Cranmer Road won Project of the Year (non-domestic) at the 2023 CIBSE Building Performance Awards

I’m In the past two years, CIBSE has been reviewing entries to the Building Performance Awards to assess building performance across the projects, as well as the quality of the information provided. The review helps identify best-performing projects and where they sit against industry targets – for example, RIBA 2030 Challenge, LETI, emerging UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard – and against benchmarks for the existing stock.

The first review1 led to a new data entry form for the 2022 awards, to provide more clarity on the information needed, a clearer and fairer basis for judges to assess the entries, and more value to industry, as the submitted data can contribute to analysis.

Last year’s review2 led to further changes, requiring more information to be provided rather than being optional. Data on energy supplied by onsite generation (not just from the electricity and gas networks) was required, so that all projects have to submit enough data to assess the project’s total energy use.

Airtightness test results, where available, also had to be submitted. This recognises the importance of airtightness as a key building performance parameter and the fact that information is often available, as a test is carried out on new buildings and many extensive retrofits.

Bungalows retrofitted by the WSA with Swansea Council

Quality of the data

This year’s analysis confirms that the quality and scope of building performance data keeps increasing, through better gathering and reporting of the data, as well as through increased post-occupancy evaluation (POE) activities.

A lot of the ambiguity of past submissions has been removed from the forms – for example, on the type of floor area measurement, the time period covered by the meter data and whether it represents ‘normal’ occupancy and so on. Some uncertainty does remain, particularly around metering of onsite generation systems and batteries: the data being reported is often not sufficient to assess the building’s total energy use, or the data is inconsistent.

This highlights common issues with metering and insufficient checks on data quality as part of building performance evaluation. For example, do meters add up? What are the energy flows between grid, building, onsite PVs, and batteries? Some projects also had electric vehicle (EV) charging on site, often without sub-metering, which meant it was not possible to assess energy used by the building itself, out of the total.

What the data reveals

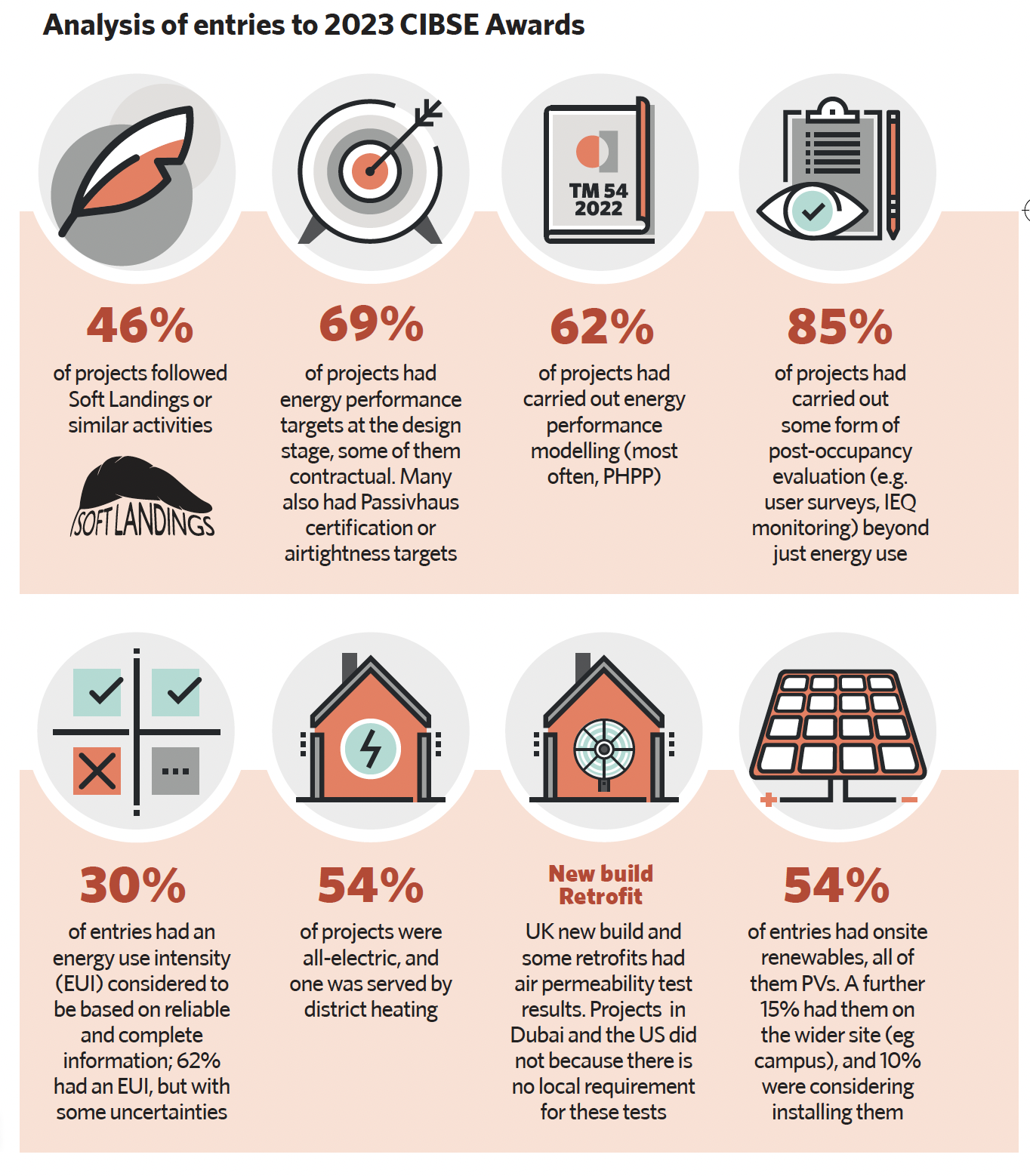

This year’s awards data shows trends in delivery processes and design solutions similar to last year, illustrated below.

As expected, projects set energy targets beyond regulatory compliance and paid attention to energy performance modelling, often using Passive House Planning Package (PHPP), both in domestic and non-domestic building projects.

They carried out POEs and, this year, there was significantly more attention to factors beyond energy use, such as indoor air quality, temperature monitoring, and interviews or surveys of building occupants. In design teams, the large majority of projects have ambitious airtightness and space-heating demand targets, most are all-electric, and most have onsite generation systems – in some cases deliberately producing more than the building’s annual energy use for export.

The two retrofit projects – with comparable uses pre- and post-retrofit and with energy use data pre- and post-retrofit – demonstrated energy use reduction of between 60% and 83%. Most projects had done some form of embodied carbon assessment, either of specific building elements or whole buildings.

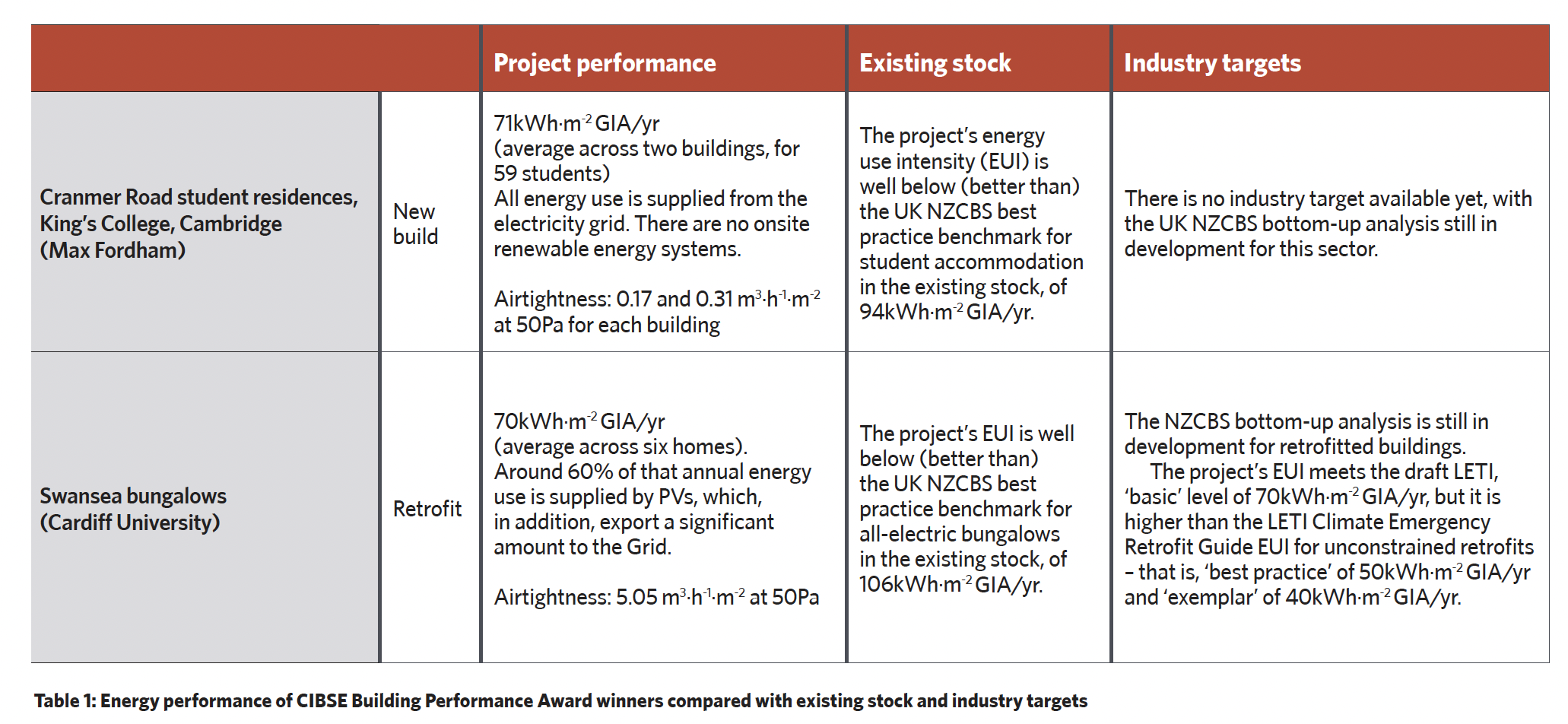

This year’s two Project of the Year awards winners – Cranmer Road, Kings College Cambridge and the Low Carbon Built Environment Team, Welsh School of Architecture, Cardiff University – illustrate these trends. Both carried out whole building embodied carbon calculations. Neither followed a formal Soft Landings process, but they did carry out similar activities, such as liaising with residents on the systems that would be installed and their operation, and having at least two years of POE.

Both carried out energy performance modelling and set energy use and/or space-heating demand targets at the design stage (but not contractual). Their energy performance compared with the existing stock and industry targets is in Table 1.

No changes were made to this year’s forms – remember, the deadline to submit your project is September 5. Small changes are being considered for next year’s forms, including:

- Asking applicants to submit the building footprint: this would allow the projects’ PV output to be compared with emerging UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard (NZCBS) targets for onsite renewable generation, which are currently proposed to be in kWh.m-2 per year of building footprint

- Modifying the language for reporting on batteries: the form currently asks for annual energy ‘used by the battery’, which does not seem to be understood consistently and could incorporate energy that transits through the battery but is used in building operations, as well as energy lost in storage

- Automating some checks on energy breakdowns, especially those relating to how onsite energy generation is used.

If you have any questions or comments about the entry forms or would like to contribute project exemplars to inform industry net zero targets, contact Julie Godefroy, CIBSE head of net zero policy, at jgodefroy@cibse.org.

For a full list of 2024 Awards categories and to enter visit www.cibse.org/bpa

References:

- ‘Making data count’, CIBSE Journal, April 2021 bit.ly/CJMDC

- ‘Fuller disclosure’, CIBSE Journal, June 2022 bit.ly/CJBPAdata22