The Guinness Partnership’s Stead Street property in London, where the pilot project took place

Affordable homes provider The Guinness Partnership (TGP) is a major supplier of heat in the UK. It has 150 heat networks supplying more than 4,500 homes. In the past three years, TGP has focused on improving the performance of its heat networks in a bid to increase customer satisfaction and cut costs. ‘Our networks were significantly more expensive to run than we expected,’ says Victoria Keen, head of sustainability at TGP, ‘which meant we were exposed to the risk of financial losses.

‘A new approach was needed, and we spent a lot of time reviewing where we needed to change. To get better at being a supplier, we realised we had to think about how we acted as a customer when networks were being built.’

Procuring the right equipment and advice – and setting performance requirements for the supply chain – were key to ensuring the heat networks operated at the correct levels, says Keen. To understand why they were costing more to run than expected, TGP worked in partnership with energy consultants Guru Systems and FairHeat to measure the performance of a heat network at one of its developments in London’s Elephant and Castle. Funding for the pilot project at the 140-unit residential block in Stead Street was provided by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS).

Guru Systems installed smart meters and extracted real-time data from the system using its Guru Pinpoint software. For the first time, TGP could see how well the network was actually performing compared with predicted performance. This offered the partnership and its contractor a chance to identify any technical issues before properties were handed over to customers. ‘The commissioning phase is a critical period for performance testing, allowing issues to be identified early on so they are easier and cheaper to fix,’ says Keen. After the pilot, commissioning testing was rolled out to the rest of the Stead Street network.

The project ran against the backdrop of a government report that shows about half of the performance gap on heat networks is because of poor commissioning, with the other half down to poor design. Casey Cole, managing director at Guru Systems, said the data helped identify how much heat-network performance could be uplifted through commissioning, the cost of carrying out improvements; and whole-life savings for the project.

As part of its commissioning support, FairHeat carried out acceptance testing before the dwellings were occupied by customers. ‘The objective was to identify the causes of performance issues, and reduce short- and long-term risk to the network operator,’ says FairHeat managing director Gareth Jones. In the short term, Jones adds, the risks arise from costly revisits and poor customer experience, while – over the longer term – operators are exposed to financial losses because of expensive running costs, or having to subsidise higher-than-expected bills.

During acceptance testing, the team used performance data from Guru Systems’ meters to isolate areas of inefficiency, and work with the contractor to carry out in-depth site investigations. These threw up a number of issues in key risk areas, such as resident comfort, regulatory compliance, low efficiency and post-occupancy call-outs. If uncorrected, these would have resulted in dissatisfied residents and significant ongoing costs, with a raised probability of overheating, says Jones.

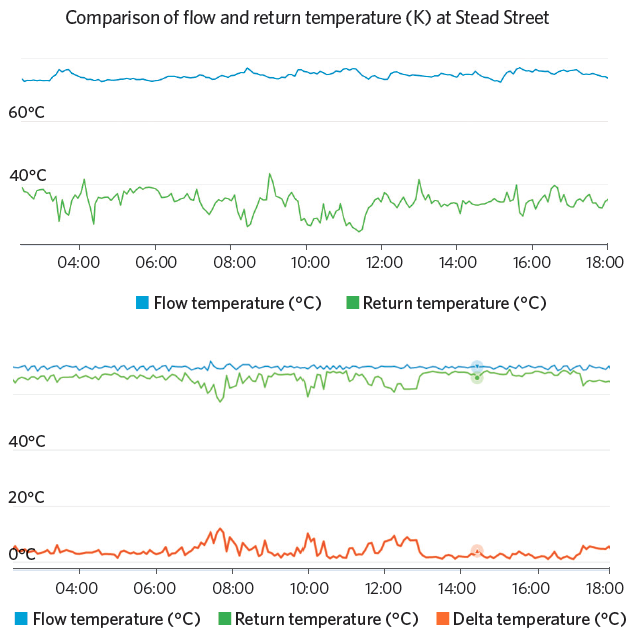

Working in partnership with the contractor, TGP implemented a testing regime and prescribed changes. This has resulted in average return temperatures dropping by 22°C, leading to a reduction in losses from the return pipework of around 75%.

The top graph shows the desired temperature differences between flow and return temperatures at Stead Street, while the one below shows an inefficient system (on another project) with a low flow-return temperature difference

The testing and changes will deliver an estimated saving of £2,000 per block, per year, equating to £65 per dwelling. This is in addition to significant cost reductions associated with avoided call-outs and management time, says Keen. ‘The detailed, diagnostic information provided by real-time network performance data was critical to identifying technical irregularities and the causes of inefficiency. It was vital that these issues were spotted at a time when our contractors were on site.’

Lessons learned – from Stead Street and other pilots – about the impact of data on network performance are now driving up efficiency across the heat-network sector, says Jones. ‘We started to see a familiar story. Suppliers had planned systems based on 70°C flow and 40°C return temperature, low losses and cool corridors, but soon saw from the data that they were getting something very different.’

Network performance levels were worse than expected, adds Jones, with corridors overheating and warm cold-water taps. ‘That is what drives up cost, impacts on customers, and exposes heat suppliers to risk,’ he says. Heat suppliers’ requirements of their contractors were not specific enough – and, says Jones, ‘there was no way to measure if they were being met’.

Cole adds: ‘There was a focus in the design stage to deliver abundance over efficiency – creating unnecessarily large networks that were costly to run. Big data has changed that, and allows providers to quantify performance and ensure standards are being met. Networks are performing significantly better – which is creating happier customers paying lower bills.’

Lessons learned

TGP has now developed a design guide that sets out clearly its core principles for heat networks. The guide is based on CP1 Heat Networks: Code of Practice for the UK, published by CIBSE and ADE, but gives specific objectives and performance criteria. It is supported by a commissioning guide.

TGP has also committed to carrying out acceptance testing on all properties before handover. ‘We even specify certain equipment choices,’ says Keen. ‘We wanted to know it can meet the performance standards we expect and is easy to maintain.

Many of the problems stemmed from the design stage, and retrospectively trying to rectify these was costly. ‘Designs were oversized and overcomplicated – leading to higher capital expenditure,’ says Keen.

‘The design and commissioning guides allow us to take the lead, so contractors understand the performance standards we want to achieve. In the main, they create a better working relationship, because there is clarity on all sides.’