External insulation was installed on the semi-detached Cambridge City Council homes

A retrofit project in Cambridge has demonstrated that social housing can meet the sustainability targets of the UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard (UK NZCBS), but the team behind the scheme also make clear that funding remains a critical barrier.

The sustainable overhaul of 48 homes in Ross Street and Coldham’s Grove, for Cambridge City Council, was submitted as a pilot project for the UK NZCBS, an emerging framework that includes performance-based targets covering operational energy and embodied carbon. The retrofit strategy included extensive fabric upgrades, low-temperature air source heat pumps (ASHPs), mechanical ventilation with heat recovery and onsite solar generation.

Although the design phase began before the Standard pilot was published, the process gave a clear understanding of where design decisions aligned well with the UK NZCBS, where they exceeded it, and where unavoidable constraints in existing housing made compliance more challenging.

A technical overview

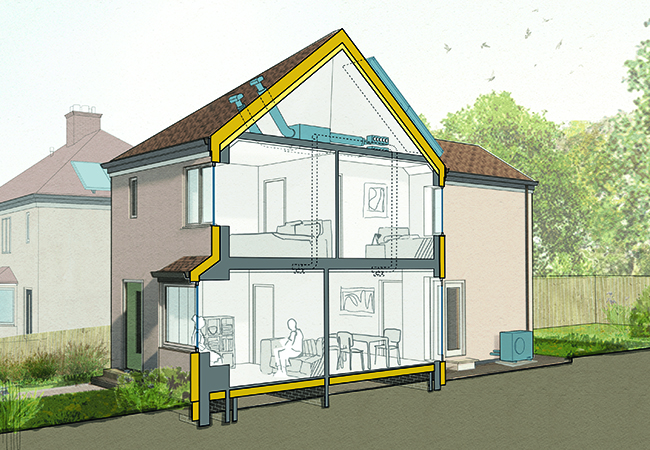

Combined with low carbon heating and onsite renewables, a fabric-first approach was fundamental to the success of the project. Reducing space-heating demand is the most reliable way to improve comfort, reduce energy bills and enable low carbon technologies to operate effectively.

Fabric improvement measures included external wall insulation, rafter-level roof insulation, suspended floor insulation to the front of homes, perimeter underground insulation, triple glazing, and airtightness measures. By significantly improving the building fabric, systems such as mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) and heat pumps were able to run efficiently and predictably. Without this level of insulation, there was a risk of creating homes that were expensive to heat, potentially leading to affordability issues, resident dissatisfaction and unintended consequences, such as condensation and mould.

Heating and hot water were provided by ASHPs designed to operate at a maximum flow temperature of 45°C with a delta T of 5K. Radiators were assessed and around 50% replaced to ensure adequate output at low temperatures.

To maintain air quality, MVHR was installed throughout, supplying fresh air to habitable rooms and extracting from kitchens and bathrooms. Additionally, gas cookers were replaced with electric alternatives, and low-flow taps and showers were added where required.

Each home was fitted with between 2.4kWp and 4.0kWp of PV capacity. No batteries were installed; instead, any residual electricity generated and not used by the ASHP is transferred to phase change material-based thermal stores or hot-water cylinders. There was no need for local grid upgrades, thanks to early engagement with the Distribution Network Operator, which confirmed this.

While fabric improvements made these technologies viable, the original renewable generation targets in the UK NZCBS remained challenging on constrained, existing roofs. Compliance was ultimately achieved through the Standard’s allowance for exemptions in existing buildings. Heat pumps play a role in achieving operational carbon reductions. Combined with fabric upgrades, onsite renewables and, where possible, battery storage, they offer a scalable and future-proof solution.

Routing pipework and MVHR ductwork was the greatest challenge, often requiring visually intrusive ceiling-level boxing and prolonged disruption for residents. Space and integration were also significant constraints. Finding suitable locations for external heat pumps and hot-water storage is often challenging in existing homes.

Meeting the Standard

The Cambridge project performed exceptionally well, successfully meeting nearly all the mandatory limits required for alignment with the UK NZCBS.

The project achieved a ‘Yes’ for being fossil fuel-free and comfortably stayed within carbon limits, with embodied carbon at 141.9kg CO2e.m-2 GIA (well below the 270 limit) and refrigerant GWP at a negligible 3kg CO2e.m-2 GIA against a limit of 677.

The embodied carbon of the MEP systems was calculated using OneClick LCA. The scheme was able to meet the embodied carbon metric with MEP equipment included (excluding PVs), with MEP accounting for approximately 14% of total embodied carbon for stages A1-A5.

Additionally, its operational energy of 40.53kWh.m-2 GIA per year was significantly better than the 75kWh.m-2 GIA per year limit, although these figures currently rely on modelled data rather than in-use metered data.

While the project technically failed the target for onsite renewable electricity generation, producing only 34kWh.m-2 building footprint/year against a target of 75kWh.m-2 building footprint/year, the assessment notes that the limit was effectively met through exemptions because of site-specific constraints.

Delivering a deep retrofit with residents in situ was complex. Plumbing modifications associated with external wall insulation and the installation of MVHR ductwork required access to multiple rooms. Coordinating these works while residents remained in their homes required detailed planning, flexibility and ongoing engagement.

The experience reinforced that deep retrofit in occupied homes is possible, but it requires realistic programming, significant flexibility, and a strong, trust-based relationship between the contractor, client team and residents.

It is still early days, but, overall, residents have responded positively. There has been an initial learning curve, particularly around heating controls and ventilation systems, so providing ongoing support, clear guidance and reassurance has been essential. Residents received handover booklets, with links to videos, supported by in-person demonstrations from the MEP installer team. An Energy Action Day, including manufacturer demonstrations, took place near the end of the contract.

Uptake of social housing retrofit to the UK NZCBS requirements is likely to be limited in the short to medium term because of cost and disruption. While the Cambridge project demonstrates that the Standard is achievable, funding for Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund measures falls short of the deep retrofit expenditure required per home.

Embodied carbon also remains challenging. Although bio-based materials could reduce impacts, risk aversion in the post-Grenfell regulatory environment often limits their use. Solar generation is particularly difficult in retrofit, making the Standard’s renewable exemptions for existing buildings necessary and pragmatic.

Overall, the project shows that deep retrofit aligned with the UK NZCBS is achievable, but only where funding, client ambition, delivery models and the right team are fully aligned.

About the author

Loreana Padron is head of sustainability and associate director at ECD Architects