The factory floor at SES Engineering Services’ Prism facility, on the outskirts of York, is quiet, bright and clean. Workers calmly assemble a range of roof pipework modules and utility cupboards, while engineers test completed plantrooms for leaks.

It’s far removed from the experience of M&E installers on many building sites, where they vie with various trades for access to plantrooms and vertical risers, in a huge game of construction sardines.

SES Engineering Services business director, Steve Tovey, says the controlled factory environment offers benefits to the M&E design and installation that onsite construction cannot match.

‘The main contractor’s critical path is being attacked all the time by MEP [mechanical, electrical and plumbing] issues on site,’ says Tovey. ‘The real benefit is how many hours we take off site, into a factory. It leads to an improvement in quality, health and safety, and certainty of delivery.’

Each new worker at Prism can learn the core skills required in 12 weeks. For each type of system assembly, Prism provides simple pictorial guides

Around £500,000 of M&E work passes through the Prism facility every month. Plantrooms, plant skids, corridor pipework modules, roof pipework modules, and utility cupboards are built on assembly lines. Utility cupboards, in particular, have taken off in the past five years, says Tovey, as landlords are keen to separate theirs and their tenants’ billing.

Landmark projects include the Queensferry Crossing and the residential conversion of the Gasholders at King’s Cross, where wedge-shaped modules were built off site.

SES has also just completed an £18m project to prefabricate services at a £75m food and health research laboratory for the Quadram Institute in Norwich.

Convincing developers of the benefit of offsite construction is not always easy though. ‘Developers want everything faster and cheaper, and they aren’t always interested in the offsite solution because they don’t see the tangible benefits,’ Tovey says.

‘If you get the MEP contractor in early, you can work in partnership and design the services efficiently from day one.’

The firm’s managing director, Jason Knights, says it is better to win a job with a main contractor, as you can work through the design with them at the beginning, using building information modelling (BIM).

‘We help contractors win projects,’ he says. ‘In construction, the difficult things that can’t be solved tend to get pushed along. You’re forced to get it right with BIM.’

Knights says that if the M&E contractor is tendered separately – they would have much less time to design. It forces services designers to have conversations with architects about the amount of space services need, he adds.

‘They have to make decisions about their designers early in the process. That’s a massive tangible benefit. Prefabrication can cost more money, but we can install services in a tenth of the time. The tangible saving is the improvement in health and safety, quality and programme.’

One of the big drivers for prefabrication is the skills shortage in construction. Specific skills are not required to assemble services at Prism, and each new worker can learn the core skills required in a 12-week programme, which includes instructions on basic pipe-jointing techniques, pipe cutting and bending, trunking installation, and understanding drawings. For each type of system assembly, Prism provides simple, pictorial guides for workers.

The number of hours saved going on site is a key metric for SES; annually, it takes around 100,000 working hours off site, but it wants to double this figure within five years.

Tovey says onsite workers only work 40-50% of the time. ‘In projects up to eight storeys, for example, there is no requirement for a lift, which means workers have to spend time getting to each floor. With a prefabricated vertical riser, we can just drop it in with a crane,’ he says.

‘By taking work hours off site, the contractor can also save the cost of supplying services to onsite workers, such as toilets, toolbox talks, safety inductions and welfare facilities,’ says Tovey.

BIM and prefabrication

Prism would not have been possible without the adoption of BIM by SES, say Tovey and Knights. Original drawings are sent to SES’ in-house BIM coordinators who will talk to project engineers before creating a BIM model.

Tovey believes people are not used to designing for a manufacturer. ‘The software modellers are not engineers, so you need a BIM model to explain how you access and tighten a joint, for example,’ he says.

Once the drawing has been made ready for manufacture in BIM, it will pass through an approval process, which includes consultants.

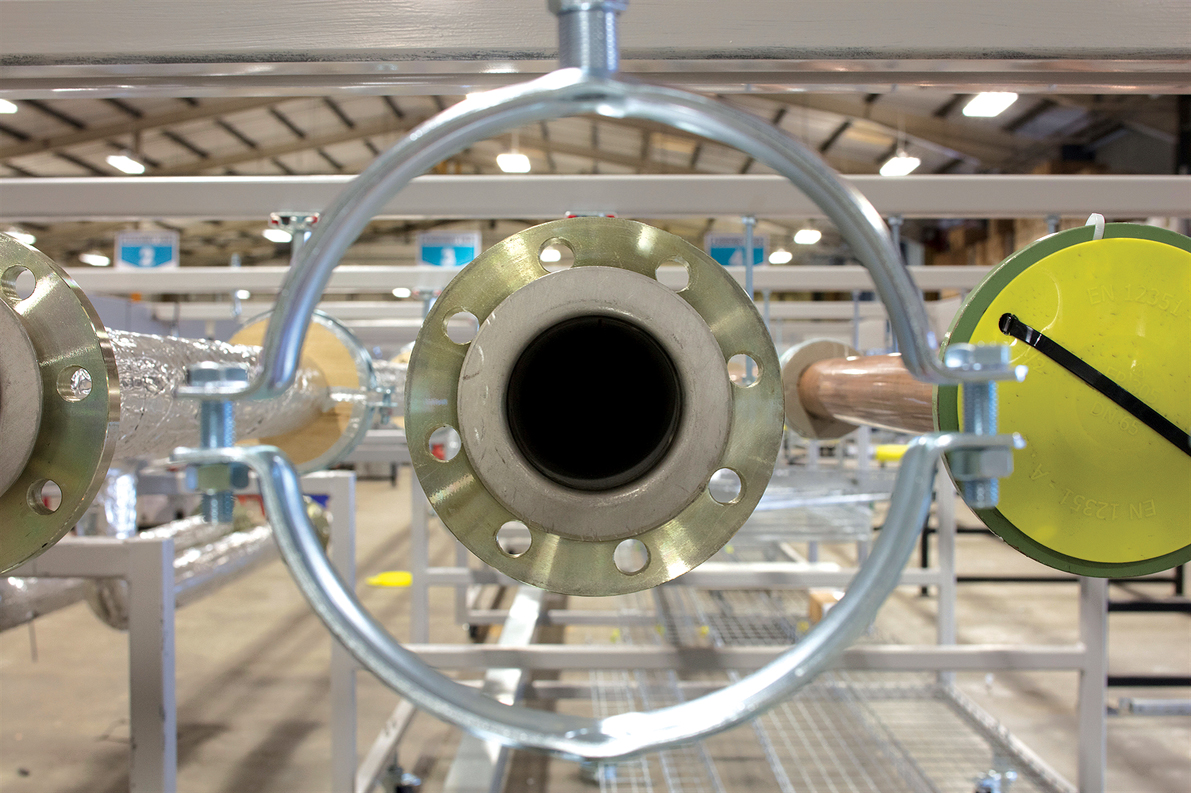

A utility cupboard assembled at Prism

Lewis Jones, Prism general manager says this process can make up a large proportion of the time taken for designs to be manufactured. ‘A plantroom might only take six weeks to build, but the approval process, logistical arrangements and preparing the building might take a further 10 weeks. If the plantroom is included as a manufactured product in the original design, you could reduce the programme by 10 weeks.’

Tovey says the products manufactured at Prism involve many in the supply chain, from structural to M&E engineers. ‘With better collaboration, the industry has the opportunity to improve quality and reduce programmes,’ he says.

‘Take digital collaboration for instance: what software are suppliers going to use? We get it passed to us in lots of different formats and it takes time to coordinate the drawings.’

Tovey believes understanding of offsite manufacturing is patchy within the industry. ‘People talk about offsite, but don’t always do it. The idea that you sit and plan the details of a bathroom or services distribution is quite alien to some,’ he says.

‘Clients often like to see a concrete frame being built to show progress, but that doesn’t get you any closer to the end of the project when the last thing you do is turn on the lights.’

SES is keen to boost the amount of services that are fabricated. Knights is aiming to increase annual work at Prism from around £7m to £20m, as well as widen the product range. He is also aiming to work on more prefabricated projects for parent company Wates, which purchased SES in 2015.

‘The whole basis of our approach is to reduce labour on site, which reduces the exposure to bad quality. We try to prefabricate up to 30% of services on each job,’ he says.

‘Prefabrication brings you value and certainty of programme. I always ask, why not prefab?’

The Quadram Institute

SES Engineering Services recently completed an £18m contract to deliver mechanical, electrical and plumbing services to a £75m food and health research laboratory in Norwich, the Quadram Institute.

The building comprises clinical laboratories and research environments that require strictly regulated, airtight conditions. Using BIM and prefabrication, SES delivered 36 plantroom prefabricated AHU valve arrangements, four plantroom pump skids, and 164 pipework and electrical containment modules. In addition, six ductwork risers, four pipework risers and three electrical risers were installed, each with platforms four floors high.

‘This project has been delivered with offsite methodology at its core and, critically, the project sequence would have been far more challenging without it,’ says Jason Knights, managing director at SES Engineering Services.

Knights says BIM and prefabrication enabled SES and the main contractor to work with the design team to maximise the offsite strategy. The coordinated design ensured clashes were detected at an early stage, resulting in less redrawing, and fewer snags and defects on site.

Prefabrication also meant fewer tradespeople driving to site, and fewer deliveries of materials, as well as better quality control on site. Plant and equipment was tested in the factory before installation, says Knights, which meant problems were identified off site.

The building’s scale – and the logistical challenges of a confined site – would have made producing modules on site extremely difficult, adds Knights, who says offsite was the only sensible option from day one.

The MEP package for the Quadram Institute was large for the local market, which gave SES the challenge of securing the necessary labour at the right time.

‘Moving some of this construction off site helped temper these resource requirements, and give reliability to achieving a challenging programme,’ Knights says.