It isn’t that long ago that control systems for architectural lighting were regarded as a bolt-on, rather than an integral part of a lighting design. From a budgetary point of view, they could be easily lopped off as an unnecessary extravagance.

They were regarded as somehow arcane and complicated. Anecdotal evidence suggested that, where they were installed, they might be left on a default setting or manually overridden, because no one really understood how to operate them.

Lighting Guide 14: Control of electric lighting, first published in 2016, was an indication that things had changed. ‘A decade ago, it was quite common for lighting controls to be seen as an optional extra to schemes, and they would often be “value engineered” out of a project,’ says Sophie Parry, author of the first LG14 and the new update.

‘The aim of LG14 was to demystify, as far as possible, the subject of lighting controls, and allow informed and objective decision-making for the application of controls to lighting projects.

‘In the eight years since LG14 was conceived, the industry has evolved to the extent that automatic lighting controls are now an essential and integral part of the majority of lighting designs. The key reason is the versatility of LED light and its easier controllability.’

As a result, there has been a sharpening of purpose and a notable rise in the use of lighting controls in applications such as energy reduction, wellness, and exterior lighting.

Why lighting control is integral to good design

- Energy reduction: the cost of energy has risen significantly, and controls can deliver an annual financial saving on energy costs of at least 20-30%, in addition to the savings made with LED lighting. Daylight linking, dimmability, and presence and absence control are all key facilities in reducing energy use.

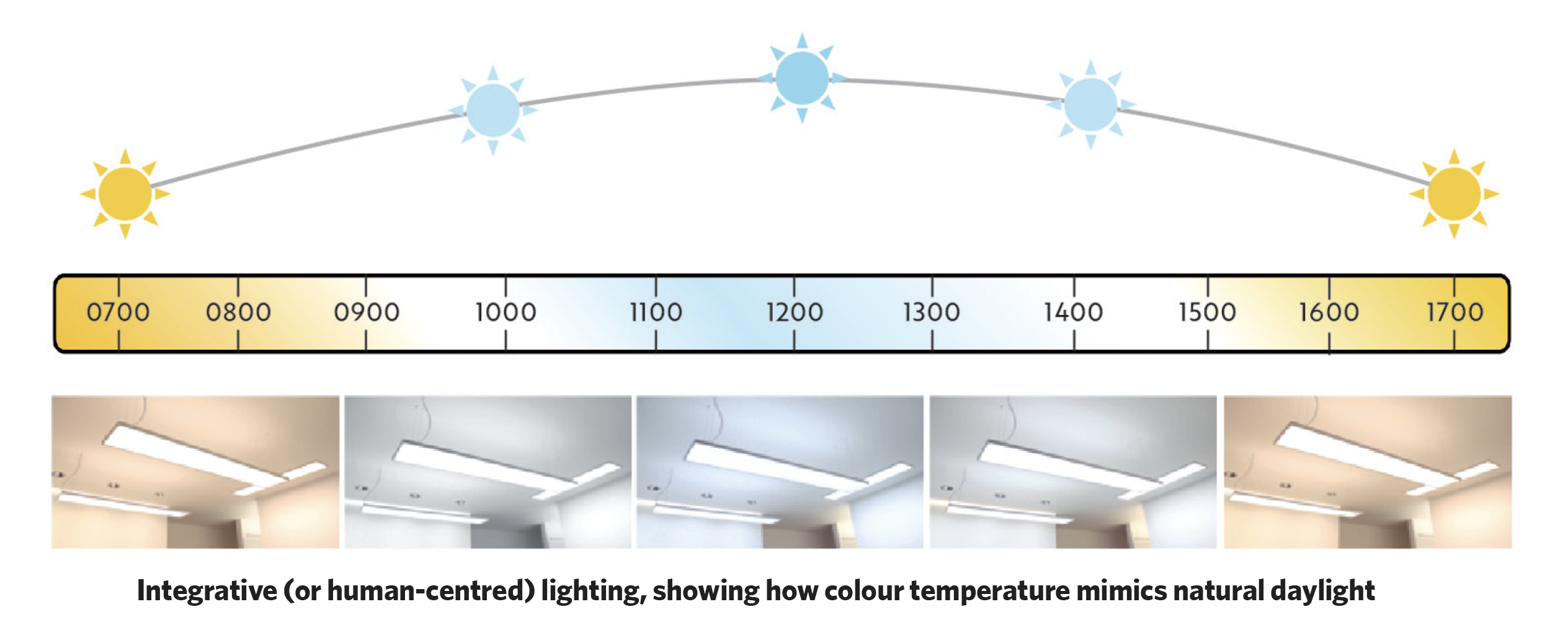

- Wellness: the growing recognition of the importance of wellness in the workplace has meant a newer role for control systems. Both daylight and electric light play their part in this area – they need to work in harmony to deliver good-quality illumination that considers photopic and melanopic light.

- Exterior lighting: there has been a significant rise in the use of external lighting that goes beyond just providing functional night-time illumination. Many external lighting schemes now use coloured light, and will often have the ability to create different lighting scenes to suit particular events and occasions. The flip side is that night-time light pollution has increased. However, in addition to good luminaire and lighting design, lighting controls can reduce light pollution and save operational energy and reduce operational carbon.

What’s new in LG14

The first chapter is an overview of advances in lighting control technology and applications since the first edition was launched in 2016, while the following chapter looks at the significant updates in terminology and acronyms used.

‘I have noticed that specifications often ask for certain aspects of lighting control performance on projects where the specification author is not entirely clear what the terminology means,’ says Parry. ‘There is, therefore, information on less-than-obvious terminology and its application.’

Chapter three focuses on how to design and manage clients’ expectations. ‘The best approach is to design the lighting and specify the luminaires to be used, then determine, with the client, how the lighting should be controlled to suit requirements,’ says Parry. ‘These will include meeting legislative or performance-related energy saving stipulations, in addition to the client’s needs.’

Once performance criteria are established, the correct lighting controls can be selected. ‘It’s also a good idea, at this stage, to revisit the luminaire schedule, to ensure that the luminaires contain – or can be supplied with – compatible control gear, to ensure correct operation with the lighting control system,’ says Parry.

The fourth chapter focuses on the human factor and the impact lighting has on the people using the spaces. This includes examining typical spaces where different modes of lighting control are known to be most effective. Considerations should include whether absence or presence detection is necessary, for instance – or if a risk assessment shows that automatic lighting controls that suddenly switch the lights off unexpectedly could be a health and safety risk.

Chapter five covers the use of lighting controls for creating visual interest and visual comfort. Correct luminaire control gear and compatible lighting controls will be required for the operation of integrative (human-centric) lighting schemes.

Energy reduction is one of the key applications for lighting controls, and is the focus of chapter six, which particularly looks at legislative requirements.

LG14 uses Approved Document L of the Building Regulations, Vol 2, for England as the basis of discussion. Approved Document L also includes the lighting energy numeric indicator (Leni) calculation method in its simplest form. This is reproduced with additional commentary in the second edition of LG14.

Leni is derived from BS EN 19193-1 Energy performance of buildings – Energy requirements for lighting and is considered the most accurate method of predicting lighting energy usage. It also allows for the benefits of lighting controls to be calculated. The output of the calculation is expressed in kWh·m-2 per annum.

‘This means that the projected cost of lighting energy and the carbon footprint can be calculated easily,’ says Parry. ‘If factoring in, or factoring out, the energy-saving benefits of lighting controls, the lighting design starts to get interesting.’

This exercise can make two points, according to the guide:

- The annual energy savings as a return on making the investment in automatic lighting controls, as opposed to not using automatic lighting controls

- That the inclusion of automatic lighting controls might make the difference between compliance or non-compliance with Approved Document L.

‘That said, lighting designers often shy away from using Leni, because it can seem daunting and time-consuming,’ Parry adds. ‘However, as the industry moves towards a net zero carbon future, designers will have to embrace new design methodologies for preserving the required lighting quality and using less energy.’

The next section discusses data sharing and the role played by lighting control systems in smart buildings.

Information on room occupancy status provided by networked lighting control systems was already possible when LG14 was first published. The most common example at the time was to share room occupancy data in real time with the building management system to optimise the performance of HVAC systems.

There has been a marked increase in the use of controls to automatically test and generate fault and test reports for emergency lighting.

‘The use of the lighting control network with auxiliary sensors to collect additional useful data – such as lighting energy and maintenance, temperature, humidity, and air quality – makes it possible to create a more pleasant environment for the end user,’ says Parry. ‘It also enables more informed decision-making relating to building comfort, wellness, FM, and energy costs.’

However, she points out that the innovative technology also brings new engineering and design challenges, including cybersecurity considerations, which are explored in this section.

Chapter eight covers commissioning and handover, which, says Parry, ‘should be the most obvious subject, but sadly, in practice, it is not the case. Often, the more simple lighting controls installations are not fully commissioned and tested, which means they are not likely to deliver the design intent.’

LG14 recommends that commissioning should include a handover process, usually to FMs. It should involve an explanation of what can be done to effect maintenance or system changes, and be provided in layman’s terms. ‘Typical examples might include how to use a scene-setting switch in the conference room,’ says Parry.

The chapter also makes reference to CIBSE Commissioning Code L: Lighting, which was revised in 2018. ‘This provides the means of developing a commissioning method statement for a lighting installation project where the luminaires, controls, emergency lighting, and auxiliary data interfaces with other services form the basis of a common lighting design,’ says Parry.

The guide concludes with case studies of lighting control installations in places of worship, education and offices.

- Lighting Guide 14 (LG14): Control of electric lighting (2023) is available at bit.ly/CEL23CIBSE

About the author

Sophie Parry FSLL is head of the Trilux UK Akademie. and chair of SLL’s technical and publications committee. The article is based on one in Light Lines July/August 2023

Case study contributors:

David Holmes MCIBSE HonFSLL; Simon Robinson FSLL, technical director at WSP