What is clear from COP26 is that we all need to deliver significant emissions reductions this decade. As designers, this means understanding better the emissions resulting from our designs and, potentially, challenging some of our preconceived ideas of what delivers low carbon or zero carbon buildings.

Having looked at what this means in new homes – recognising that re-use of existing structures is also critical – my initial analysis of what produces the lowest emissions in the ‘short term’, over the next 20 years (upfront emissions, plus 20 years of operational emissions), gave me some surprises.

I felt it would be useful to share these initial findings, which I’m sure many of you will instinctively think are incorrect – but I invite you to run the numbers yourselves and really challenge yourself on what will save carbon emissions in the next 20 years.

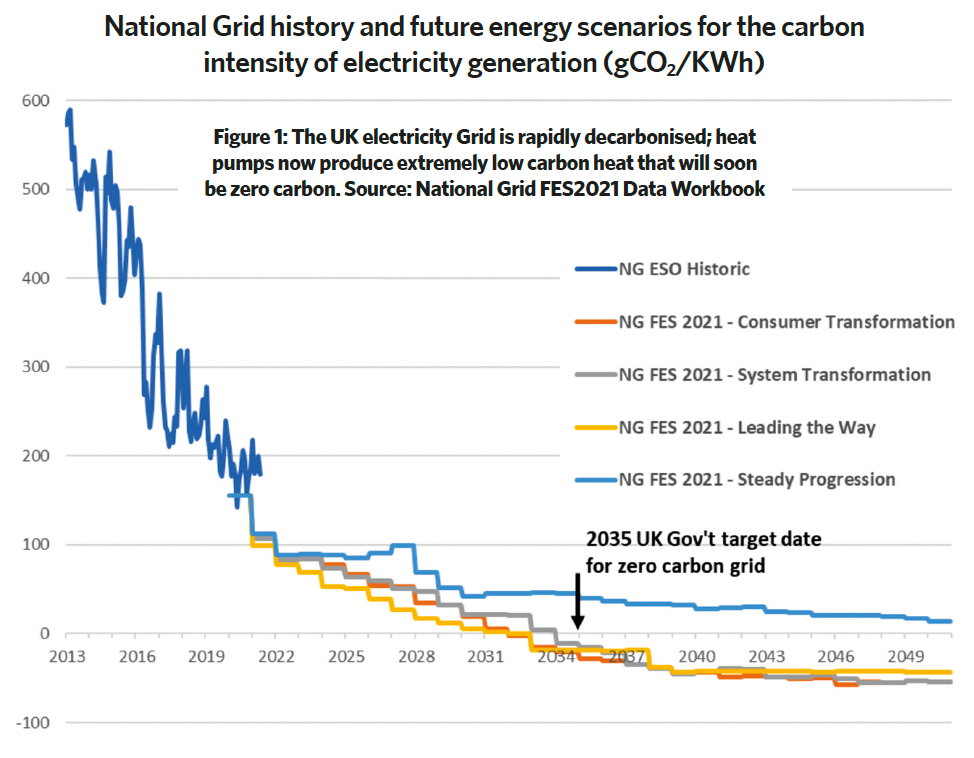

Use heat pumps

Hopefully, everyone is aware that the electricity Grid has significantly decarbonised and that a grid-connected heat pump delivers very low – and, increasingly, close to zero – carbon heat (see Figure 1). We can’t continue burning natural gas, and ‘green’ or ‘blue’ hydrogen won’t be here in any scale in the next decade (or two). Heat pumps, however, have a huge knock-on impact on how much extra upfront carbon we should spend on other measures to save heat, as saving heat energy won’t save much carbon in the 20 years of using a heat pump.

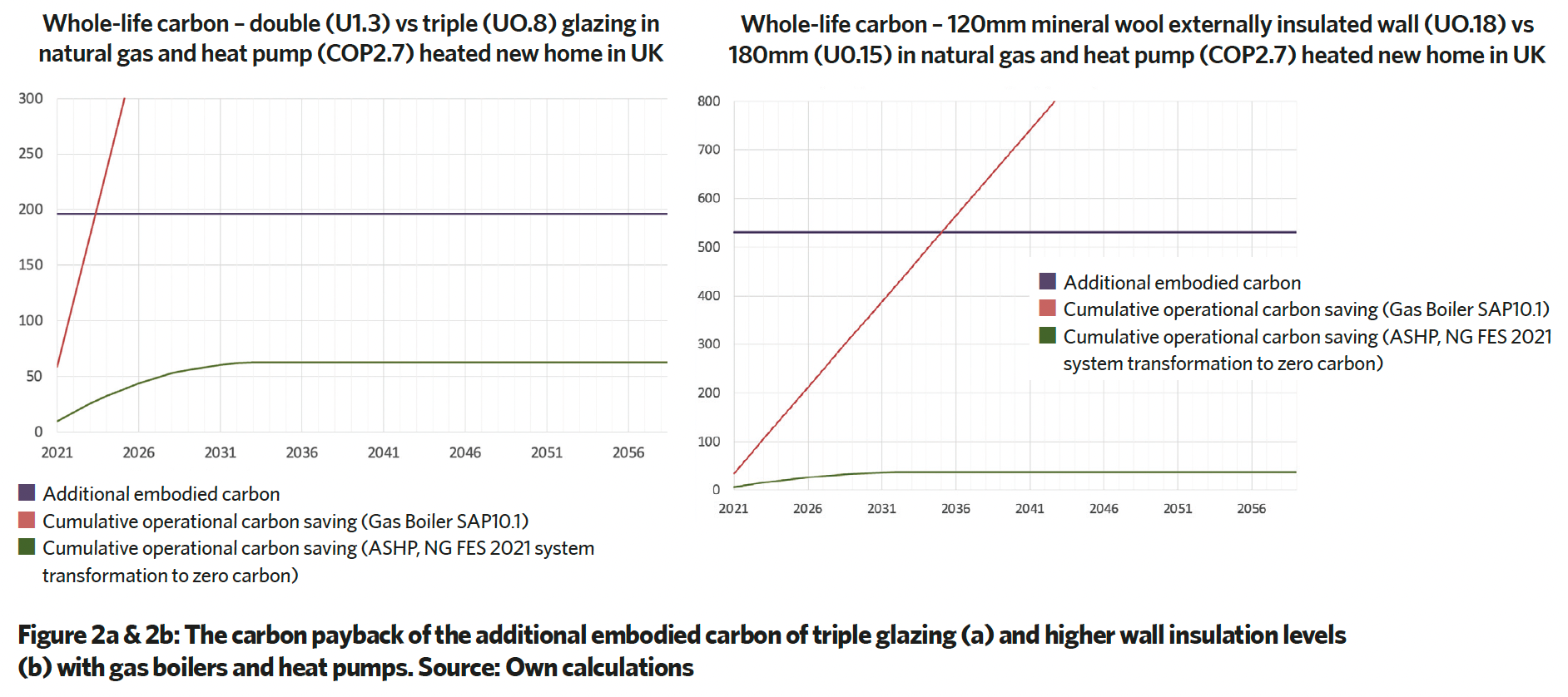

Don’t go too far on fabric

For example, a U0.8W·m-2·K-1 triple-glazed window has higher upfront emissions than a U1.2W·m-2·K-1 double-glazed window. With a gas boiler, this upfront carbon ‘pays back’ in two years but in an air source heat pump- (ASHP-) heated new home, it never pays back (Figure 2a). There is also a limit on how far to go with wall insulation. Adding 60mm of mineral wool to an externally insulated wall improves the U-value from 0.18 to 0.15, but this upfront carbon never pays back with ASHP. However, the upfront carbon pays back in 14 years with a gas boiler (see Figure 2b).

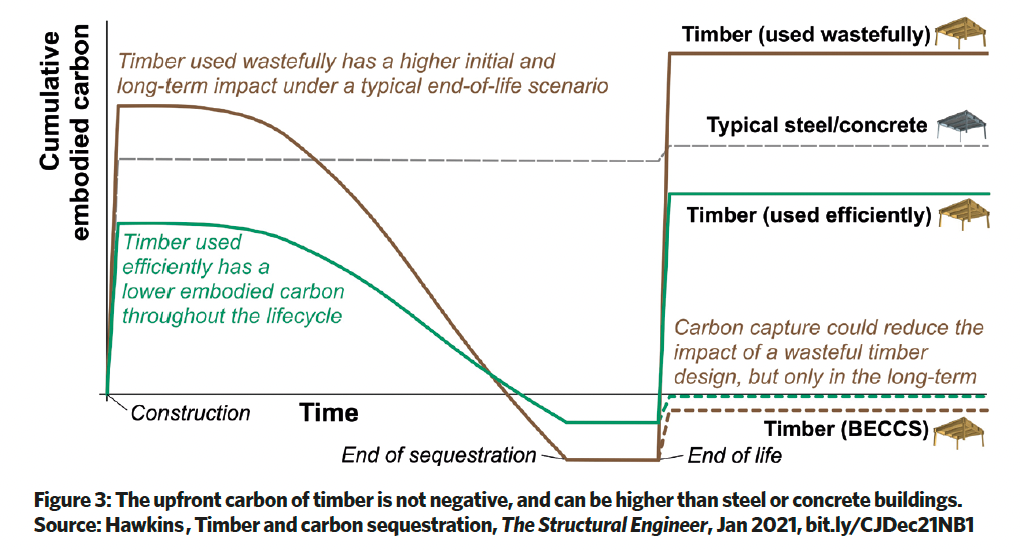

Bio-based materials may not help

The chart in Figure 3, from a recent IStructE paper, really helped me understand why sequestered carbon from bio-based materials is not included in upfront carbon. Cutting down a tree adds to emissions today, and it is the tree that replaces the one cut down that gradually sequesters carbon. Trees typically have a 50-year harvesting cycle, so other bio-based materials with a faster, or annual, harvesting cycle (hemp, straw) may be more helpful in the short term

Don’t connect to gas CHP district heating…

unless you know the heat you get is already below 0.04kgCO2e/kWh. Gas combined heat and power-led heat networks are now worse than natural gas boiler-heated ones. Not many heat networks will use heat pumps this decade – and even if they do, the network losses may mean a local heat pump is lower carbon, especially if there is a lot of new pipework to lay (upfront carbon) to connect you up.

Solar needs to be ‘in-roof’ to help

Unless solar PV is replacing high-embodied carbon finishes, such as concrete or clay tiles, they are likely to increase emissions because of their relatively high upfront carbon and because the energy they are now offsetting is much lower carbon.

Batteries don’t help much either…

specifically, on carbon emissions. They have a high upfront carbon footprint and waste electricity (around 10% per charge, with a typical round-trip efficiency of 90%). However, they are enabling more renewables onto the Grid, ,can make heat pumps much cheaper to run, and can slightly reduce emissions by moving your electricity use to the night, when electricity is cheaper on a smart or Economy 7 tariff and, generally, 10-30% lower carbon. Spending £3-5,000 on a domestic battery can lower bills by as much as £500 per year, significantly more than if spending about the same on upgrading windows from double to triple-glazed, which results in a £10-30 per year saving (depending on tariff/heat source).

Keep it simple

Simple building forms, MEP systems and controls usually mean less upfront carbon, and they are less likely to go wrong – although a means of measuring performance to know if things have gone wrong is probably a form of upfront carbon that is well worth including!

Stay up to date

The data on upfront carbon will evolve as the Grid evolves, so we need to stay alert to changes. For example, if a zero carbon glassworks opens, triple glazing makes sense again from a carbon-footprint perspective.

The short-term emissions numbers with heat pump heating really changed my thoughts, and is now influencing our upcoming designs.