specified, adds Diamond. ‘They must then be paid for, and installed, because owners might not put them in.’ The overheating report must also produce dynamic modelling results both with and without blinds, indicating how significant they are in generating a ‘pass’ result. Why shading is key

But it’s important to do this at the early design stage – before the architects have finalised their drawings, says Marguerita Chorafa, principal building physics engineer at Aecom. ‘At that stage, you can still influence the design and help the architects improve the façade, orientation or general layout of the development but, if the building has been submitted for planning, the façade is fixed, so shutters or other external shading devices are harder to adopt.’

Chorafa says the Greater London Authority is currently reviewing its guidance, with a view to adopting TM59 methodology into its energy planning guidance. Other local authorities are expected to follow suit.

The team of modellers will now collate its results from applying TM59 on new projects and come up with rules of thumb for aspects of design that could help prevent overheating.

“It has been a very encouraging process of industry coming together to produce something obviously needed in the sector”

There’s also scope for MVHR manufacturers to improve product ventilation rates without creating excessive noise, and to create efficient bypasses, says Diamond, while window manufacturers may find new solutions for flexible openings that are more acoustically attenuated.

Mylona says: ‘It has been a very encouraging process of industry coming together and volunteering time to produce something that was obviously needed in the sector.’

The guidance is timely. In 2017, we have had hotter temperatures than CIBSE’s ‘extreme’ 1976 weather file, and this trend is set to continue. ‘Although the 1989 weather file – which TM59 recommends for London – is a robust test, this summer reminds us that it can get warmer, so testing more extreme weather files to mitigate future climate is something designers must consider more and more,’ says Chorafa.

- TM59 can be downloaded for free at cibse.org/knowledge For details of CIBSE’s new weather data sets visit cibse.org/weatherdata