Building energy modelling (BEM) has been an essential tool for engineers since the 1970s, supporting the design and operation of buildings by simulating thermal behaviour, energy use and system performance.

Traditionally, models have relied on physics-based methods, which remain indispensable for their interpretability and compliance with standards. More recently, reduced-order and data-driven approaches have been introduced to supplement these methods.

Now, a new wave of artificial intelligence (AI) is beginning to reshape how models are created, calibrated and applied.

A new paper, AI for building energy modelling: a transformation, published in Building Simulation, sets out how AI is beginning to alter BEM workflows.

Written by Tianzhen Hong, of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and Liang Zhang, of the University of Arizona, the paper highlights the opportunities for automation, speed and accessibility, while recognising the challenges of trust, data quality and appropriate use.

The acceleration of digitalisation in the built environment means vast volumes of data are now collected routinely, from smart meters and sensors to design records and open databases.

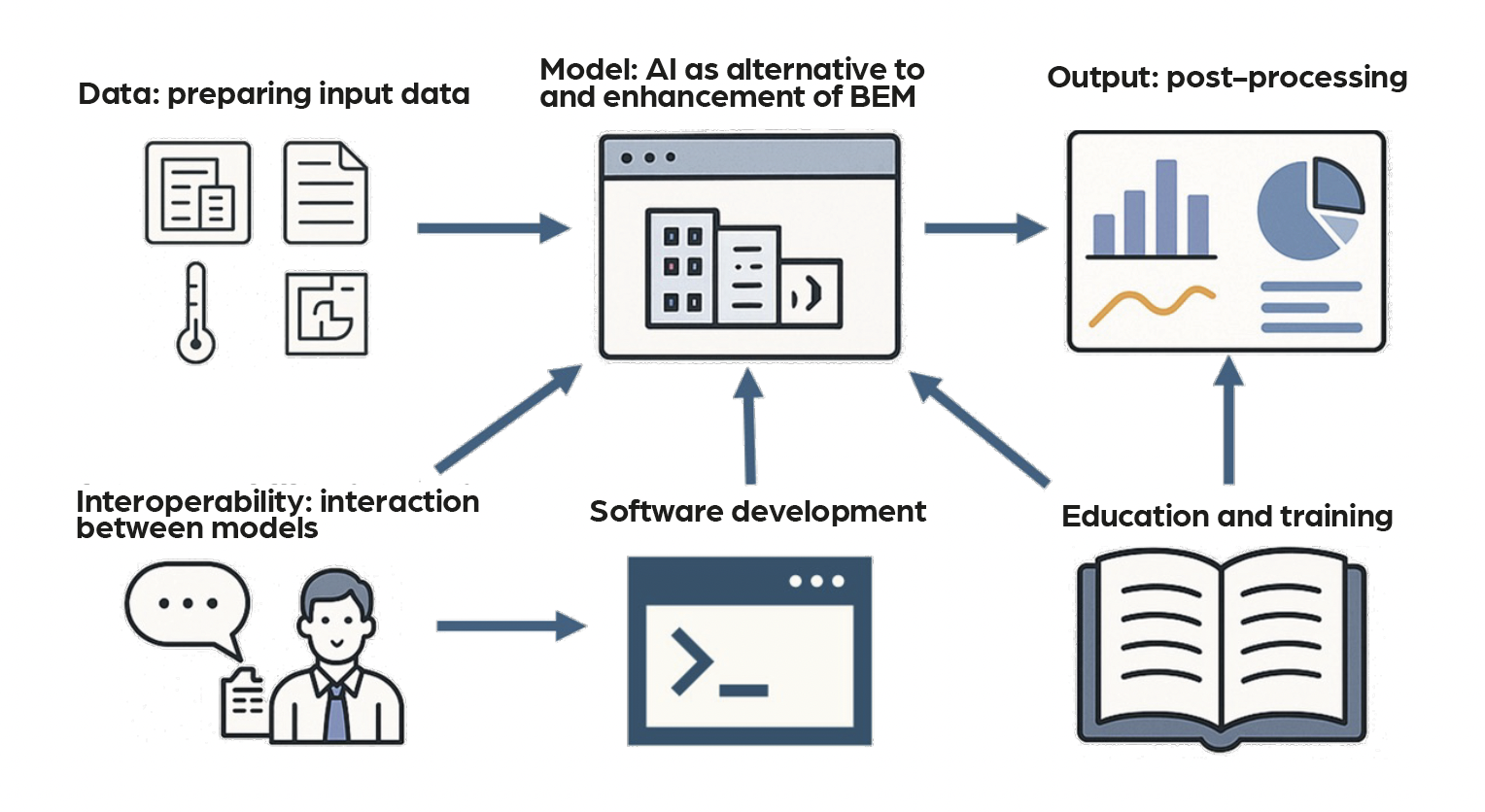

Overview of AI opportunities and applications across BEM. Credit: Hong and Zhang

At the same time, computing power has become more affordable and accessible. These trends, coupled with the rapid development of AI, are enabling engineers to rethink the way BEM workflows are organised.

Where once practitioners had to collect inputs manually, assemble models and parse complex outputs, AI offers opportunities to automate these steps and expand the scope of applications.

One of the most striking changes is in the preparation of input data. Traditionally, gathering building information required time-consuming site surveys, drawings or audits. AI methods such as computer vision and natural language processing can now extract characteristics from photographs, satellite imagery, lidar scans or planning documents.

Geometry, façade type, window ratios and rooftop HVAC systems can be identified automatically, reducing the cost and time needed to create models. AI also helps clean incomplete datasets and infer missing values, making them fit for simulation.

Model generation is another area in which AI is making an impact. Surrogate models and deep-learning networks can approximate the results of detailed simulations at a fraction of the computational cost.

Transfer-learning methods allow data from one set of buildings to inform models of another, increasing efficiency when information is limited. Large language models (LLMs) are emerging as particularly powerful tools: by translating natural language descriptions, spreadsheets or CAD drawings into syntactically correct EnergyPlus or Modelica files, they could make model creation more conversational.

Rather than laboriously constructing every object and reference, practitioners may soon describe design intent and allow an AI assistant to assemble a consistent, code-aligned simulation file.

CIBSE and ASHRAE's commitment to AI

CIBSE has already recognised the importance of this shift, launching an expert Artificial Intelligence Working Group to guide the institution’s response to emerging technologies, policy and ethics.

Its first task is to develop a formal position statement, before establishing a Special Interest Group open to members and the wider building services community.

Key areas under consideration include terminology, relevant legislation, ethics and professional guidelines – all vital to ensuring that AI is applied responsibly.

ASHRAE has also convened a Multidisciplinary Task Group on Generative AI, with Hong among its contributors, to coordinate research, standards and professional guidance. Together, these initiatives show that both institutions view AI as a strategic priority for the profession.

Simulation itself is being reshaped. Researchers are developing protocols that act as universal connectors between AI tools and modelling engines, enabling a more fluid, two-way interaction.

This opens up the possibility of rerunning simulations with alternative parameters or correcting errors through dialogue with an AI interface. Such developments could lower the barrier for new users and make simulation more accessible to multidisciplinary teams.

The analysis of outputs is another domain in which AI is proving valuable. Simulation generates vast volumes of time-series data that can be difficult to interpret. Generative AI can process these results to produce summaries, benchmark comparisons, and even narratives explaining performance trends.

Instead of wading through spreadsheets and plots, an engineer could query a model in natural language – for example, asking why fan energy peaks in spring or how a building’s cooling load compares with peers. This ability to turn raw data into actionable insight could embed modelling more firmly into decision-making.

By shortening learning curves and spreading modelling skills more widely, AI could prove transformative.

AI is also beginning to support software development and education. Code-generation tools can assist developers of BEM engines in testing and debugging, while AI-enabled assistants could help students and practitioners interpret error messages, learn best practice and understand complex workflows.

By shortening learning curves and spreading modelling skills more widely, AI could prove transformative.

Despite these advances, challenges remain. Data availability and quality are persistent issues, with many datasets incomplete or inconsistent, and privacy especially sensitive where occupant behaviour or energy use is concerned.

Trust in AI models is another barrier: outputs may be opaque, prone to error or hard to reproduce. Standards and benchmarks are lacking, making it difficult to compare approaches or verify claims.

Most importantly, clarity is needed on when AI should enhance physics-based modelling, and when – if ever – it can replace it. Physics-based methods still provide robustness, compliance and interpretability that data-driven models cannot match.

Looking ahead, several trends are emerging. Generative design assistants could propose efficient system types, control strategies or façade options tailored to climate and regulation, supporting performance-driven design from the earliest stages.

AI will not replace the expertise of experienced practitioners, but it will automate routine tasks, accelerate workflows and lower barriers for a broader community of users

Autonomous AI agents may soon execute entire modelling workflows with minimal human intervention, which would be particularly valuable at the scale of cities. There is also growing interest in domain-specific models such as BEM-GPT – smaller, specialised foundation models trained on building physics, standards and simulation syntax.

At the operational level, digital twins are likely to benefit from AI by combining live data with models for forecasting, diagnostics and optimisation.

For building services engineers, the implications are clear. AI will not replace the expertise of experienced practitioners, but it will automate routine tasks, accelerate workflows and lower barriers for a broader community of users.

Engineers will remain essential for ensuring responsible deployment, validating results and providing the domain knowledge that AI cannot replicate. At the same time, there will be a growing need for professionals conversant in both building physics and data science.

AI represents a powerful extension of the building energy modeller’s toolkit. By integrating new methods thoughtfully, the profession can enhance productivity, broaden participation and embed energy modelling more deeply into the design and operation of buildings.

The transformation is already under way – and those who embrace it early will be best placed to deliver the next generation of efficient, resilient and comfortable buildings.

Hong and Zhang’s full paper can be read here in the Simulation Journal