York Guildhall, on the River Ouse

The Guildhall is a collection of some of York’s most historic buildings: a complex of Grade I, II and II*-listed properties built around a 15th-century Guild Hall and situated on the north bank of the River Ouse.

It served as the city’s seat of governance for more than 600 years, but when York City Council relocated, it wanted to refurbish the historic complex and turn it into a digital hub for the 21st century.

Together, architect Burrell Foley Fischer and SGA Consulting set out to deliver the council’s vision.

The interior of the 15th- century York Guildhall

The project team

Client and project manager: City of York Council

Architect: Burrell Foley Fischer

M&E consultant: SGA Consulting

Structural engineer: Arup

Quantity surveyor: Turner & Townsend

Main contractor: Vinci Construction

M&E contractor: Wheatley M&E Building Services

Alongside the creation of the digital hub, the project involved the refurbishment of the listed elements of the scheme to improve accessibility, occupant comfort and energy efficiency. It also included a new office extension and riverfront restaurant at the side of the complex.

The first time I went to the site, I took one look at the river and said ‘of course, we’ve got to use this

The scheme’s numerous listed elements made for an extremely challenging refurbishment. Except for the listed cast iron radiators in the Victorian council chamber, all of the existing building services had to be replaced, as they were long past their prime. ‘We started by asking what interventions we could make to the listed buildings and then set about working out how to deliver these in the best possible way,’ says Bart Stevens, a director of SGA Consulting.

some materials were transported by river

The building’s location, adjacent to the River Ouse, made a river source heat pump (RSHP) the obvious solution to heat and cool the building. ‘The first time I went to the site, I took one look at the river and said “of course we’ve got to use this”,’ recalls Stevens.

Permission to use the river was obtained from the Environment Agency and the Canal & River Trust, and an unobtrusive route for the abstraction and discharge pipework was devised from the basement plantroom to the river.

Waterbourne logistics

In addition to providing a source of free heat, the proximity of the River Ouse proved beneficial during the refurbishment works. The Guildhall’s location, in the centre of medieval York, made it difficult to get construction materials and equipment to the site and to remove waste from it.

Main contractor Vinci Construction overcame this particular challenge by using the river to transport heavy equipment and materials to and from the site by barge. Even this solution was not without its difficulties, however, because the river levels can rise by up to 5m after heavy rain in surrounding hills. At such times, deliveries to site were delayed because Vinci’s barge was unable to pass beneath the town’s bridges.

Fortunately, building services contractor Wheatley M&E Services was able to bring its materials in by land, without the need of the river, with the ‘exception of transporting the heat pump to site’, says Stevens.

Under the new scheme, 110kW of simultaneous heating and cooling is provided by a two-circuit, reverse-cycle RSHP. To optimise its efficiency, the heating circuit runs at 50oC flow/45oC return, while cooling is at 6oC flow/12oC return. The RSHP is also designed to recover heat if areas of the building require simultaneous heating and cooling.

Pipes taking water from the Ouse to the river source heat pump

A pragmatic fabric-first approach was adopted by SGA Consulting in developing the servicing strategy. Using the heat pump to service the new office extension and restaurant was relatively straightforward, because its fabric thermal performance exceeded Building Regulations minimum. However, the listed status of many existing elements and spaces meant opportunities to improve fabric thermal performance were limited. This had a major impact on how and where the heat pump-derived heat could be used.

The office extension and riverfront restaurant

The lower temperature of the heat pump heating circuit made it ideal as a heat source for underfloor heating, because the large floor area helps compensate for the lower temperature of the emitter. The heat pump is also used to supply heat to fan coil units (FCUs) in some of the office spaces. These incorporate oversized heating coils to compensate for the circuit’s lower flow temperatures.

Operating in reverse mode, the heat pump uses river water, extracted at up to 22oC and returned at 25oC, to also provide chilled water to the FCUs in south-facing river frontage rooms. ‘These rooms required cooling as well as heating, so we were justified in replacing the existing radiators with modern FCUs in these rooms,’ explains Stevens.

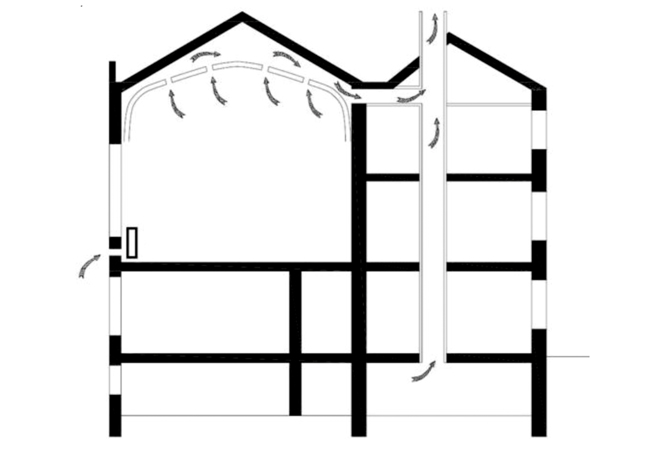

SGA Consulting has resurrected the original Victorian ventilation system to help alleviate stuffiness and overheating in the Grade II*-listed council chamber. The original building services proposal incorporated a series of FCUs to keep the council chamber comfortable. The units were to be placed outside the chamber and holes knocked through the wall to enable the units to circulate air. Historic England was not keen on the modifications, so an alternative solution had to be devised. ‘I said “I bet the Victorians had a way of ventilating the room”,’ recalls SGA Consulting’s Stevens. Low-level ventilation inlets had been identified in the external walls, hidden behind the cast iron radiators which also provide preheating to air entering the chamber. ‘After hunting around, we managed to find some holes in the ceiling, concealed behind rose-shaped bosses, which allowed the warmed air to exit the chamber and enter the roof space,’ says Stevens. In the roof, the ventilation system was originally linked into the flues from the coal-fired boilers using wooden ductwork . The system exploited the pressure differential caused by the upward flow of air from the boiler flues to induce airflow through the council chamber. The original council chamber ventilation system SGA Consulting set out to reinstate the original ventilation system, to enhance the airflow without any discernible visual impact in the council chamber. The coal-fired boilers are long gone, but the system still uses the original boiler flue. Because of fire regulations, the Venturi effect from the boiler flue had to be abandoned, so the airflow is now enhanced through the addition of a small axial flow fan. To further control airflow in the council chamber, motorised dampers (controlled on CO2 and temperature) have been added to the low-level intakes behind the radiators. Should they so wish, councillors also have the option of opening windows.Reinstating Victorian natural ventilation

SGA Consulting has also managed to hide four cooling-only FCUs beneath raised daises in the council chamber. This helps keep the space comfortable when the council is in session and the room is full of people. The consultant has also resurrected the original Victorian ventilation system in the chamber to further improve comfort.

A major benefit of using a RSHP to provide cooling was that it removed the need for an external air cooled condenser, which would have been noisy and visually obtrusive in this overlooked, congested and historic part of York.

The RSHP is housed on a plinth in the potentially flood-susceptible basement plantroom.

The River Ouse, which glides past outside – and sometimes inside – the Guildhall complex, is an asset and a liability. In addition to being a source of heat and coolth to the scheme, it’s a hinderance when the river floods. Heavy rainfall in the Yorkshire Dales and headwaters of the rivers that drain into the Ouse can raise its level by up to 5m. As a consequence, there have been frequent water incursions into the basement of the Guildhall complex, with the highest recorded level being 1.7m above the basement’s listed flagstone floor. To help withstand incursion of the river waters up to the year 2100, the armoured glass in the basement windows overlooking the river has been replaced with more robust glass. The existing flood doors have also been replaced with sturdier models, to help protect the subterranean space against the threat of flooding. Even with these measures in place, however, the basement is still vulnerable to water incursion, because water pressure forces groundwater up through gaps in the flagstone floor and into the basement plantroom. SGA Consulting has installed sump pumps in the space to help control the seepage, keeping the incision to a maximum depth of 20mm. ‘It is not ideal; the floor is listed and cannot be replaced, so we have had to keep the plant clear of the floor by mounting it on 100mm high plinths,’ says Stevens. City of York Council also had concerns that, if York was to flood so badly that there was an electricity blackout, it would prevent the sump pumps from working. Increased resilience has been provided by installing an additional access hatch at high level, to enable an electrical supply to be provided to the sumps from an external generator. Space was found on the floor above for all the major electrical switchgear. All electrical supplies in the basement plantroom are routed at high level, dropping down to the plant. In addition, non-return valves have been installed on the foul drainage to prevent back-flow.Keeping the river out

Alongside the electric RSHP, the scheme also includes three new gas-fired boilers. These supply a conventional low-pressure hot water heating circuit at 80oC flow/70oC return to furnish the cast iron radiator circuit in the Victorian parts of the building, along with two domestic hot water calorifiers that serve the new kitchen and toilet blocks. The boilers also provide back-up heat to the heat pump circuit, should the heat pump fail.

‘We used the heat pump in all of the spaces where we could make it work, but the heat losses are so great in the Victorian areas, and the floor areas fixed, so we had to reuse existing cast iron radiators and gas boilers to provide sufficient heat,’ explains Stevens.

The new extension to York Guildhall

Heat losses in the 15th-century Guildhall were also particularly high. The building’s Grade I listing meant that it was too difficult to enhance the thermal performance of the solid stone walls and there were insufficient funds to add secondary glazing to the windows. The team was, however, able to hide additional insulation in the roof as part of the lead-replacement works.

Bomb damage during World War II meant that the roof, floor, and some upper walls of the Guildhall had either been rebuilt or replaced, so English Heritage permitted underfloor heating to be installed in the 7m-high space. Even so, heat losses were so great that the heat pump-supplied underfloor heat system alone was insufficient to keep the space comfortable. ‘The heat losses were too high and we were very limited as to the interventions we could make,’ says Stevens.

Boilers are used on very cold days because of high heat losses in the historic buildings

SGA Consulting’s solution was to supplement the underfloor heating with trench heaters concealed within the floor and connected to the higher-temperature gas-fired boiler circuit, for use on cold winter days.

‘When the outside temperature drops below 5oC, the trench heaters turn on,’ Stevens explains. As a consequence, trench heating will only deliver 12% of the Guildhall’s annual heating demand, with the rest provided by the heat pump circuit. ‘This type of mixed use shows how heat pumps can be used to provide heating to old buildings where the rate of heat loss would be too high otherwise,’ says Stevens.

Operational energy and carbon

Actual metered energy use:

- Electricity: 209,027kWh/yr, of which heat pump consumption is 21,349kWh/yr

- Gas: 167,376kWh/yr

- Heat pump output: 86,354kWh/yr

There is no onsite renewable energy because the planners would not permit their installation on the listed buildings.

After the scheme’s completion in 2022, SGA Consulting followed a soft landings regime for two years, to optimise performance of the building services. Lessons learned include:

- Keeping the Guildhall underfloor heating off on cool summer days because of the long time lag in delivering heat

- Turning off the heat to the domestic hot-water systems over weekends when appropriate

- Reminding the client of the two-speed control for kitchen ventilation.

The strategy to re-use a centuries-old building, revitalising it for use for future generations, achieved significant savings on embodied carbon emissions. Equally importantly, the project succeeded in securing the future of the Guildhall complex; the University of York is taking a long-term lease on the historic buildings to create a business hub for spin-off firms from the university. This will contribute to the city’s future and is proof that historic buildings can be refurbished and remodelled to meet contemporary needs.

With the challenges we face in renovating millions of existing buildings, the York Guildhall project shows what can be achieved

SGA Consulting’s approach to the project certainly impressed the judges at this year’s CIBSE Building Performance Awards, where the project won a host of awards, including Building Performance Champion.

The judges said of the scheme: ‘With the challenges we face in renovating millions of existing buildings, the York Guildhall project shows what can be achieved to deliver sustainable building refurbishment, minimise embodied carbon and deliver such a project with the most difficult site-access conditions’.