Despite numerous reports calling for it, there is still no clear national retrofit strategy from government. The 10-Point Plan is, for the building sector, merely a small list of mostly existing policies, not a comprehensive strategy. If Boris Johnson is, as he recently said, ‘more and more obsessed’ with climate change, this would be a good place to prove it and start work.

Government is not short of advice: the Climate Change Committee (CCC) makes a number of recommendations in its 6th Carbon Budget, and the Construction Leadership Council has published a national retrofit strategy for consultation.

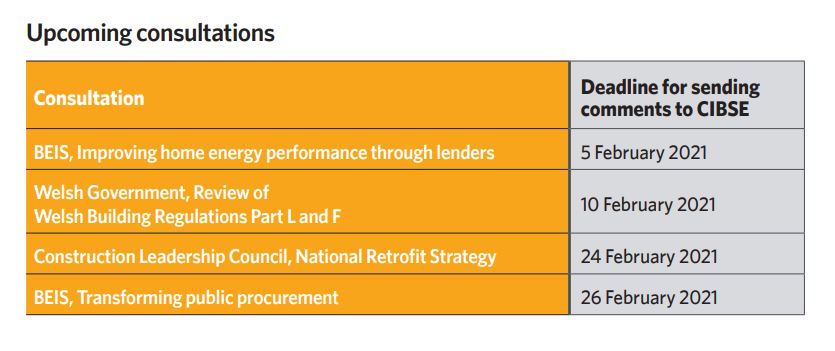

In the meantime, government departments are consulting on a number of individual policies to improve the existing building stock, including one on private rented sector (PRS) homes.

Tackling privately rented homes

The Improving the energy performance of privately rented homes consultation proposes amending the PRS regulations to improve energy performance and, in doing so, improve residents’ comfort and health, and develop retrofit supply chains. This is significant: PRS represents 4.8 million – or 20% – of households in England. Properties are typically in a worse condition, and fuel poverty much more prevalent, than in owner-occupied and socially rented homes.

The government’s preferred proposals are to require a minimum EPC rating of C (currently E), phased from 2025 to 2028. This would be subject to a £10,000 cap, so landlords would be exempt from meeting the rating if they could show work to achieve it would cost more than this cap.

CIBSE supports the ambition to start the huge task of improving the existing housing stock

An alternative government proposal would require a dual rating of EPC C and an Environmental Impact Rating (EIR) – a CO2 rating – of C. This would be subject to a £15,000 landlord cap. Its aim would be to drive the low carbon heat transition, as EPC ratings – despite being called energy efficiency ratings – are, in fact, cost-related. At current prices for electricity, compared with fossil fuels, they can actually favour continued fossil-fuelled solutions.

CIBSE very much supports the ambition to start the huge task of improving the existing housing stock. Currently, EPCs are not the right tool. First, because in-use energy data from large-scale housing samples shows some correlation between improved EPC ratings and actual energy use, but nowhere near the scale required; energy savings are too small and energy use levels of the best-rated properties are far higher than needed. Second, because of their inability to drive heat decarbonisation through the use of a cost rating.

Ultimately, it would be more effective to reform EPCs to be based on energy use. This could be coupled with a space-heating indicator to drive fabric improvements – for example, space-heating demand as in Passivhaus, or heat transfer coefficient (HTC) if the BEIS Smart Meter-Enabled Thermal Efficiency Ratings (Smeter) trials conclude that HTC measurements are possible in a reliable, cheap and non-intrusive way.

Heat decarbonisation should be addressed separately – for example, by capping maximum EPC ratings if fossil fuels are used, and through regulations to phase out fossil-fuel installations. This has also been noted by the CCC, which says that improving the existing stock means ‘reforming EPCs to make them fit for purpose’.

The consultation also includes a number of valuable proposals to improve compliance and enforcement and drive high-quality works. It would be useful to link PRS requirements to the use of PAS 2030/5 to improve quality, evaluate outcomes to reduce the performance gap and avoid unintended consequences, such as poor air quality, overheating or fabric degradation.

Much-awaited: Part L and F

MHCLG has just published its response to the Part L & F 2020 and Future Homes Standard consultation for new dwellings, and the consultation on the remaining elements (overheating, and Part L and F for existing dwellings and new and existing non-domestic buildings). See page 7, CIBSE Journal, January 2021.

- All current and past consultations and CIBSE responses are at: bit.ly/CJFeb20JG

- Send comments on any of these consultations to Julie Godefroy JGodefroy@cibse.org

- Dr Julie Godefroy is technical manager at CIBSE