The internet has had a long-standing problem – how do you trust the person or website you are doing business with?

The levels of internet fraud and theft are well reported and, by some estimates, running to billions of pounds per year. It is too easy to pretend to be someone else – so you never really know who you are dealing with.

Fortunately, most people are able to spot the obvious frauds. It is rare that a real prince is moving his funds from somewhere exotic and needs your help. But there are far more sophisticated frauds, which get through with alarming regularity.

How can this be solved? A system – called blockchain – has been devised that does not allow you to pretend to be someone else.

It was devised by Satoshi Nakamoto (not their real name, ironically) to overcome this problem, offering what is known as a ‘trustless network’ – you don’t need to have trust in the person you do business with because the network will do that for you.

The exchange of value using blockchain technology is carried out with ‘crypto-currency’. Most people are aware of Bitcoin, a form of crypto-currency, though few really understand what it is and how it works.

Distributed ledger

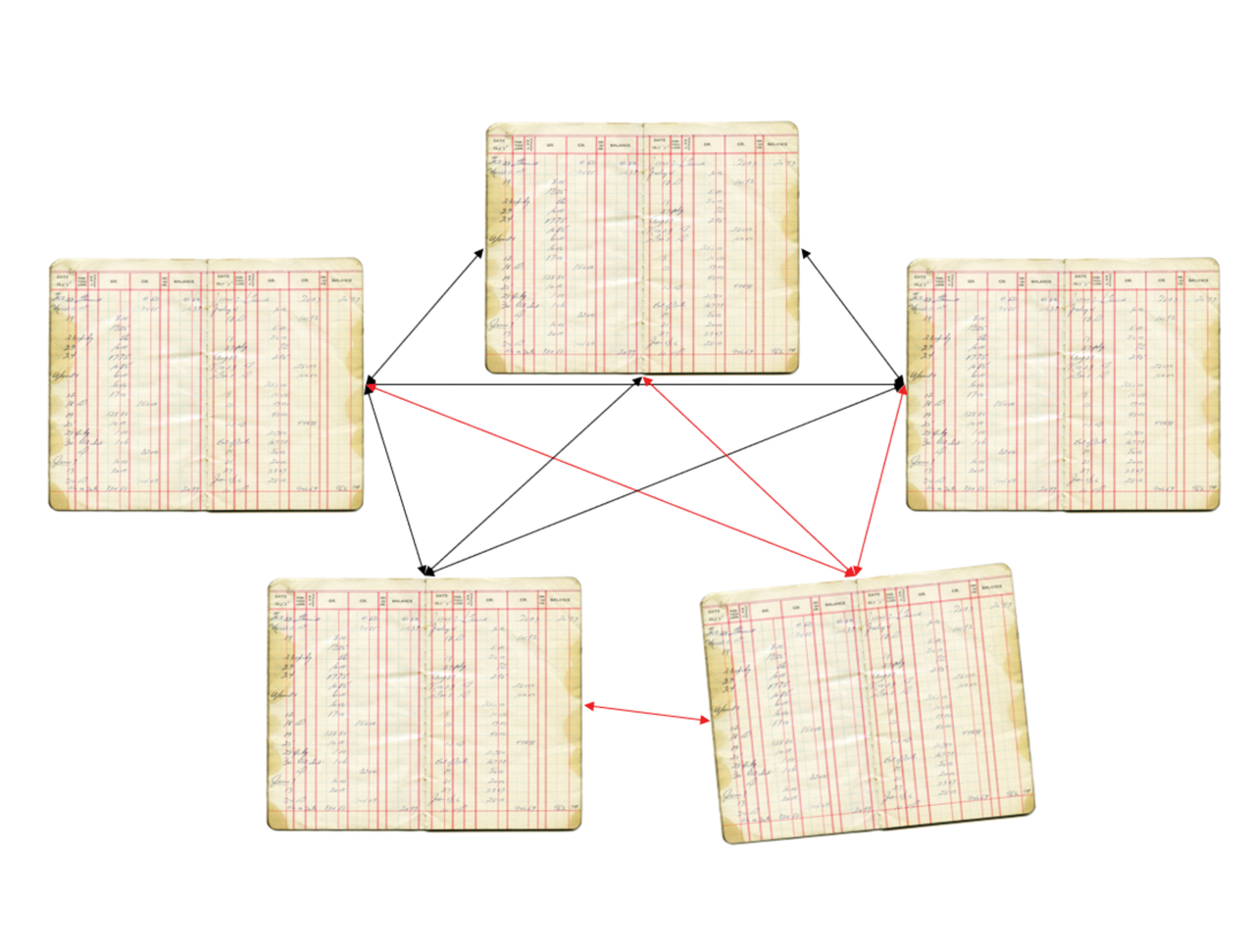

How does the blockchain work? The concept is remarkably simple. Consider a double entry book-keeping ledger, the income and outgoings have to match for the books to balance. Now, if everyone had a copy of that ledger and, if any one of them were different, the mismatching data would be rejected, so the books couldn’t be cooked?

That is the heart of blockchain – all its members have a synchronised copy of the ‘ledger’. The synchronisation happens over the internet and the code checks everything matches.

The ledger has a series of blocks – the entries we would see in a traditional version – but these can be discrete quantities of data, not just financial incomings and outgoings.

They are connected by an encryption engine that uses the data within the block to create a ‘key’. This key will only match the block immediately above and below, so its contents, once written, cannot be changed, or the chain of blocks will become corrupted and the system will reject the alteration.

The block

Each block has a payload of information, which can be about anything – computer code that could contain written files, spreadsheets or parts of a construction model.

The block is written to the blockchain when proof of work or value has been established, which may be by applying processing power or by demonstrating that value is being exchanged.

The purpose of this demonstration of work is to make it difficult to write data to the blockchain if your interest is in gaining value from it for nothing, for example a fraudulent transaction.

Relationship to fiat currency

Fiat currency is declared by a government to be legal tender and is not based on the value of the material used to create it. For example, five-pound notes are a token of value because they are not made of material that costs £5.

Crypto-currency is also an exchange of value, just using a different method – the blockchain. There are parallels that would imply we can exchange fiat with crypto and vice-versa. We can – and there are exchange markets for crypto-currency that translate the value to fiat currency.

The relative value of crypto to fiat currency is changing rapidly. The value of one Bitcoin is 48 times higher than it was two years ago. On 13 December, it was trading at £12,471.8, compared to £260.10 on the same day in 2015 (the original value of one Bitcoin was $1). It should be noted, however, that exchange rates are prone to sudden fluctuations.

It is entirely feasible to exchange fiat for a crypto-currency transaction and back again.

Figure 1: Block not synchronising with the blockchain

The aggregators

Some stand-out recent start-up companies have been those that aggregate services and their users, charging a fee to put the user in touch with the best or nearest provider.

A good example is Uber, which connects private hire drivers with passengers needing a ride. Another is Airbnb, sourcing accommodation for people wanting short-term lets. These firms are successful because they are big names that can be referred back to in case of dispute.

Blockchain removes the need for a trusted intermediary with its immutable history, making the aggregators superfluous. So, the first victims of blockchain may actually be some of the newest and most successful tech start-ups.

The distributed nature of the blockchain allows providers of, say, private hire vehicles, to be found directly using a mobile phone, with all the history of that driver available for the passenger to see. In addition, the driver will have a private blockchain ‘key’ that will prove beyond doubt that they are who they say they are. There would be no need for an aggregation service taking money from you, the passenger, and a driver to put you in touch and provide the trust link. This should make the journey cheaper.

As Vitalik Buterin, of Ethereum Blockchain, says: ‘Whereas most technologies tend to automate workers on the periphery doing mental tasks, blockchains automate away the centre. Instead of putting the taxi driver out of a job, blockchain puts Uber out of a job and lets the taxi driver work with the customer directly.’

In 2014, Buterin founded Ethereum, a blockchain with the ability to create apps built in, so programs could be run, and contracts execute themselves.

The relevance to construction is that Internet of Things (IoT) devices – gadgets that talk directly to the internet – can also be members of the blockchain and part of the supply chain.

Each proven piece of effort will be paid automatically – so no payment chasing and no retentions, with all transactions held immutably in the blockchain

Let’s go briefly through a small worked example: I want to build a house and I’m going to use blockchain to bring my design and delivery teams together. I can create a crypto-currency on my blockchain and give keys to each participant as they join. Each proven piece of effort will then be automatically paid to them – so no invoicing, no payment chasing and no retentions, and with all the project transactions held immutably in the blockchain.

As my designer uploads the design, he or she gets paid for their effort. As I approve the design they get paid to carry it forward to the next stage. If I want to order a palette of bricks, I invite the supplier onto my blockchain, order my bricks and – when the delivery driver arrives on-site – a barcode is scanned by an IoT scanner, proving that these are the bricks and they are onsite, immediately releasing payment.

As the bricks are used to construct the walls of my house, laser scanners and/or cameras can check the progress and assess the quality of the job, so my brickie is paid before he gets to the pub!

At the end of the project, I have a complete history of who made which decision and when it was made. In effect, I have the perfect information model to operate my new home, a true asset information model.

This is just a simple sketch of how blockchain could disrupt the construction sector. I’m sure people are thinking up far better uses right now, and some will be working out the flaws in the system.

And there will be flaws – this is a new approach not only to technology, but transacting financially and contractual relationships, but it is very exciting.

- Carl Collins is a digital engineering consultant at CIBSE