It is perhaps no surprise that Mike Davies is a big fan of building services. He was, after all, part of the team – alongside Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano – that designed the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the building that put its services out front and taught the world that ductwork is nothing to be afraid of.

In the 43 years since the Pompidou project turned architecture inside out, Davies has become one of the most distinguished – and distinctive – figures in British building design. A partner in the Richard Rogers Partnership (now Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners) since 1977, he has led the teams responsible for many of the practice’s most high-tech buildings, including the Millennium Dome and Heathrow Terminal 5.

On all of these projects, services have played an instrumental role in the design approach. Here, Davies reveals the thinking behind the firm’s most innovative designs – including Lloyd’s of London and the Leadenhall Building – and explains why building services engineers are more important than ever to high-quality architecture.

Career to date

Mike Davies has worked with Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners for more than 35 years, and has been involved in virtually all of its projects. Born in Wales in 1942, he started his career at Airstructures Design, in London, while studying at the Architectural Association. He graduated with a Master’s in Urban Design from UCLA, and worked for six years on the Pompidou Centre before becoming a founding partner in the Richard Rogers Partnership in 1977. He was project director both for the Millennium Dome and Heathrow Terminal 5. Davies was made a CBE in 2000 and was appointed a Chevalier of the Order of the Légion d’honneur in 2010.

The unlikely traditionalist

With his long, grey beard and stark red suit – he never wears any other colour – 72-year-old Davies has the air of a sixties radical. But it turns out that, in some ways, he is quite the traditionalist. Take the Lloyd’s building, which Rogers designed in the early 1980s. Although the stairs, lifts and pipework are located in six vertical towers on the outside of the building, the positioning of the towers was not down to chance, but to ideas set out a century earlier.

‘The location of each tower is significant,’ says Davies. ‘If you look down any side street, in the gaps you will see the service towers, rather than the building itself – just like in Victorian London, where corners were celebrated and you didn’t see blank walls.

‘In many ways, Lloyd’s of London is a traditional building. Can you think of any Victorian building where you turned a corner without any celebration? I can’t. So it continues in the tradition of London, of celebrating corners – and these small side streets display an urban tapestry.’

Davies says it was important to Lloyd’s that the centre of its dealing operations – The Room – would provide for its needs well into the next century. Rogers responded by creating a series of galleries that could expand – and contract – around a central ‘market’ space, with escalators and external glazed lifts providing easy access between floors. ‘The client was aware of how valuable space is in a city like London, and did not really want people in white coats or blue dungarees carrying out maintenance work in the building – so we put the services elsewhere.’

All the modular mechanical services – lifts, kitchens, fire stairs, lobbies and toilets (which were made in Bristol) – were housed in six service towers, easily accessible for maintenance. In fact, you can strip off a whole service tower and completely rebuild it without closing the insurance market, says Davies.

Lloyd's service towers are visible from London's side streets

‘It’s not to wind people up’

The Lloyd’s building’s 84m-high internal atrium owes something to the Crystal Palace, while the use of opaque glass pays homage to Pierre Chareau’s Maison de Verre, in Paris. And talk of Paris, inevitably, brings us back to the Pompidou.

With its exposed skeleton of brightly coloured ducts and pipes, the Pompidou had to be tall enough to accommodate 90,000m2 of space. Here, for the first time, services systems enveloped the external elevation, their distinctive colour-coded finish displayed for the world to see. Contrary to popular opinion, Davies says this was not to provoke shock.

‘The fact that the ducts are on the outside is a technical aspect – it’s not for aesthetic reasons, to wind people up. We wanted a neutral, social space, with people on one side and technical services on the other,’ he says. ‘You do not need to put services indoors. If you put a reasonable finish on them, there’s no reason why they should take up internal space.’

As for their colouring, the architects followed the French code, with different colours representing the different fluids that the pipes were carrying. The colours have faded over the years, but the shock factor of the façade certainly hasn’t – even if the building has gained sufficient respectability in its old age for Davies to have been appointed a Chevalier of the Order of the Légion d’Honneur by Nicolas Sarkozy, in 2010.

The building demonstrates a remarkable degree of craftsmanship in the way the detailed structural elements fit together. The modular components and connections comprise 16,000 tonnes of cast and prefabricated steel elements that were delivered by truck at night. This suggests the Pompidou owes as much to the Victorian engineering tradition as to the space age.

Davies says that, in spatial terms, it uses a ‘served-and-servant’ concept: the building is served by people services at the front, with servant spaces – the spaces that serve other spaces, such as stairwells, corridors and toilets – at the back. The aim was to enable services to be modified over time without disrupting existing operations.

The buildings are alive…

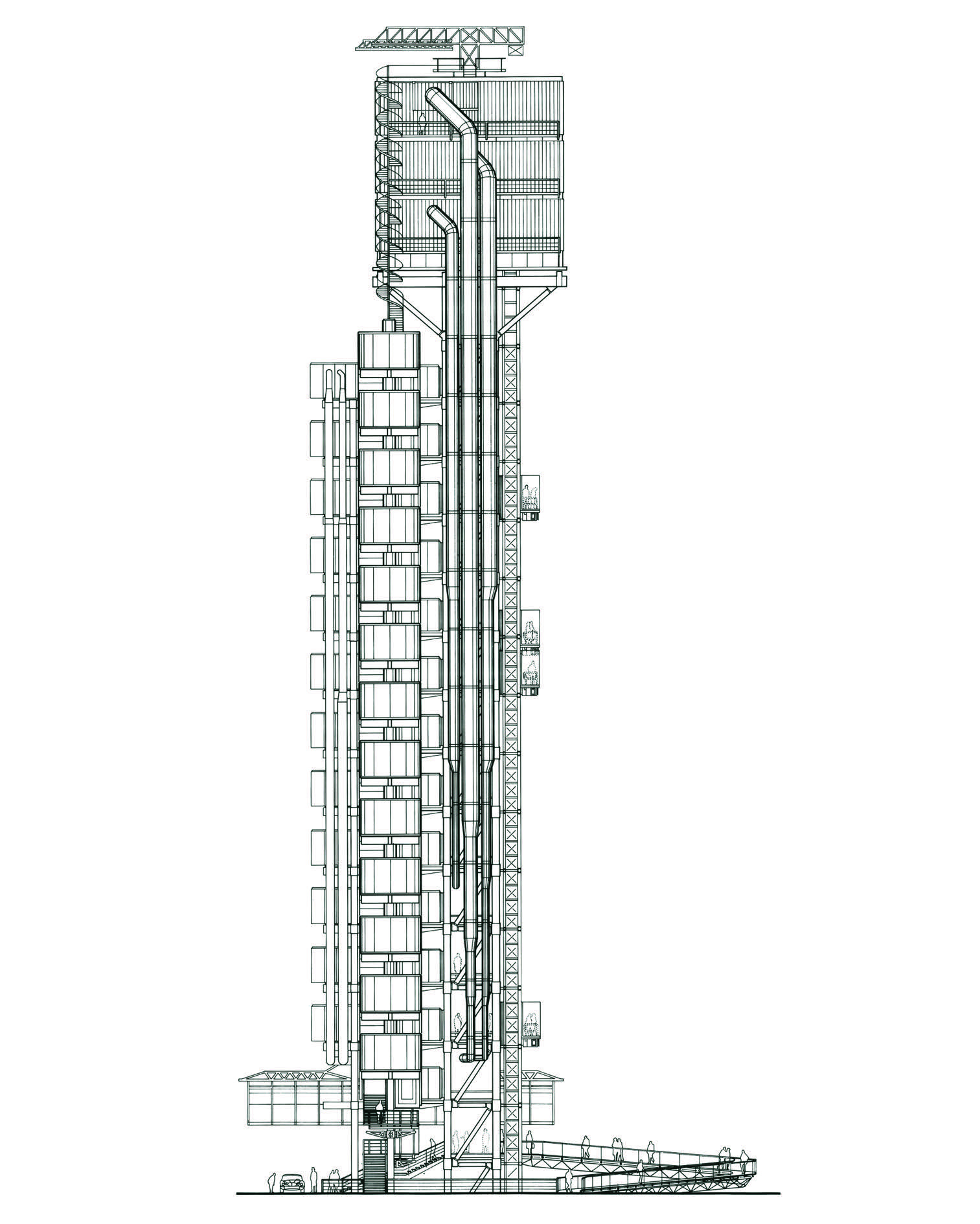

Lloyd's towers house pre-fabricated components

A large part of the Leadenhall Building, in London – Rogers’ most recent project, due to be finished this year – is also prefabricated. It has a ‘dynamic’ façade, with the sides that face the sun in the morning being the energy generators, and the north side the energy loser.

The building has a triple-skin façade, with a single skin outside and an internal layer of double-glazing on the façades to the office areas. The external glazing incorporates vents at node levels – allowing outside air to enter and discharge from the cavity between the glazing – while controlled blinds automatically adjust to limit unwanted solar gain and glare.

Clearly, future-proofing has always been an important part of the process for Rogers, as the designs for the Pompidou and Lloyd’s show. Davies says buildings should be flexible and adaptable, as he highlighted in his CIBSE Building Performance Awards address, in which he described a future building that automatically adapts to its surroundings. Not that it’s all that futuristic, he points out.

‘Afterwards, someone said to me, “I like your science fiction bit” – but it’s not science fiction. If I had met you in the street in 1966 and told you that, in 30 years’ time, anyone in the world would be able to share knowledge with someone else through a virtual system – and be able to drive cars that map their way around – you would have said: ‘Forget it’. Pieces of what I was describing already exist – it’s further ahead than we think.

‘My vision for the future is buildings that are alive and self-aware – aware of their users’ needs, responding to their environment, adjusting to day and night conditions, planning ahead and being as carbon neutral as possible. And it’ll all be automatic.’

These are not new ideas for Davies. In 1981, he proposed the concept of a multiple-skin envelope – a self-adapting, energy-generating, multilayered, multi-property façade sandwich as a live and interactive, intelligent building skin. ‘It was a radical idea at the time and is still not quite with us, but all of its ingredients are now here,’ says Davies.

‘I envisage the day when the façades of our modern buildings – and their internal building services – become symbiotic intelligent systems, where the skin of the building becomes the principal processing and control mechanism for comfort and energy efficiency.

‘The advanced buildings of the next decades will be chameleons – continually responding, intelligently and appropriately, to external environments and internal user needs.’

Rattling cages

Davies says the designers of these chameleons, alongside architects, are services and structural engineers. ‘The industry has got its superstars beginning to emerge, making waves in sustainable issues, building smarter buildings and striding forward.’ As new and renewable technologies become the norm, we’re ‘beginning to put our money where our mouth is as a nation’, he adds. ‘The services industry will continue to be champions for that.’

Davies believes engineering advice must be sought early in the design process. At Rogers, there is almost always an engineer present at the firm’s weekly, open design reviews. ‘Architectural intent, function and structural, services and environmental intent – all need to be brought together at an early stage to achieve the aesthetic, functional and civic integrity of a good building.’

Architectural highs

A selection of groundbreaking projects designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners over the last 35 years. Davies was project director on the Millennium Dome.

1977 – Pompidou Centre in Paris

1986 – Lloyd’s of London

1995 – European Court of Human Rights

1999 – Millennium Dome

2014 – The Leadenhall Building

Environmental and energy concerns mean services engineers have shed their ‘backroom boy’ image and been propelled to the sharp end of the design process. ‘More and more we need to be talking with services engineers about the design to invest in it environmentally. Not all clients understand that if you set environmental conceptual parameters correctly, you partly solve that problem at the beginning of the process.

‘Services engineers need to rattle the cages to get closer to contractors and architects in the early stages of a project. I cannot think of a better career than services engineering – it’s a valuable, important, and interesting field.’

One area that needs addressing is female participation in the sector. Although the situation is better than it has ever been, Davies believes more needs to be done to encourage women to join the ranks. ‘Traditionally, it has been incredibly difficult for women who start a family to do that.’

Architecture is far more progressive in this respect: at Rogers, 43% of the architects are women, and, overall, women make up 37% of the staff. ‘An all-male office cannot function properly,’ says Davies. ‘It should represent a normal intersection of society.’

Such a view might have seemed radical 40 or 50 years ago, but society is gradually catching up. In a way, such progress encapsulates Davies’ and Rogers’ careers – their high-tech designs were never that outlandish; they just reached the future before everybody else.