The Great Gallery, The Wallace Collection, London: the laylight provides much of the light in the gallery

The previous version of the SLL LG8, which covers the lighting of museums and art galleries, was published in 2015. However, there have been a number of dramatic changes in lighting technology in the past six years, so an update was required.

Many different professionals, with varying amounts of expertise and experience, are involved in the lighting of museums and galleries. The responsibility for lighting can end up with someone who is not an experienced lighting designer, so this guide aims to help people with all levels of expertise. Hopefully, though, it may make some non-specialists realise they need to employ a lighting designer.

LG8 is not just about museums and galleries, but covers a wide range of building types. It is also about historic interiors, which are displays in themselves. This new version aims to help the lighting designer, or person responsible for the lighting, to emphasise the story, themes or brand of a project, whatever its nature.

As in other sectors, it is the technology of how light is made and controlled that has changed drastically. The 2015 version of the guide still had, quite rightly, much information on tungsten halogen and metal halide fittings, and not as much about LED ones.

At the time, LED technology was in a rapid period of evolution, which made finalising the 2015 edition very difficult. However, the guide made clear that they were likely to be the principal source of light for museums and galleries in the future – which has, indeed, turned out to be the case.

As tungsten and metal halide sources are not specified any more, all references to those types of light source have been removed from the new guide, and replaced with more detail about LEDs and the technology that exists to support them. This includes information about drivers and dimming.

LEDs have even changed the economics of access for maintenance. As they last so long, some galleries now find it cheaper to hire abseilers to carry out the rarely needed maintenance, rather than have the infrastructure for big, heavy, high-level access platforms.

Another lighting technology revolution that has occurred recently is the development of the internet of things, so this – and various other innovative lighting control and communication systems – are also covered.

It is not the responsibility of the lighting designer to know what an artefact is made of and to decide what light level it can stand

While technology has evolved rapidly in recent years, humans and their eyes, and their feelings, have not. Light has not changed. Schemes for museums and galleries are among the most human-centred projects on which a lighting designer can work. So, this guide covers the subjective and human responses to light extensively, and how the lighting designer can influence these responses.

The publication starts with the foundations of lighting design, and explains what light can do and how it can be controlled. This is important, given that some readers will not be lighting specialists. Where museums and galleries are concerned, there are many particular challenges – such as reducing reflections and glare, and getting colours and relative intensities right – that can only be solved if the principles of light are understood.

The three great variables – brightness, colour and direction – are analysed and explained, and the guide helps describe how they control glare, affect the softness of shadows and the rendering of colour.

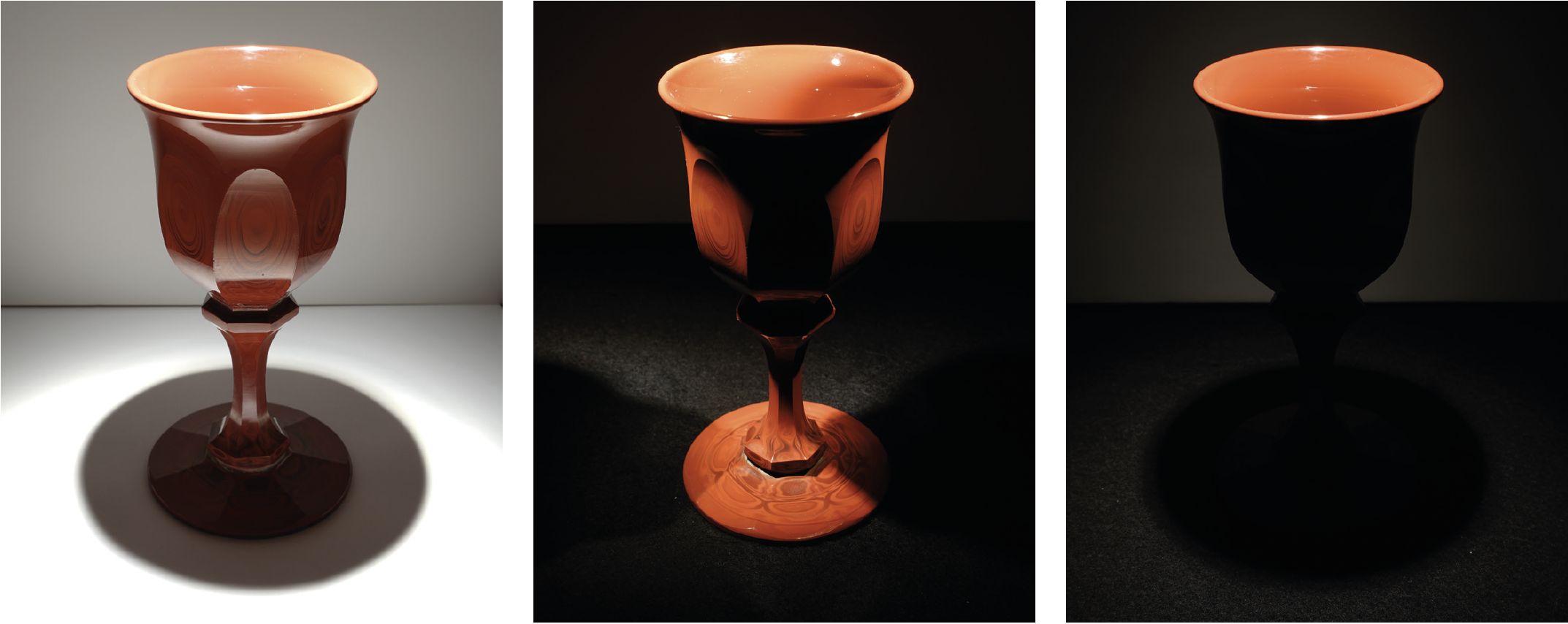

Using these and many other tools, the designer can make lighting emphasise the hierarchy of the story being told by artefacts, the supporting material and the spaces. The photographs below show a typical museum artefact lit from different angles with typical museum light fittings. They demonstrate the huge range of effects that can be created by just altering the brightness or direction of the light.

Museum lighting is rarely a blanket solution. There are often lots of details to solve and the best results are usually only found by experimentation. With this in mind, new sections have been added to the guide about the importance of aiming, adjusting, focusing and setting light levels once exhibits have been installed.

One of the major, perennial challenges of museum and gallery lighting is the damage that light can cause to objects. Light can fade colours and even cause some materials to break down. This is one of the great dilemmas of the museum world. A visitor only knows an object looks beautiful because they can see it. The visitor can only see the object if it is lit. But that light might be damaging the object and destroying its beauty. That is the challenge of lighting some artefacts: see, enjoy and, so, destroy, or don’t see and don’t enjoy – or somewhere in the middle, with some enjoyment and an acceptable amount of damage. The guide explains the amount of damage caused by different light levels.

An artefact with lighting from different angle from typical museum light fittings – a ‘huge range of effects can be created by just altering the brightness or direction of light’

The earlier version listed the amount and type of damage that light does to specific materials, so the designer could work out what level of light a delicate artefact could accept. This is one of the big changes to the updated guide.

It is not the responsibility of the lighting designer to know what an artefact is made of and to decide what light level it can stand. It is the responsibility of the artefact owner to say how much light they are prepared to use to satisfy their decision about the acceptable levels of enjoyment versus damage.

Technology has changed, but how light works, the damage it can do and the amazing effects it can create have remained constant, and are explained in detail. I suspect the reactions of human beings to lighting, involving eyes and hearts, will also remain constant, and these factors are the most important parts of the new version of LG8.

About the author

Mark Sutton Vane FSLL, is director of independent lighting consultancy Sutton Vane Associates and author of Lighting Guide 8 – Lighting for Museums and Art Galleries.

LG8 is available on the CIBSE Knowledge Portal at www.cibse.org/knowledge