In the UK, fire safety legislation and associated guidance are currently undergoing an unprecedented process of scrutiny and change. As part of this, many of the common assumptions and ‘norms’ relating to the design of buildings are being reviewed. Opportunities to improve and develop safer, more inclusive, and more sustainable approaches are being identified.1,2,3

With increasing numbers of mid/high-rise buildings, and growing numbers of people that may have difficulty getting out of a building, the traditional solutions for vertical evacuation need to be reconsidered. In residential apartment buildings especially, people should be able to safely evacuate regardless of their physical, cognitive or sensory capabilities to navigate stairs safely.

An obvious strand of tackling this vertical evacuation challenge would be to increase the use of lifts in emergencies. However, the public have generally been taught that: ‘in the event of fire do not use the lift’.

This article aims to highlight some primary considerations about the use of lifts for the evacuation of people who cannot use stairs. It identifies a number of challenges and opportunities to be addressed as part of enabling their incorporation in fire strategies.

What are we aiming for?

When a building is designed/constructed, or significantly refurbished or extended, it must be demonstrated that the building can satisfy the relevant functional requirements of the Building Regulations 2010 (as amended). The design must also enable the responsible person for the building (typically a building manager or owner) to comply with fire safety management requirements imposed under legislation such as the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005 (FSO).

Further explanation on the intent of the Building Regulations is provided in Approved Document B (ADB), the statutory guidance to the legislation, with ADB Volume 14 for dwellings and ADB Volume 25 for buildings other than dwellings.

The traditional solutions for vertical evacuation need to be reconsidered

ADB Vol 1 and 2 clarify that building designs and building management plans should not rely on the fire service or other emergency services to evacuate residents who need assistance. ADB Vol 1 and 2 also state that the fire safety measures in a building should take account of the needs of everyone who may access the building. (See the version of this article at www.cibsejournal.com to see a summary of applicable legislation and guidance in England and Wales. Similar regulatory frameworks apply in Scotland and Northern Ireland, and elsewhere.)

The status quo

In buildings other than residential apartments (for example, offices, places of assembly, and hotels), persons for whom using stairs is not possible or safe are typically expected to wait at a protected refuge position. The responsible person(s) is expected to address responding to refuges and assisting those using them as part of their emergency plans and personal emergency evacuation plans (PEEPs).

[The latest Home Office consultation on Personal Emergency Evacuation Plans can be found here].

Manual carry-down equipment/procedures are typically implemented to assist with the onward evacuation of wheelchair users from these refuge areas.

In apartment buildings, ‘refuges’ are not typically provided, nor are they included in current UK guidance. The only means of vertical escape is usually via stairs, as standard ‘passenger’ lifts would typically be grounded and therefore discounted for emergency escape.

Those who cannot use a stair therefore have no means of self-evacuating or communicating with management (if there is any on site). (See full article for information on guidance for non dwellings).

ADB Vol 1 (for dwellings and flats) mentions neither refuges nor evacuation lifts. The alternative UK standard for fire safety of apartments, BS 9991:20156 notes that: ‘Providing an accessible means of escape should be an integral part of fire safety management…’ which ‘…should take into account the full range of people who might use the premises, paying particular attention to the needs of disabled people.’

BS 9991: 2015 notes that responsibility for achieving these objectives rests with building management but provides only high-level guidance. It encourages consideration of inclusive features such as evacuation lifts when designing escape routes. Some contradictory commentary is provided however, suggesting that occupiers also have responsibilities (see full article for more).

BS 9991:2015 Clause 8.4 does reference the use for evacuation lifts where considered necessary for people needing assistance, and points to the guidance in BS 9999:2017. The BS 9999:2017 approach requires the lift to be driven by a trained member of staff, so is not viable where there is no suitable onsite management presence, which includes many residential buildings.

Therefore, stair refuges plus carry-down/carry-up procedures remain as the prescribed alternative. However, such approaches can bring their own safety risks. They can also be unrealistic or even impossible for building operators to implement, particularly in taller buildings.

It is evident that for flats, there is a lack of prescribed solutions for safe and inclusive evacuation of persons who cannot evacuate on their own in the event of fire.

However, these shortcomings do not obviate the need for designers to meet the legislative requirements, stated intention and functional objectives set out in statutory guidance. They also do not relieve building operators of their duties under the FSO.

Current lift design guidance benchmarks

Two main lift types provided in buildings that are designed to be used in the event of a fire are evacuation lifts and firefighters’ lifts (note: the latter could also be used to assist with the evacuation in certain situations).

Older standard lifts for fire service use (for example, lifts referred to as firemen’s lifts) may also be present in existing buildings. The level of functionality and protection afforded to these older lifts vary.

It is also possible that a lift installation not explicitly designed as an evacuation/firefighters’ lift could be used for egress purposes as part of a case-specific fire risk assessment/fire strategy.

Guidance relating to lifts to be used in the event of fire is spread through documents originating from both the fire and lift industries. Table 2 in the online version of this article provides a list of current UK guidance documents.

Evacuation via lifts – options, challenges, opportunities

There are opportunities in progress to improve current fire safety guidance relating to evacuation lifts. ADB is undergoing ongoing technical review by the MHCLG and a revision to BS 9991:2015 is also under way (see online article for examples).

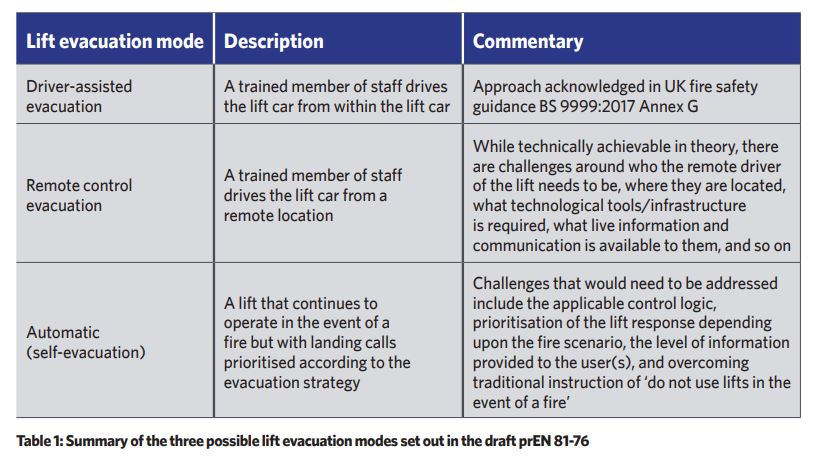

The recent draft prEN 81-76 captures some emerging thinking on how evacuation lifts could operate, and outlines specification options for three different types of evacuation lift operation – see Table 1. However, as a draft, prEN 81-76 is not a standard and should not be used for design.

The Lift and Escalator Industry Association (LEIA) has published guidance7 clarifying the status of the draft prEN 81-76, including its reference within the draft guidance to the new London Plan on the Greater London Authority (GLA) website.8

There is a need for a multidisciplinary approach, to develop practical interventions to increase the use of lifts for evacuation

Other challenges and opportunities that appear to need addressing to implement more progressive thinking in relation to evacuation lift provision:

- Increased dialogue between the fire safety and lift industries: It is crucial that those with design and specification responsibilities relating to fire safety and lift installations have a practical understanding of each other’s needs, and potential opportunities/limitations of lift technology.

- Increased prescriptive guidance relating to evacuation lift provision: For most building types, there is a lack of prescriptive guidance relating to evacuation lifts (for example, when to provide them, how many, how to protect the lifts). As a result, there is a temptation to focus on achieving minimum standards compliance, and the clear benefits of providing evacuation lifts may not be fully considered. There is a need to shift the outlook on evacuation lift provision from ‘nice to have’ to ‘should we have?’

- Increased awareness of the implications of not providing an evacuation lift: Lifts are often seen as a significant tool in the improvement of accessibility in buildings. Similarly, evacuation lifts could be promoted as integral to ensuring safe egress for all. Without an evacuation lift, evacuation of people from refuge areas to a place of ultimate safety will rely upon a building management team response such as manual carry-down. This can be difficult, and may present challenges for the Responsible Person discharging their duties under the FSO and as part of the future ‘safety cases’ to be required by the forthcoming Building Safety Bill [2].

- Proactive consideration of retrofitting for existing buildings: A culture change is needed, away from the common ‘make things no worse’ approach to identifying what safety enhancements can be made. In particular, in a refurbishment, the additional works required to provide functionality for use in fire can be cost-effective and should be encouraged. Providing protection to the lift spaces and lobbies, and providing secondary power supplies, can present challenges, but can be overcome.

- User familiarity, and the psychology relating to using lifts during a fire: Staff must have familiarity with lifts to be used in the event of fire. Occupants also need to know which lifts can be used, how they may operate, and what level of staff assistance will be provided, if any. Human psychology, behaviours and perceptions relating to the use of lifts must also be considered. In some buildings, the provision of relevant information, training, and pre-event planning could be suitable. For occupants who do not need to use a lift for evacuation, additional information may be necessary to encourage them to continue to use the stairs, in order to avoid overloading the lift(s).

- Learning from existing lift evacuation strategies: A number of existing buildings (in the UK and globally) use lifts as part of their evacuation procedures. Valuable lessons in terms of building management could be learned from these.

The way forward

This article discusses the importance of lift evacuation to help overcome the current shortcomings in inclusive fire safety in existing UK building stock, and which still proliferate in current design practices. The article identifies a number of challenges that will need to be addressed.

There is a need for a multidisciplinary approach to the subject, to develop practical interventions to increase and improve the use of lifts for evacuation. Opportunities are also emerging to embed the increased use of lifts for evacuation within the UK regulatory framework and guidance/design standards.

The authors wish to stimulate debate among those involved in the fields of building design, fire safety, accessibility, and lifts, to help bring about the step-change required in regulations, standards and practices relating to inclusive design for fire safety.

About the authors

Eoin O’Loughlin is a senior fire engineer and Harry Wiles is a fire engineer at Arup, and Matthew Ryan is an associate director at The Fire Surgery

Acknowledgements

This article has benefited from review and input from Lynsey Seal and Gareth Steele of London Fire Brigade, and Nick Mellor of the LEIA. There have also been contributions from a number of staff at Arup, namely Judith Schulz and Michael Kinsey from fire engineering, Julian Olley and Thanos Samaras from vertical transport, and Mei-Yee Man Oram from inclusive environments.

References:

- Building a Safer Future – Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety: final report,” MHCLG, 2018.

- Draft Building Safety Bill, MHCLG, 2020.

- Fire Safety Act 2021, MHCLG, 2021.

- Approved Document B (fire safety) volume 1: Dwellings, 2019 edition incorporating 2020 amendments, MHCLG, 2020.

- MHCLG, Approved Document B (fire safety) volume 2: Buildings other than dwellings, 2019 edition incorporating 2020 amendments, MHCLG, 2020.

- BSI, Fire safety in the design, management and use of residential buildings – Code of practice, BSi, 2015.

- New London Plan – evacuation lifts guidance, Lift and Escalator Industry Association. (Accessed 03 06 2021).

- Draft Guidance Sheet for the New London Plan Policy D5(B5) for Evacuation Lifts, GLA (Accessed 03 06 2021).