Necessity has driven the Orkney Islands to embrace electric heat pump technology. Credit: iStock.com – Nicola Colombo

The Scottish government published its Heat in Buildings Strategy in October. Similar to that published in England, the document has identified the contribution heat pumps will make, as a ‘tried and tested measure’, to Scotland’s fight against climate change.

Scotland is ahead of the rest of UK when it comes to installing small-scale renewable schemes, with the remote Orkney Islands leading the way. According to MCS, the certification body for renewables, one in five properties on the Islands has some form of small-scale renewables.

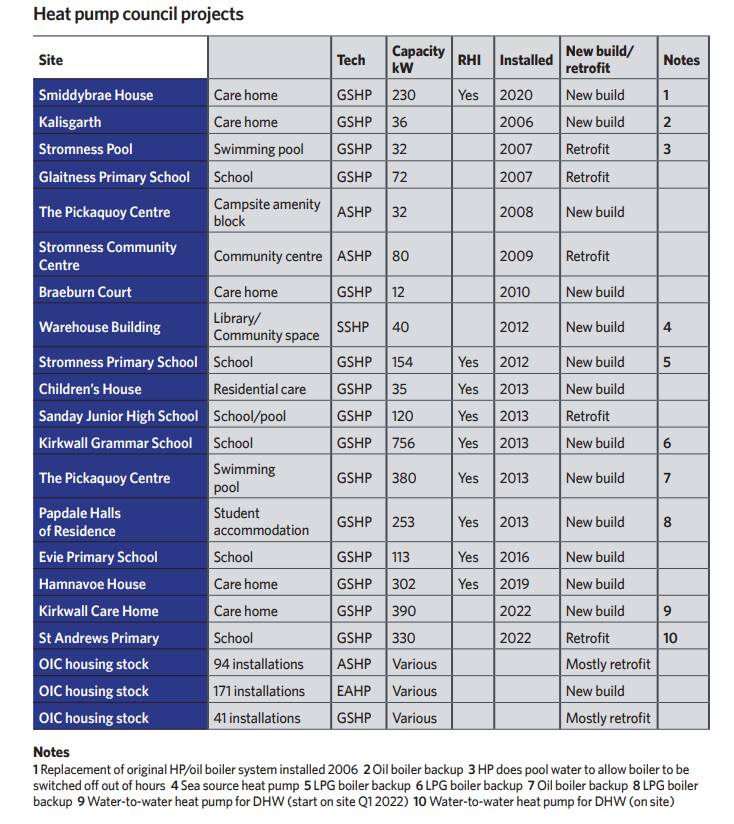

More impressively, for the past 12 years Orkney Islands Council has been pioneering the use of large-scale renewables through its commitment to heating council buildings, including offices, schools and care homes, using heat pumps. In that time, the council and its consultants have completed 16 schemes, and gained valuable experience of how best to use heat pumps on both new-build and retrofit projects.

Alistair Morton, energy and utilities officer for Orkney Islands Council

Necessity has driven the Islands to embrace electric heat pump technology. ‘Orkney is off the gas grid, so we can heat our buildings with either electricity or oil-fired boilers,’ says Alistair Morton, energy and utilities officer for Orkney Islands Council, and the person responsible for implementing the council’s Carbon Management Plan. ‘Because of the council’s commitment to reduce carbon emissions, we’ve been going down the heat pump route for all our new-build properties for over a decade,’ he adds.

The council’s first venture using ground source heat pumps (GSHPs) was on two new-build care homes: the relatively small development on the island of Westray, and Smiddybrae House in Dounby, on the Orkney mainland. Both were designed with back-up oil-fired boilers because ‘no-one trusted the heat pumps to deliver’, Morton recalls.

Following on from the care homes, the council then opted to use ground source heat pumps on a series of larger, new-build schools projects: Kirkwall Grammar School (including an attached theatre and fitness centre); Stromness Primary School; and Papdale Halls of Residence. Unusually for Orkney, in addition to heat pumps the schools also incorporate liquified petroleum gas (LPG) boilers to provide high-grade heat for the hot-water coils in air handling units, and to top up the temperature of the hot-water systems.

LPG was used in preference to oil because the council was aiming for a Breeam rating of Excellent. The success of the schools project subsequently resulted in GSHPs being used on The Pickaquoy Centre for sport and leisure. More recently, the council has installed a seawater heat pump to take heat from the sea at the adjacent harbour, to heat its new offices and public library in Stromness.

One thing we have learnt is the importance of thermal testing the ground to ensure we design the ground array based on actual data

The key lesson the council has learnt from its GSHP rollout has been the need to test the thermal response of the ground. The Smiddybrae House care home project was one of its initial GSHP schemes. Rule-of-thumb calculations were used to determine the number of boreholes needed for the scheme.

However, after two years of continuous use it became apparent the array was too small when so much heat had been taken from the ground that it had started to freeze, causing frost heave. Now, thermal response tests are carried out as part of the scheme design. ‘One of the main things we have learnt is the importance of thermal testing the ground to ensure we design the ground array based on actual data,’ Morton explains.

In contrast to Smiddybrae, on Hamnavoe House care home, in Stromness, the ground array initially appeared to be generating too much heat. According to Morton, this was because the heat pump’s output had been worked out based on the depleted conditions found in the boreholes at the end of their 20-year design life.

‘We’d sized the heat pump based on water entering the array at -5°C, returning at 0°C, when in fact it was going out at 5°C and returning at 8°C,’ he says. ‘Ensuring we sized the plant for the initial borehole output was a learning point,’

The council is also hoping that, by the time the scheme has been running for 20 years, heat pump technology will have evolved to the point where it will be able to replace the current units with heat pumps that will work effectively at the depleted, lower temperatures of the boreholes with a good coefficient of performance. ‘We want these boreholes to last for 50 years,’ Morton says.

Monitoring installations has also become more sophisticated over time. Morton admits the initial schemes had insufficient meters and sensors. Newer projects, particularly those installed under the Renewable Heat Incentive initiative, have heat meters and sensors. The council is also monitoring performance of the ground loop.

Case study: Retrofitting heat pumps in Sanday Community School

Sanday Community School is a junior high school catering for pupils aged three to 16 years. It also serves as a community centre, with facilities such as a meeting room, swimming pool and fitness centre for use by pupils and local residents.

Built in the 1960s, the 2,000m2 school incorporated a poorly insulated flat roof and large areas of floor-to-ceiling, single-glazed, steel-framed windows. An LTHW radiator system, run from two 250kW oil-fired boilers, kept the school warm using generously sized radiators to offset the heat losses through the large expanses of single glazing.

Over time, the thermal performance of the school’s envelope has been gradually improved. The flat roof was covered in a thick layer of insulation that was then hidden beneath what Morton describes as a ‘crinkly tin’ pitched roof, complete with a ventilated roof void. The windows were also replaced with semi-glazed panels featuring an insulated-panel lower section and a double-glazed unit above. Insulation was also added to the brick cavity walls.

By 2010, the oil-fired boilers, operating at 82°C/71°C, were on their last legs and the decision was taken to replace them with heat pumps. To keep the heating system running while they were installed, a new plantroom, incorporating a pre-insulated 10,000-litre thermal store, was constructed at the school before the oil boilers were decommissioned.

The buildings improved insulation meant the initial radiator design was now significantly oversized and they were able to reuse the original radiator system and pipework with the 50°C/35°C flow and return temperatures. The large thermal store enabled the buildings to head up in one-third of the time previously taken by the oil boilers.

Sanday heat pump

Alongside ground source and sea source heat pumps, the council has used air source heat pumps (ASHP) with limited success on a couple of housing schemes. ‘There’s a lot of salty water in the wind, so we have to be very careful with the spec for air source heat pumps; we get the pumps and coils treated for maritime conditions, but it’s the external casing that we’ve found soon corrodes and falls to bits, exposing the nice shiny heat pumps,’ says Morton. ‘The first batch [of ASHPs] we put in had to be replaced within a couple of years because of case corrosion.’

In addition to promoting corrosion, the wind also draws heat from the buildings. Orkney’s temperate maritime climate means that temperatures average 5°C in winter and 15°C in summer as a result of the warm Gulf Stream. The Islands’ relatively consistent temperatures are accompanied by almost continuous wind, which averages 7m.s-1 (13.5 knots) over a year.

‘The wind strips the heat out of the buildings, so we have to design them with minimal envelope penetrations,’ says Morton. ‘Extract fans can really cause problems, so, in new builds, we put in centralised MVHR units with one intake and exhaust.’

The relentless wind is the reason Orkney is dotted with wind farms, which result in it annually exporting more electricity than it consumes. Interconnectors transfer the wind-generated power to the mainland grid. Bizarrely, this is then sold back to the Islanders with a surcharge of 2p per unit. ‘We end up paying 2p per unit more for electricity than the rest of the country,’ Morton explains.

He admits that, if Orkney did have access to the gas grid, he probably wouldn’t be using heat pumps for most schemes, because the cost of electricity would make them uneconomic. ‘Most of the time, we propose heat pumps on the basis of lower carbon emissions, but the bottom line is that, currently, electricity is at least three times more expensive than oil,’ he says.

The islands' relatively consistent temperatures are accompanied by almost continuous wind

Another frustration for Islanders is that insufficient grid capacity means that, when the wind is blowing hard, wind turbines have to be shut down to limit electricity generation. It is a situation that is set to change under the ReFlex project, which will develop an electricity smart grid.

Under the scheme, electric vehicle chargers will be switched on, and heat pumps will top up heating systems in public buildings and homes with cheap electricity when the grid starts to become overloaded. This will enable the turbines to keep running.

Meanwhile, the project currently occupying Morton is the refurbishment of the heat pump system at Smiddybrae House, the council’s first heat pump scheme. This involves the installation of a new borehole array and replacement of the heat pumps.

And, 12 years after the heat pumps were first installed in the care home, the council has removed the oil-fired boiler backup. ‘We’re now confident we can meet 100% of the heat load using heat pumps,’ says Morton.

Scottish support

The Scottish Net Zero Public Sector Buildings Standard is a voluntary standard to support public bodies in meeting their net zero commitments for their new-build and major refurbished infrastructure projects.