The number of people living with dementia in the UK is rising sharply. In 2024, approximately 850,000 people were affected, and this figure is projected to double by 2040. The financial burden is also increasing, estimated at £42bn in 2024 and projected to reach £90bn by 2040.

In response, researchers are exploring how the built environment can support the wellbeing of people living with dementia (PLWD). A recent study investigated a real-world care home to assess potential links between indoor air quality and incidents of agitation and aggression.

Dementia is a group of neuropsychiatric syndromes that cause progressive impairments in memory, thinking and behaviour. These symptoms can escalate to behaviours such as restlessness, agitation and aggression – defined as verbal or physical actions intended to harm or repel others. Up to 90% of people with dementia exhibit such behaviours, which are distressing for both patients and caregivers, and are associated with increased medication use, hospitalisation and mortality.

Pharmacological interventions such as psychotropic medications and sedation carry significant risks, including cognitive decline and increased mortality. Non-drug-based interventions are therefore critical to managing these behaviours safely and effectively.

While architectural design has been shown to influence wellbeing in care settings, there remains limited understanding of how specific environmental and sensory conditions – such as air quality and temperature – affect behavioural symptoms. As a result, built environment professionals may lack the tools to design environments that reduce stress and aggression in dementia care.

The physical environment plays a vital role in quality of life for residents. Research has linked poor homeostasis, agitation and aggression in PLWD to indoor air quality and thermal conditions. For example, maintaining temperatures between 22°C and 24°C was correlated with reduced incidents of aggression in a monitored care setting.

Indicators of air quality, particularly carbon dioxide (CO₂), have long been used as proxies for inadequate ventilation and crowding. Elevated CO₂ levels are also associated with increased risk of airborne infections.

A collaborative study between the Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Trust (CNTW) and Newcastle University’s School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape examined the relationship between indoor air quality and behavioural incidents. The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Environmental conditions were monitored in an NHS inpatient facility specialising in the management of severe behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. The research team monitored CO₂ levels, temperature and humidity, while the psychiatry team at CNTW anonymised incident reports of agitation and aggression.

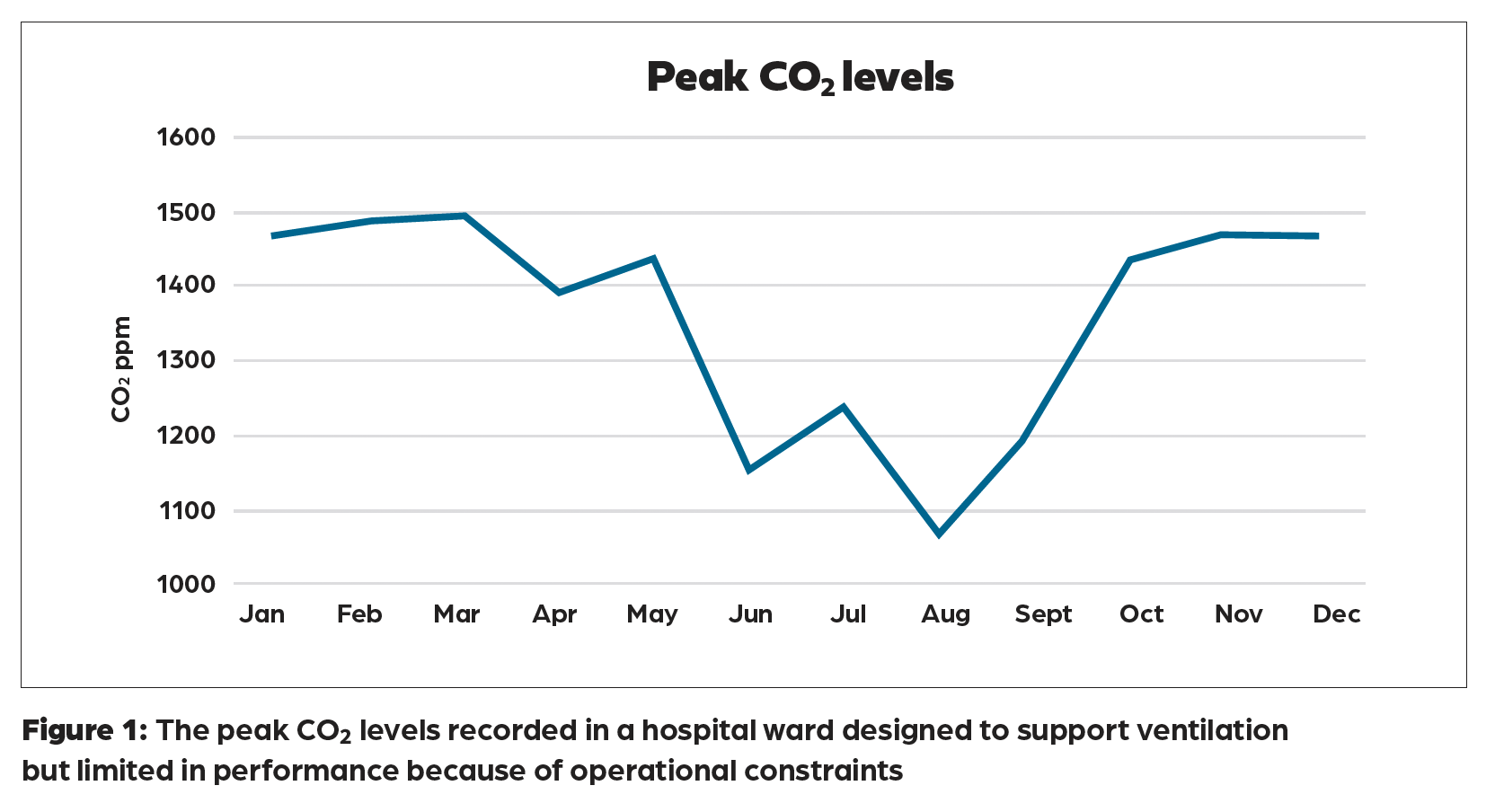

Although the ward was equipped with high-level windows intended to support cross-ventilation, the responsibility for opening them fell to staff already engaged in extensive one-to-one care, making regular ventilation difficult to maintain. The air conditioning systems included controls for temperature and humidity, but lacked CO₂, particulate matter and volatile organic compound monitoring.

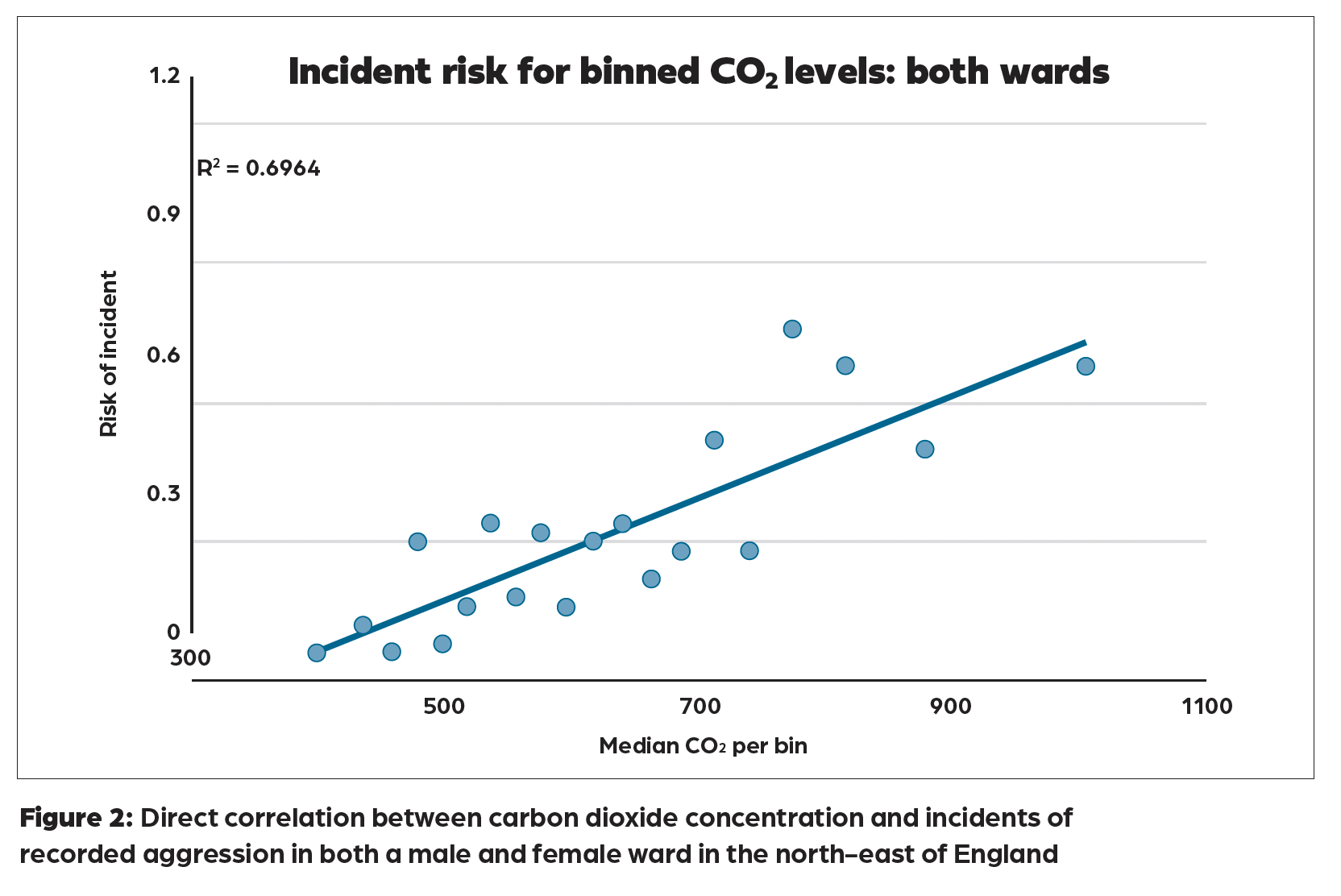

The study found that levels of aggression increased as CO₂ concentrations rose, even when concentrations remained below the commonly cited threshold of 1,000 parts per million (ppm). Notably, behavioural effects were observed at concentrations around 800ppm, suggesting that even modest increases in CO₂ may influence behavioural outcomes (Figure 2).

To extend the findings, building performance simulations were conducted in collaboration with Dr Mohamed Mahgoub, at the United Arab Emirates (UAE) University. These examined the impacts of increasing ventilation rates under current and projected climate conditions.The measured air change rate in the ward was approximately 1 air change per hour (ACH). Modelling explored a range of scenarios from 2 to 6 ACH and found that reducing CO₂ levels below 800ppm would require increasing ventilation to 4 ACH. This would lead to a 23% increase in annual energy use under current climate conditions.

Despite additional energy use, better ventilation could significantly reduce incidents of aggression and medical interventions, easing the burden on staff and potentially improving care outcomes for PLWD.

Supporting wellbeing for people living with dementia through environmental design

A growing body of research is exploring how internal environments can be optimised to support the wellbeing of people living with dementia. A recent systematic review of studies published between 2007 and 2024 highlights several other key environmental factors:

Daylight exposure has been shown to help regulate circadian rhythms, and may reduce sleep disturbances and mood-related symptoms.

Noise levels – whether too high or too low – can contribute to agitation and distress, underscoring the need for acoustic balance.

Thermal comfort is also critical, with increased behavioural symptoms observed when conditions are perceived as too hot or too cold.

These findings suggest that both overstimulation and understimulation of environmental factors can contribute to behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Carefully managing light, temperature and acoustic conditions can improve comfort and reduce the incidence of challenging behaviours.

References:

1 Au-Yeung WM et al ‘Examining the relationships between indoor environmental quality parameters pertaining to light, noise, temperature and humidity, and the behavioural and psychological symptoms of people living with dementia: scoping review’ Interact J Med Res 2024;13 doi: 10.2196/56452 bit.ly/CJPLWDsc24

- The paper ‘Do indoor environmental conditions affect behaviours of people living with dementia?’ (Hamza et al) was presented at the CIBSE IBPSA-England Technical Symposium. Papers will be available later this year at www.cibse.org/symposium

About the author

Neveen Hamza is professor of architecture and building performance at Newcastle University, and chairs IBPSA-England.

The paper’s co-authors are: Dr Mohamed Mahgoub, associate professor, Department of Architecture, UAE University; and Dr Keith Reid PhD, consultant forensic psychiatrist, Dr David Anderson, consultant psychiatrist, and Dr Leigh Townsend, specialist psychiatrist, all at CNTW.