The latest Tesla electric vehicles run off 85 kWh battery packs – enough energy to drive a car 265 miles or to run an average house for a week. But, what are the likely implications of these simple facts for the way we think about energy and, in particular, the way we manage energy in buildings?

Electric vehicles (EVs) are already here and, while projections about take-up vary, they will probably number in the millions within a relatively short time. From an energy perspective, large numbers of electric vehicles mean vastly more flexibility and fluidity in the system. That’s not all; it also means a completely new infrastructure and additional demand for electricity, all of which needs to be managed. But it is the flexibility and fluidity that we’ll all probably notice most.

Increased demand for electricity

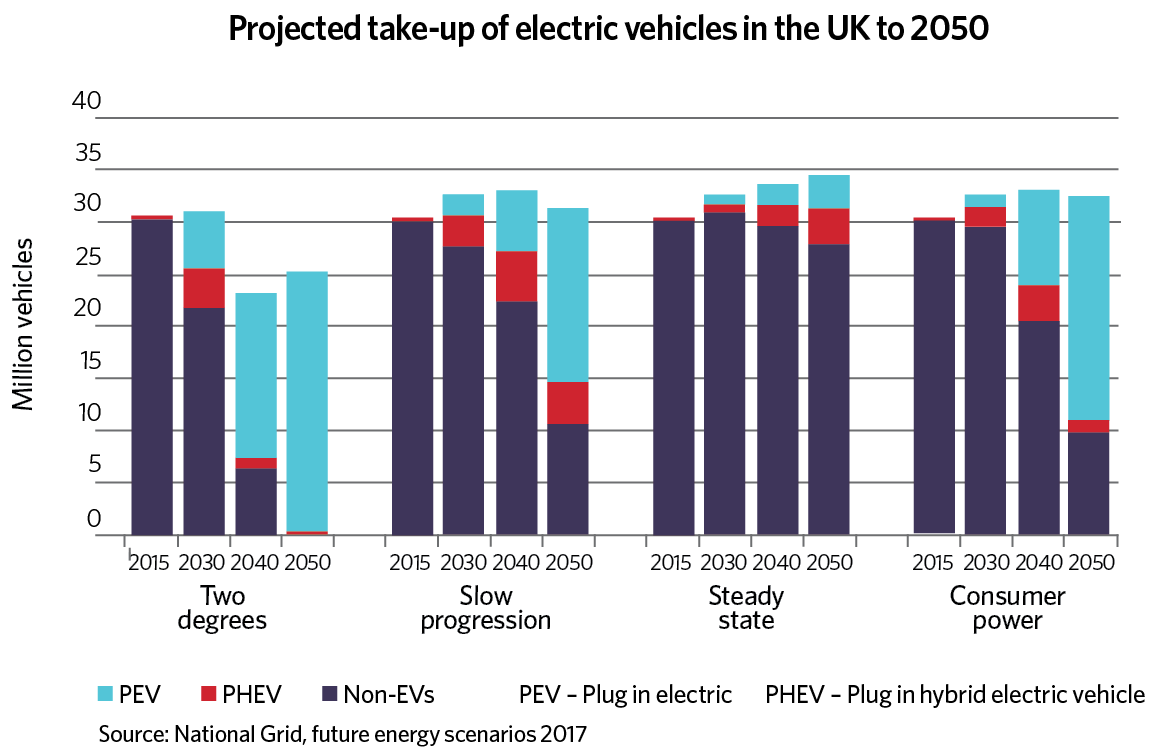

National Grid estimates that the UK will need between 6GW and 18GW of additional generation capacity by 2050 to cope with the increased numbers of EVs1. Interestingly, the 6GW estimate relates to it most radical ‘two degrees’ scenario, while the 18GW reflects its more conservative ‘consumer power’ projection. The difference is an assumption, in the more radical scenario, that we will also adopt much more varied business and charging models, such as less vehicle ownership and more optimised charging and use of vehicles, often offered to us on a shared and autonomous model with centralised managed charging.

In context, 6GW is two to three large, traditional or nuclear power stations, or about 10% of current national peak power demand – so not as challenging, perhaps, as some observers might have first suggested, especially if we have until 2050 to build these stations and can already see the need. But something tells me it’s unlikely to be so simple.

Every million new EVs on our roads represents up to 50GWh of storage

Novel infrastructure

The kind of radical reduction in peak power requirement from 18GW to 6GW suggested by National Grid requires sensible, planned energy-infrastructure investment in the right locations – for example, ‘super-hubs’, where autonomous EVs can return for charging, or travellers can switch from fossil- or hydrogen-fuelled, long-distance transport systems to regional and local EVs. It also needs effective charge-management algorithms and business models to emerge relatively quickly.

The omens for such outcomes aren’t great. At the recent Ecobuild conference in London, a government spokesman blithely announced they are planning simply to prohibit charging at certain times of day to reduce the risk of excess demand. This seems a draconian and short-sighted measure, which will simply inhibit innovation and alienate customers. Much more effective approaches – for example, using time-varying tariffs as incentives – would be more effective in encouraging electric vehicle take-up and use of all this additional storage capacity in a way that benefits the national system.

On the other hand, there are innovations being developed and trialled nationally. In Milton Keynes, induction charging is used at bus stops to keep electric buses charged during the day, to reduce demand when they return to base at night2. At Ecobuild, Western Power Distribution (WPD) presented on its Electric Nation project. This has more than 700 EV drivers trialling smart-charging systems, allowing WPD to control when vehicles charge at night (subject to a customer opt-in) to optimise use of the distribution network3.

Flexibility and fluidity

It’s the flexibility and fluidity that EVs offer the national system that excites me the most, though. Even with an average battery pack of 50kWh per vehicle, every million new cars on our roads represents up to 50GWh of additional storage capacity in our energy system – equivalent to virtually the whole generation capacity of the country running for an hour.

This capacity will move around, but not necessarily in an unpredictable way or, indeed, for most of the time. According to the RAC, the average UK car spends 96.5% of its time parked4 – outside a person’s home or place of work. Either way, the vehicle is following the main source of energy demand and demand volatility: the driver.

Battery charging and management is becoming increasingly slick and sophisticated – as the Milton Keynes example illustrates – and includes vehicle to grid options, as well as the traditional grid to vehicle.5 So we suddenly have a world in which the average home or office has a whole new energy-management tool at its disposal – especially businesses that pay quite complex electricity bills, reflecting usage patterns and total demand, which might have hundreds of parked cars outside every day.

Current thinking about the opportunities this creates tend to focus on the value to the national system: ‘What if the system had a (free) 50GWh storage asset as part of its portfolio? Do we really need that extra power station for peak demand, or could we design incentives to smooth out the national demand profile and use our new storage asset efficiently?’ But there’s probably quite a lot of virtue in thinking through the potential for individual homeowners, communities and businesses. What about taking my house (or business) off grid for a couple of days while the electricity price is particularly high? Or selling use of my storage asset to an aggregator to offer balancing services to the grid for a suitable fee? Or installing a solar system to do my own charging and minimise grid costs?

People relate to cars and mobility in a different way to how they relate to buildings and energy, so look out for a whole new world of customer engagement in the energy system – coming our way very soon.

References:

- National Grid, Future Energy Scenarios, July 2017, ngrid.com/2HVSgcH

- Maq Alibhai, Wirelessly charged electric buses in Milton Keynes, www.eurotransportmagazine.com 12:2 (2014), bit.ly/2G11jZb

- www.electricnation.org.uk

- RAC Foundation, Spaced out: perspectives on parking policy, 17 July 2012, bit.ly/2GSmU7H (Most studies put the figure at about 95%).

- Jonathan Susser, Not just a car: The possibilities of vehicle to grid technologies, www.advancedenergy.org, 4 October 2017, bit.ly/2G4AbZl

Matthew Rhodes is an independent consultant. He chairs the Energy Capital initiative in the West Midlands. https://www.energycapital.org.uk/.