Keeping a digital record – or ‘twin’ – of the design, construction and occupation phases of a building is one of the key recommendations in Dame Judith Hackitt’s post-Grenfell report into Building Fire Safety Regulations.

A chapter of her report is dedicated to ‘the golden thread of building information’. It echoes the challenges faced by many industry professionals when it comes to the effective handover of information after construction and the maintenance of records during the building’s life.

Among Dame Judith’s other recommendations are having open and non-proprietary formats for digital records, and giving responsibility for transferring and updating information to a duty holder for the life-cycle of a building.

For a new-build design, it should be relatively straightforward to ensure the digital history of a design passes usefully into the hands of the operator – but how do you even start to create a digital twin for an existing building with ‘as built’ information that might be 30 years old and poorly maintained?

That was a question I asked myself when I began to focus solely on improving existing buildings. For a start, what is a ‘digital twin’? While it can be said to be a computerised version of something that exists in the physical world, there is no definition of how computerised something needs to be to reach the increasingly desirable ‘digital twin’ status. Is a building information model (BIM) a digital twin? What about a tagged PDF plan layout? Depending on what you read or who you speak to, you could conclude they are or they are not.

In 2013, I started working for a large real-estate services company, having just witnessed the process of creating the government’s BIM level 2 exemplar project, HMP Cookham Wood. I was ready to tell everyone about the exciting potential of BIM, but two questions I kept facing in my new role were: ‘What is BIM and how will investment in it pay back?’

Unable to give a satisfactory reply at the time, I decided to seek answers by trying to create a digital twin – and I started with the question ‘what’s in our building and how do we capture it’. This sparked my interest in reality-capture techniques, and the routes to, retrospectively, creating a digital twin are listed below, in the order that I discovered them.

LiDAR and trace

In 2013, light detection and ranging (LiDAR) was not new, but it was incredibly expensive. I was able to get a ‘proof of concept’ piece of scanning done in a relatively new office space that was changing hands.

After removing a 6m by 6m section of ceiling tiles, I soon realised the first challenge of retrospectively capturing existing buildings: most of the purposeless content of the ceiling ended up on the floor.

Capturing everything (visible and hidden) can be disruptive to the building users, so be clear what everything is, for example only what is useful going forward. The LiDAR scan was successful and, after a complicated processing phase, I was ready to recreate what was a data-lite BIM.

The static LiDAR scanner image and the point cloud that sit behind it took 1.5 days to capture and process

At this point, the second challenge of retrospective BIM became apparent. The process of translating point clouds into models – even with today’s software solutions – is laborious and time-consuming.

The output I had was a simplified digital twin of the space. This, however, generated the third challenge – how we present data from a digital twin in a way that engages all stakeholders. If it’s not clear and easy to access and maintain, it will lose synchronisation with reality and not be trusted.

Tagged panoramic photography

A former colleague of mine suggested the digital twin may be equally as useful if it is a picture or floor plan with some data tags attached to it. Most existing buildings have layout drawings, even if they are simplified fire plans proudly framed next to main entrances.

At the time, the first generation of cost-effective, one-click panoramic cameras had become commercially viable for pilot projects. Using low-cost images attached to floor plans, I was able to create the skeleton of a digital twin.

The fourth challenge had arrived: how could I attach meaningful information from disparate databases into photos? For now, a useful record of the building had been created, which linked floor plans to panoramic pictures. From a maintenance perspective, this later proved to be a level of BIM that was useful to those who operate buildings. It’s not unusual for reactive maintenance teams to arrive at a space to fix something at height, only to find that it is 6m off the floor rather than 3m, resulting in abortive trips and inefficiencies.

Equally, tagging key safety features – such as emergency lighting and smoke detectors – makes auditing otherwise unnoticed changes much easier. For example, the panoramic photo shows there should be a smoke detector where there isn’t one. Perhaps these are the simple efficiencies we, as an industry, should be trying to address first with our entry-level digital twin.

3D Cameras

The growth in use of 3D capture cameras has been incredible. One such camera, made by Matterport, uses a combination of photos and infrared depth measurements to generate a walk-through environment similar to Google Street View. The capture process is akin to LiDAR.

Once captured, processing to create the final model is all done in the cloud. In addition to the Google Street View-esque environment, Matterport delivers a low-density point cloud that can be used to reconstruct environments with most mainstream modelling tools.

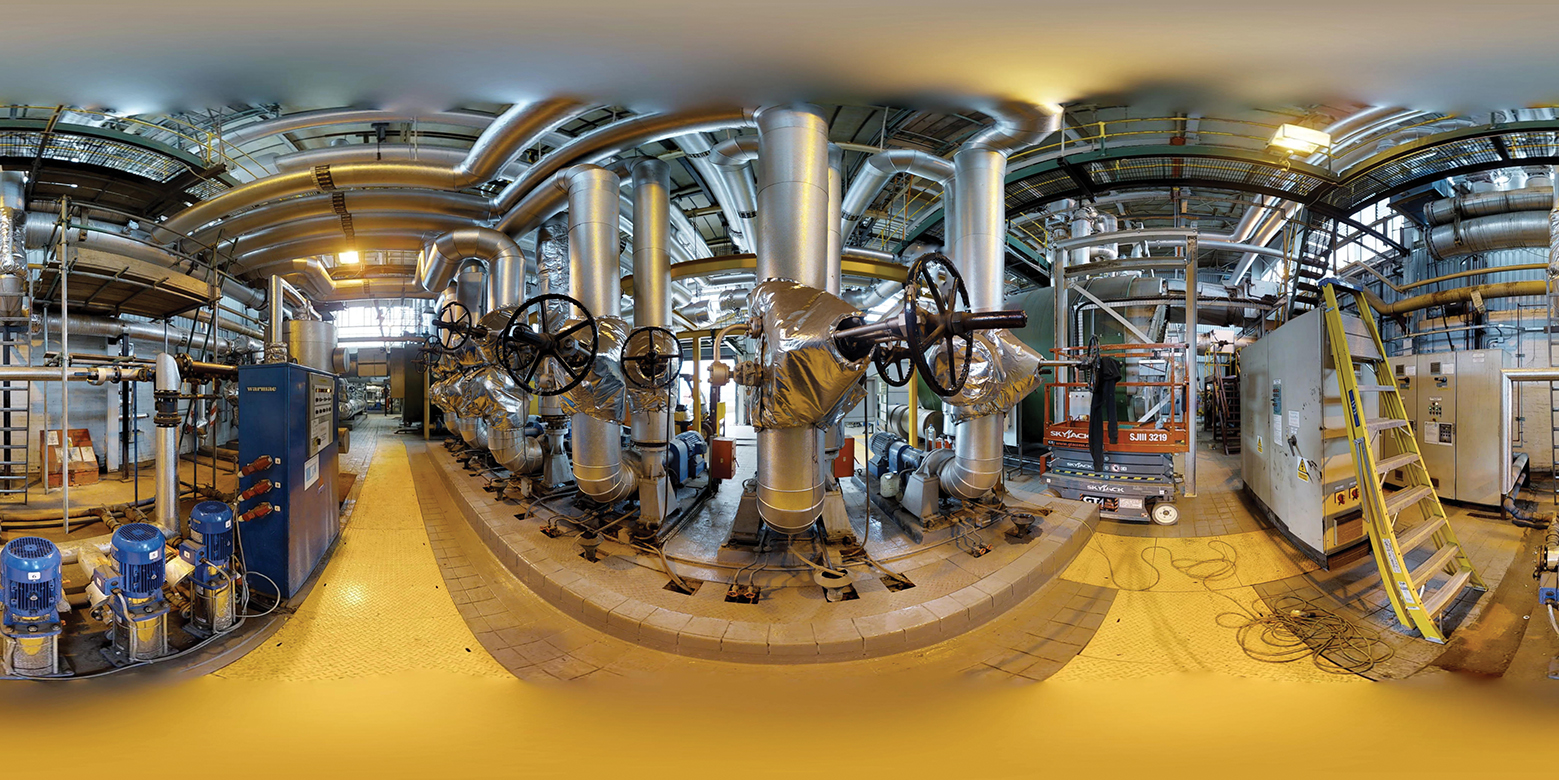

3D camera image of Matterport boiler can link to useful data

More importantly from a digital-twin perspective, the software allows you to deliver web-based content back into the model environment – for example, sensor data. It also clearly highlights the fifth challenge: data security, which often pulls in the opposite direction to accessibility and ease of sharing.

With the improvement of handheld, simultaneous localisation and mapping (Slam) technology, more routes to creating a digital twin retrospectively will become available. For fire safety, it could:

- Show clear escape routes for all occupants of the building, which dynamically respond to the building activities

- Highlight important features of fire safety and allow people to visually, or even automatically, check/compare what is actually present with what should be present – for example, fire compartments and smoke detectors

- Provide a visual insight to the building for firefighters before they arrive at the scene

- Deliver a visual index to statutory information and the golden thread of information.

Equally, with minimal reimagination into other sectors, it may:

- Offer the chance for a parent to look around a school if they couldn’t make the open day

- Give an autistic person foresight of the potentially stressful environment they could face when going to an unfamiliar place

- Allow wheelchair users to have an improved experience of a hard-to-access listed building.

Reality capture has a part to play in creating the digital twin, which could offer a means to access the golden thread of information mentioned in the Hackitt report.

If we are to create digital twins retrospectively, I would recommend:

- Limiting disruption during the capture process and only capturing what is useful going forward

- Gaining an understanding of the limitation of each capture methodology and the time it takes versus the value it brings to the end user

- Planning how the digital twin will be presented (remember your audience) and how it will be kept current, as this will impact on trust, uptake and future maintenance

- Understanding where the data for the digital twin will come from, and making sure it can receive this data without creating copies (multiple sources of the truth)

- Considering the implications of sharing data, and its sensitivity or potential to create security loopholes in other connected systems.

Using low-cost panoramic camera images attached to floor plans, the skeleton of a digital twin could be created

About the author

Derek Lawrence is associate director, Buildings Midlands, at Arup