Globe Point in Leeds was named Project of the Year - New-build Workplaces at the 2025 CIBSE Building Performance Awards

What does it take to deliver buildings that perform in practice? Each year, the CIBSE Building Performance Awards put that question to the test, with submissions providing detailed evidence of how projects operate once occupied.

Our annual review of entries has become a vital barometer of building performance, offering insight into energy use, indoor environment and delivery practices. Since 2021, a standardised data form has raised the quality and consistency of submissions, allowing meaningful benchmarking across projects. The data informs updates to awards categories, and helps CIBSE’s contribution to initiatives such as the UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard (UK NZCBS).

This year’s analysis shows marked improvements in the reliability of energy data and wider uptake of post-occupancy evaluation (POE), with many projects’ energy use being well below the national average. At the same time, challenges remain – particularly around onsite renewable reporting, district heating, embodied carbon, and refrigerants.

Quality of the data

The analysis confirms that the quality and scope of building performance data keeps increasing, with fewer areas of data uncertainty and wider coverage of building performance.

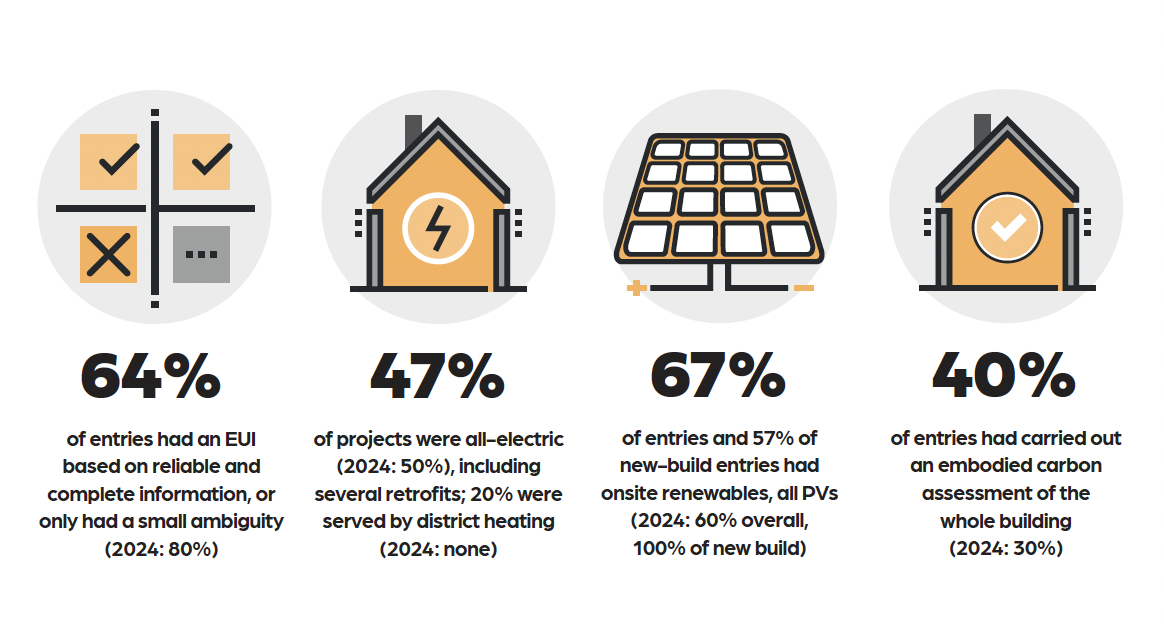

The majority of entries show data that is complete and reliable enough to estimate energy use intensity (EUI) with reasonable confidence, or with only a small level of uncertainty (64%). This is a marked increase from a few years ago.

An important caveat relates to onsite generation: photovoltaics (PVs) were present in more than half of the project entries and, for many of these buildings, some uncertainty was reported over the amount of renewable energy generated on site and/or used by the building. There was either no information available, or only the total generated was known, not the portion used by the building. This meant a full EUI could not be established. District heating also limited assessment of the full EUI, as, typically, only the heat delivered was provided, not the full energy used to generate and distribute that heat.

Apart from that, essential information that tended not to be available was annual water use and peak electricity demand. This was expected because these metrics are less commonly gathered, and it was only last year that this was deemed essential information in the data form.

What the data tells us

As in the previous year, the new-build entries, and several retrofit entries, tended to have much lower energy use than the average building stock, sometimes significantly. While only a high-level comparison is possible, some projects – both new build and retrofit – were close to or met the UK NZCBS Pilot energy-use limits.

Building footprint information was required for the first time this year, to benchmark renewable energy generation against targets in the NZCBS. This will be reported in the Journal once a large enough sample of data is available.

The data forms also request information on whether an embodied carbon assessment has been carried out for the whole building (and, if so, the results), whether building services were included in the assessment (and, if so, the methodology used), and details on refrigerants.

Project of the Year entries need at least one year of operation, so they reflect design practice from several years ago. As a result, only around 40% of entrants stated that they had carried out a whole building embodied carbon assessment. Similarly, where information on refrigerants is available, it relates largely to refrigerants of relatively high global warming potential (GWP), such as R410a and R134a, compared with the latest R32 (where the UK NZCBS Pilot limit is pegged) or other low-GWP refrigerants.

Interior of the Entopia Building, the overall champion at the 2025 CIBSE Building Performance Awards

What the data tells us on project delivery

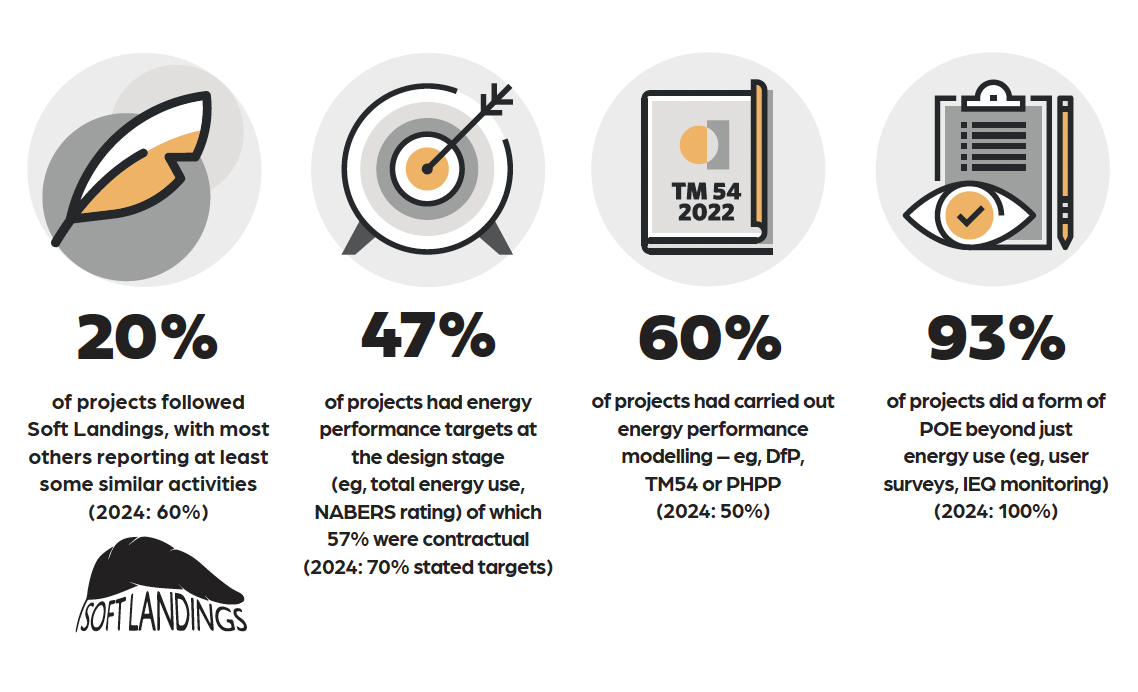

The majority of projects used energy performance modelling, rather than just compliance modelling. For example, CIBSE TM54, Passivhaus Planning Package (PHPP) or the Design for Performance (DfP) framework, which is used for NABERS UK. Many also set energy performance targets – rather than regulatory ones – such as EUIs, NABERS UK ratings and Passivhaus/Enerphit targets. Some of these were contractual targets.

Most projects carried out POE. As well as energy use, indoor air quality, temperature monitoring and occupant surveys were seen among the entries. In recent years, CIBSE has broadened the eligible time bracket for projects, to reflect longer periods (2-3 years) of monitoring and fine-tuning when consultants remain involved to improve building performance.

Commercial picks up performance baton

Compared with previous years, when entries were dominated by owner-occupier buildings, there was a significant increase in the number of submissions from the commercial sector, including from speculative multitenanted buildings, industrial parks, and portfolios. This indicates a positive trend towards more reporting, disclosure and landlord-tenant collaboration on building performance. Similarly, the majority of entries in the domestic sector were from multiresidential schemes, rather than individual homes or very small schemes.

Ensuring building performance and collating data can be challenging in these sectors, and entrants reported a mix of measures to address the challenges. These included intensive liaison between the developers/owners and the commercial tenants/residents, from the strategic levels (to align corporate objectives) through to the fit-out teams, building managers and occupants. There were also longer periods of handover, occupant surveys and fine-tuning, with regular feedback to occupants.

The use of technology was also prevalent, including real-time energy monitoring, live apps to report faults in services and metering equipment, and remote indoor environmental quality sensors in residential units.

Entrants were keen to highlight the benefits of these approaches, with positive occupant feedback, as well as energy performance improvements. The Portfolio winner, Cathedral Hill Industrial Estate, reported a 220% increase in rental value following its decarbonisation works.

Future awards entry forms will seek to gather more information, to share lessons with the wider industry and reward teams that manage to address these sectoral challenges.

Analysis of 2025 entries

Evolution of the Building Performance Awards

There are two new categories on Building Performance Evaluation for the 2026 awards: one for practice and one for technical solutions.

A new Portfolio category, under Project of the Year, reflects the growing number of entries of this type, and the specific efforts and solutions they call for.

Changes to the Project of the Year data collection forms for 2026 include:

- More information on refrigerants’ impact, including GWP, charge, and leakage if known

- Information on the building footprint where there is onsite generation, to allow benchmarking against the UK NZCBS targets

- More information on embodied carbon assessments

- Water consumption is now deemed essential (rather than optional) information, to reflect increased pressures on water supplies, particularly in the South East

- More information on peak demand is now also included in essential information. This reflects increased attention to demand management as buildings electrify

- If information is not available, entrants have the option to simply say so.

The 2026 CIBSE Building Performance Awards are now closed for entries, and will take place on 5 March 2026 at the Park Plaza. For more information, visit: www.cibse.org/bpa