The 2025 CIBSE Technical Symposium saw a significant shift in the conversation around artificial intelligence, with a session on AI and parametric tools: transforming design and collaboration demonstrating how far the industry has come in just a year. Chaired by Darren Coppins from Built Physics, the panel brought together leading voices who showcased practical, pioneering uses of AI, not just as a concept, but as a functional design partner reshaping how we build, manage, and collaborate.

Making NHS guidance intelligent

Carl-Marnus Von Behr from the University of Cambridge opened the session with a compelling presentation on a domain-specific AI tool designed for NHS estates teams, where information overload can compromise efficiency and safety. ‘Locating the right information can often feel like searching for a needle in a haystack,’ he said a NHS Director of Estates had reported, supported by research showing staff spend an average of 11.35 hours per week trawling through fragmented documentation.

Von Behr explained why conventional AI tools fall short in this environment: ‘Generic models struggle with the NHS’s domain complexity and inconsistent jargon.’ His solution was to create a tailored AI model trained on NHS-specific regulations and language, capable of delivering precise, sourced answers.

In a pilot with 62 estate staff, the tool cut search time by 35% and improved answer quality by 53%. ‘Interestingly, younger users saved more time, while older users saw more accurate answers,’ Von Behr noted, arguing that AI can bridge gaps in experience and institutional knowledge.

‘This isn’t just about saving time,’ he stressed. ‘It’s about enhancing safety, compliance, and collaboration in a sector under enormous pressure.’ He shared that future iterations of the platform aim to automate policy writing, flag skills gaps, and streamline training, creating an intelligent support system for NHS operations.

AI in design tools

Andrew Corney and Dan Scofield from Trimble SketchUp followed with a look at the current capabilities and limitations of AI in building simulation. ‘From geometry interpretation to climate analysis and generative storytelling, AI is helping us model performance in entirely new ways,’ he said. However, Corney was quick to point out its blind spots, ‘If you don’t tell AI what the context is, it will embed its own.’

‘We essentially created a software product that takes weather data and uses defined calculations to convert it into advice about solar gain, overheating risks, or optimal shading,’ Corney explained. This traditional ‘knowledge-based’ approach, where rules are predefined, forms the backbone of many energy simulation tools. However, it comes with constraints. ‘The problem is, every time you hit an exception, you have to write a new rule,’ he said. ‘It’s hard to go beyond the questions the system is explicitly designed to answer.’

To address these limitations, Corney’s team introduced machine learning into the SketchUp pipeline. The new AI-driven tool categorises spaces, even in loosely structured models, using heuristics based on geometry and context. ‘SketchUp traditionally doesn’t classify spaces. This tool can extract and label rooms from unstructured geometry, even when furniture and clutter are in the way,’ Corney noted.

The system combines two approaches: one uses CLIP, an off-the-shelf image-based AI model, to identify objects based on thumbnails. The other uses a point cloud-based AI model trained to segment and classify building components like slabs, walls, and roofs in three dimensions. ‘CLIP works well for small objects; point cloud is stronger for larger architectural elements. Together, they give us about 80% accuracy—and save engineers up to 80% of the time they’d otherwise spend classifying models manually.’

For Corney, AI’s true potential lies in augmenting, not replacing, human expertise. ‘Just as coders now guide AI as copilots, designers will become strategic conductors rather than manual draughtsmen,’ he said.

But this shift brings a warning. ‘If junior engineers rely too heavily on AI, will they ever learn to do it themselves?’ The danger isn’t in AI doing too much, it’s in humans doing too little, he explained.

‘Disruption is inevitable,’ he concluded. ‘Our challenge is to shape how AI enhances, not erodes, human capability.’

Integrating Sustainability from the Start

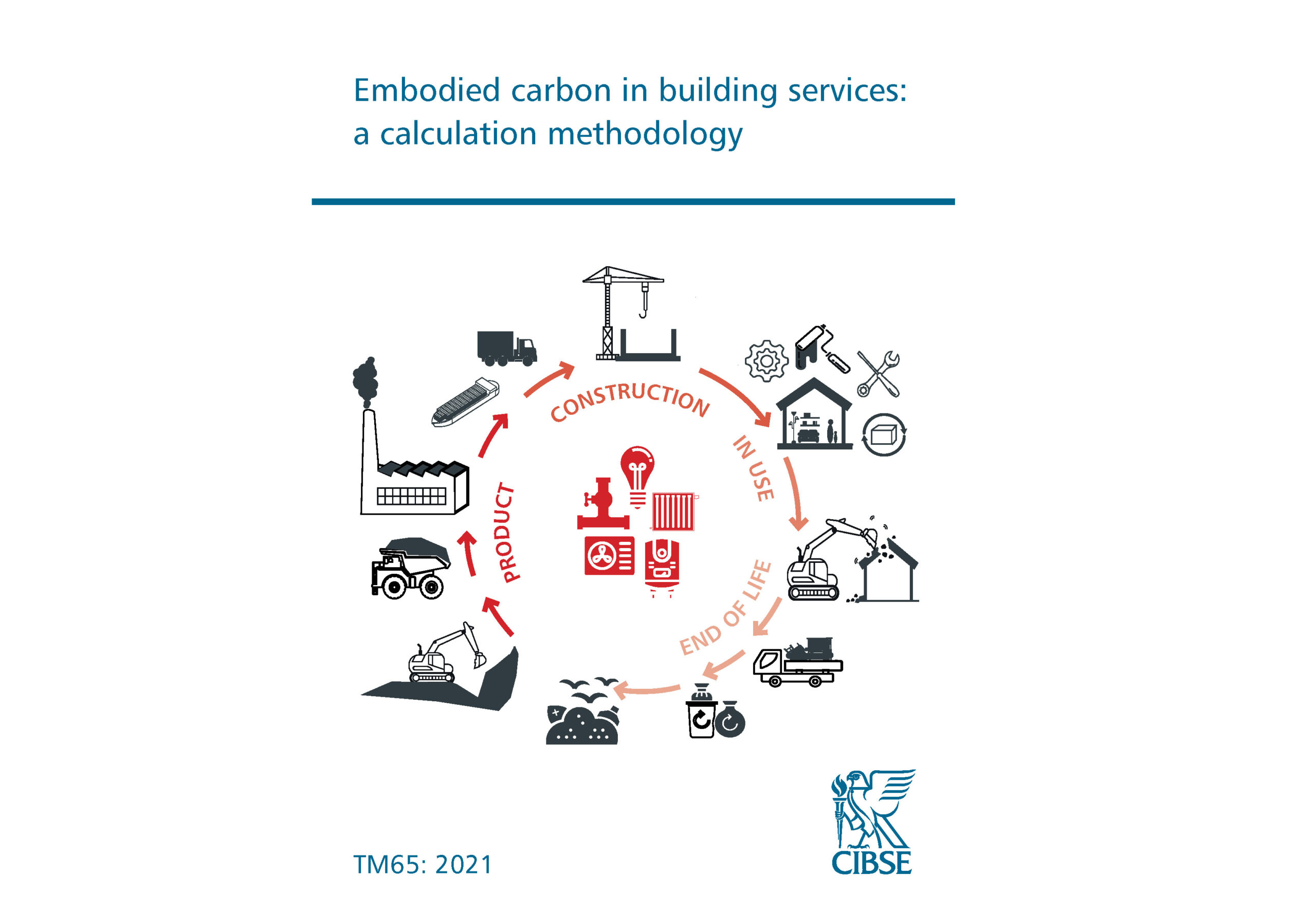

Ines Idzikowski from AECOM presented a sustainability-focused parametric design tool trialled on a hotel project in the mountainous north of Madrid. The site posed several challenges – harsh summer heat, water infrastructure limits, and strict building regulations, all of which demanded a more intelligent design process from the outset.

‘Environmental design used to focus mainly on energy, but it’s now about whole-system KPIs,’ Idzikowski explained. ‘Embedding sustainability early makes it both more impactful and more cost-effective, but it’s hard to manage conflicting priorities without digital support.’

Instead of following the typical linear process, where environmental analysis is bolted on after key design decisions, the team created a circular, real-time workflow driven by a modular parametric dashboard. Built in Grasshopper and Ladybug, the tool enabled live scenario testing for embodied carbon, operational energy, water efficiency, and cost, all of which could be viewed and adjusted interactively.

The tool consolidates these design parameters into a single visual dashboard. The team used it to create and evaluate ‘baseline,’ ‘good,’ ‘better,’ and ‘best’ design scenarios in real-time with clients and engineers. The result was a 36% reduction in upfront embodied carbon and improved water reuse strategies, without derailing the budget.

Idzikowski explained that this required front-loading a significant amount of data work: gathering material carbon footprints, regional cost benchmarks, and climate data, and engaging deeply with the client, architects, and engineers to co-define feasible options. Prebuilt toolkits were customised and expanded to reflect project-specific decisions, from glazing ratios to water reuse systems.

Using this dashboard, the team could rapidly evaluate design trade-offs. For example, they assessed different façade materials (compressed earth blocks, timber, etc.), structural strategies, glazing areas, and even pool sizing.

‘We found that visual tools made sustainability tangible,’ said Idzikowski. ‘They helped our clients engage and make informed decisions early in the process.’ The project, now out for tender, is a testament to how parametric tools can guide complex, sustainable design from vision to execution.

Reflections

‘If we let AI does all the simple tasks, we risk losing fundamental skills,’ warned Corney. ‘We need to stay capable even as we automate.’ The room agreed: AI should be a tool, not a crutch.

Chair Darren Coppins summed it up: ‘Last year we were speculating about AI. This year, we’re seeing it used in real projects. The question is no longer if it will change our industry—but how we make sure we stay in the driver’s seat.’