CPD sponsor

This CPD article builds on the March 2024 CIBSE Journal CPD module 230, which introduced the basic principles of chemical-free water treatment (CFWT) and the operation of demineralisation and reaction-tank systems. This module now examines the wider application of those principles across the commissioning, operation and conversion of closed-loop heating and cooling networks, drawing on the new Commissioning Specialists Association (CSA) Technical Memorandum 20 (TM20).

CFWT has matured from a promising alternative into an engineering-led method that aligns with current European and UK practice for closed-loop heating and cooling systems. The fundamental challenge is that water is never just water. Left untreated, it can carry oxygen, dissolved salts and ions – such as chlorides, sulphates and nitrates – minerals, microbes and dissolved carbon dioxide that can slowly impact the longevity of system components designed for long operational lifetimes.

Even small deviations in water quality can set off a chain of consequences: corrosion that produces sludge and pinhole leaks; scale that lowers efficiency and increases pumping energy; and microbiological growth that fosters biofilms and microbially induced corrosion (MIC). Chemical inhibitors, dispersants and biocides have historically been the conventional remedy, coating metal surfaces, suppressing microbes and controlling scale. But chemicals bring their own challenges, with the need for regular dosing, testing and replacement, safety risks in handling and storage, incompatibility with materials or microbes, and environmental consequences when discharged.

Stable and protective environment

CFWT aims to create a stable and protective water environment without introducing additives. Instead of relying on films and inhibitors, CFWT manages the fundamental variables that drive corrosion and fouling – dissolved oxygen, electrical conductivity and pH balance. When these three parameters are controlled within defined limits, the water becomes naturally benign to system materials. This philosophy underpins the new CSA TM20,1 which establishes guidance for the design, commissioning and maintenance of CFWT systems in closed-loop heating and cooling networks. The new guidance aligns with European frameworks such as VDI 20352 for heating and VDI 60443 for cooling, together with BS EN 128284 for system design, and complements existing UK documents, including BSRIA BG 295 and BG 506, and CIBSE CP1 Heat Networks: Code of Practice.7

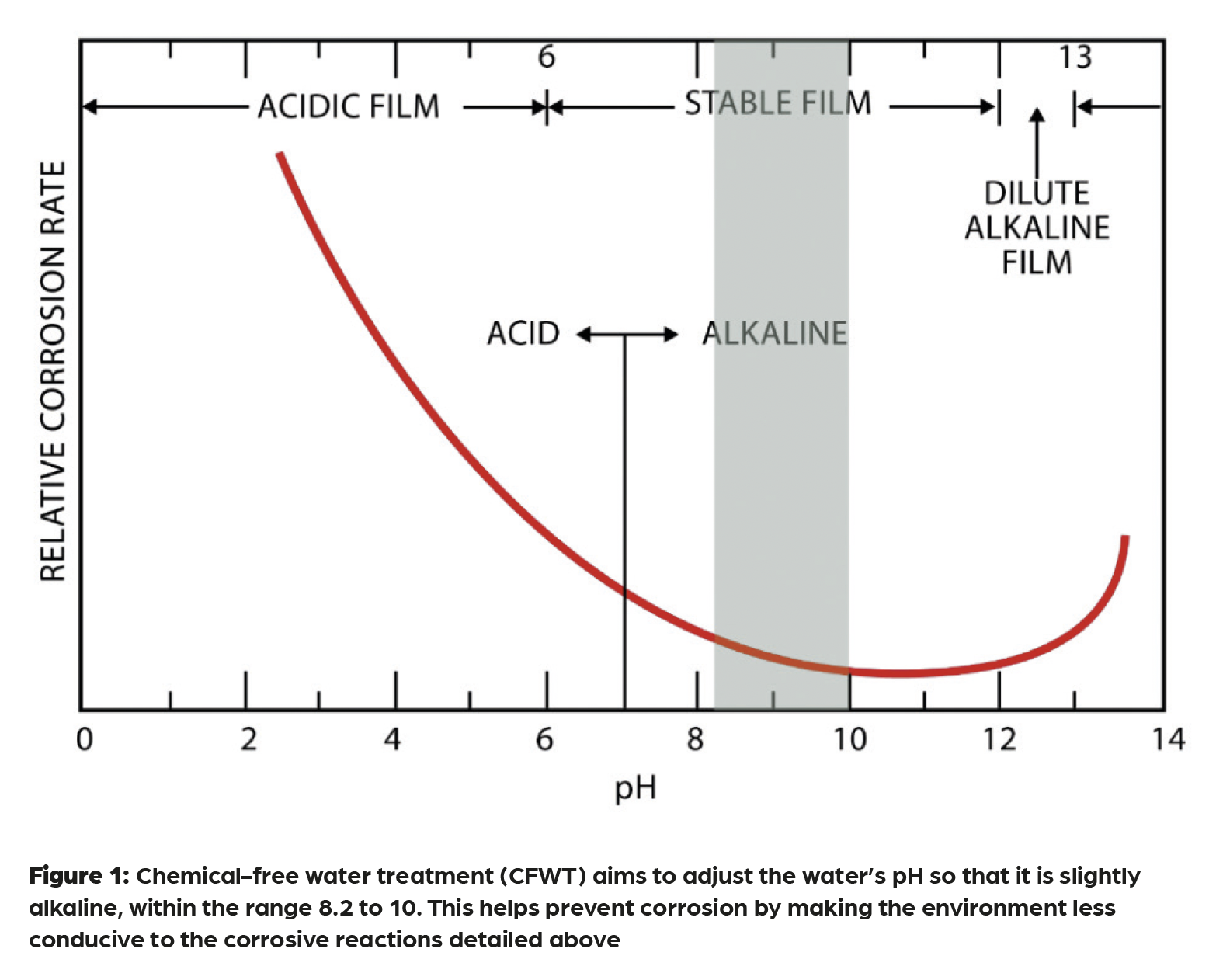

Corrosion is a key issue with closed-loop hydronic systems. It is the natural tendency of metals to revert to their stable, oxidised state – rust in steel and tarnish in copper. In heating and cooling loops, the rate of this reaction is accelerated by several factors. The most significant is dissolved oxygen, a potent oxidising agent that fuels electrochemical reactions. The second is the concentration of dissolved salts and minerals, reflected by the water’s electrical conductivity, which determines how easily ions can carry charge between anodic and cathodic areas. The third is pH, as acidic or excessively alkaline water destabilises protective oxide films. These three form the causal trinity of corrosion. Added to these are the effects of temperature, velocity and microbial activity, particularly from sulphate-reducing and nitrite-reducing bacteria that thrive when nutrients such as sulphates or nitrites are available.

Demineralisation and electrochemical oxygen scavenging

Traditional inhibitor regimes attempt to slow these processes by forming protective films and suppressing microbial growth. CFWT takes a different approach. Rather than compensating for corrosion, it eliminates the conditions that make it possible.

In practice, CFWT relies on two complementary technologies – demineralisation and electrochemical oxygen scavenging. In the first, ion-exchange resins remove dissolved salts and minerals from fill and make-up water. Cation resins exchange positively charged ions such as calcium and magnesium for hydrogen ions, while anion resins exchange negatively charged ions such as chlorides, sulphates and nitrates for hydroxide ions. The result is water that is low in conductivity (typically below 100µS.cm–¹) and free from hardness and most nutrients that bacteria require. This demineralised water is poor at conducting electricity and does not support limescale deposition.

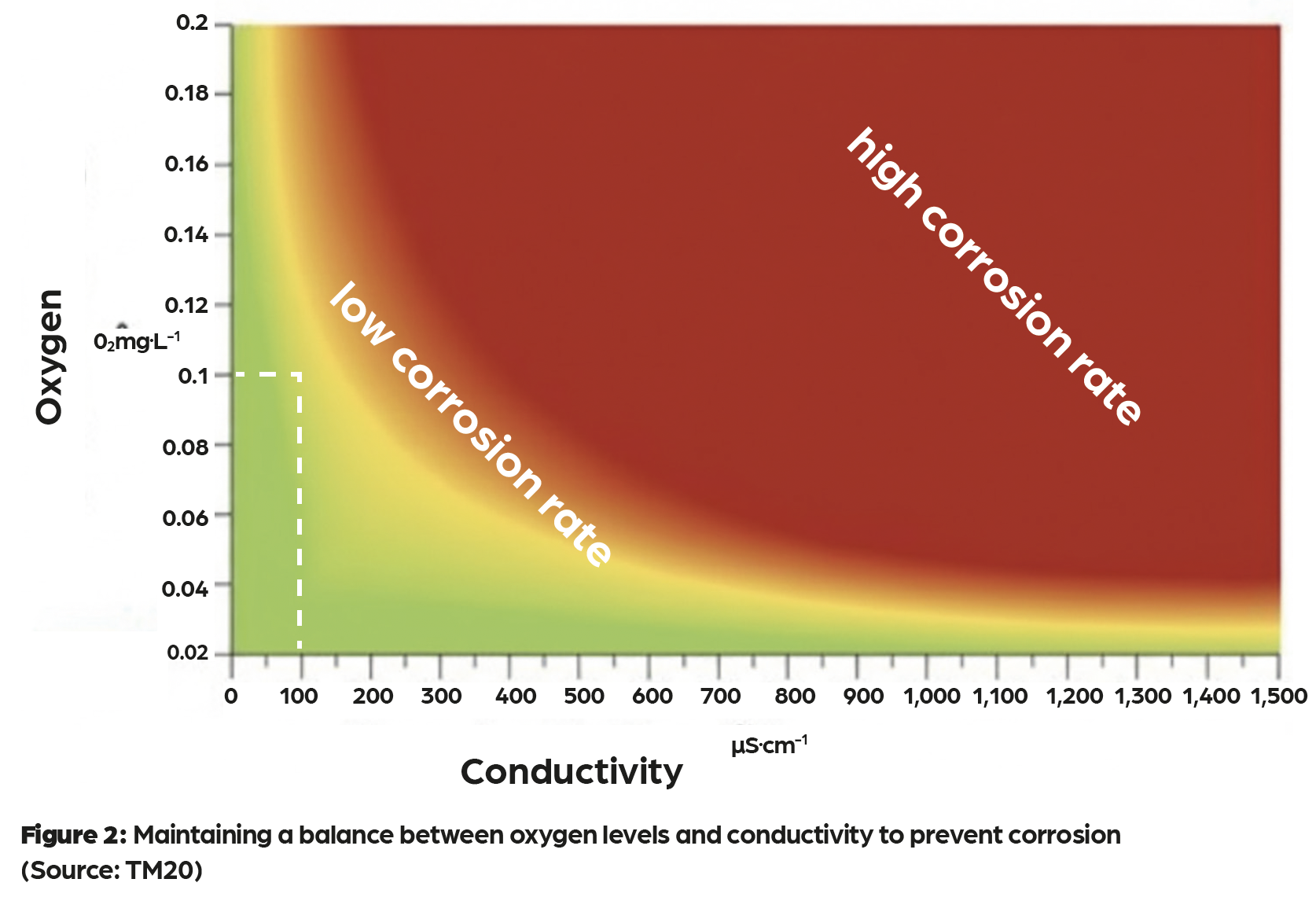

The second technology is the reaction tank, which carries out electrochemical oxygen scavenging. The tank houses sacrificial magnesium anodes mounted within a stainless-steel body and filter assembly that act together as an electrochemical cell. When oxygen is present, the magnesium preferentially corrodes, consuming oxygen and producing magnesium hydroxide, which raises and stabilises the water at a slightly alkaline pH. In oxygen-free conditions, the anodes lie dormant and can last for several years. When oxygen enters through make-up water or maintenance, the reaction automatically restarts, maintaining equilibrium (as indicated by the area bounded by the white dashed lines in Figure 2) without chemical dosing.

The demineralisation and reaction-tank arrangement were described in CIBSE Journal CPD module 230, and remains at the heart of the system. In essence, the process water passes through a mixed-bed resin vessel to remove ions before circulating through a stainless-steel side-stream reaction tank fitted with magnesium anodes, filters and an air vent. Together, they continuously remove oxygen, gas bubbles and fine debris, stabilising both the chemistry and micro-environment of the circuit.

The conditions promoted through CFWT are already embedded in European practice. VDI 2035 and VDI 6044 specify the same goals – low dissolved oxygen, low conductivity and a mildly alkaline pH – as the preferred means of preventing scale and corrosion, without reliance on inhibitors. BS EN 12828 and many manufacturer warranties now echo these targets. In the UK, BG 29 and BG 50 focus on verifying water quality rather than residual chemical concentrations, and CIBSE CP1 reinforces the importance of controlled filling and monitoring. TM20 extends these principles into a defined process for both new installations and legacy conversions, giving engineers a consistent language for specifying and commissioning chemical-free systems.

New systems

For new systems, the conditions of the initial fill are critical. TM20 follows the familiar sequence of BG 29 but changes the chemistry: fill slowly and methodically from the lowest point with demineralised water that has low bacterial levels and controlled pH, produced by mobile mixed-bed units that also remove carbon dioxide. The aim is to prevent trapped air, as even small oxygen pockets can localise corrosion. Dynamic cleaning then circulates the water at velocities high enough to mobilise debris, using either full-flow or side-stream filtration (as discussed in CIBSE Journal CPD module 230). TM20 suggests a minimum of the BG 29 values or the design velocity plus 10%, whichever is greater. Differential pressure gauges across filters help indicate when cartridges need replacement, avoiding unnecessary shutdowns.

Once debris has been removed, a polishing phase brings conductivity below the 100µS.cm–¹ benchmark using resin filtration. The cleaned and de-aerated water is then ready for circulation. The principle is that once wet, the system is kept wet. Systems filled with demineralised water should not be drained, as draining reintroduces oxygen and resets corrosion potential. TM20 recommends sampling and laboratory verification at each stage to confirm that physical parameters meet target values. Onsite testing should be used for routine checks, supported by laboratory analysis for confirmation, ensuring a rapid workflow without compromising quality assurance.

Figure 3: Example of a mobile demineralisation unit that can be installed in line with the mains water supply and the system connection. This process effectively removes minerals and salts, while also raising the pH to optimal levels. A resin used in this particular unit removes carbon dioxide and raises the water pH (Source: IWTM)

Existing systems

For existing systems already operating under chemical regimes, CFWT can be introduced progressively. Progressive system improvement is less disruptive than a complete system renewal and often preferred where continuous service is required. In this approach, demineralisation and reaction tanks are installed as side-stream devices, using either existing system pumps or a small integral pump to maintain circulation. Over several weeks, dissolved oxygen is consumed, pH stabilises and conductivity gradually falls as contaminants are filtered out. Filter cleaning and periodic blowdown (the controlled discharge of a small volume of system water) helps maintain water clarity and prevents the build-up of corrosion products and magnesium hydroxide, keeping the system clean and stable. TM20 acknowledges that achieving the same conductivity targets as for new systems may not always be realistic, but if oxygen and pH are well controlled, slightly higher conductivity is acceptable because the water corrosivity is low. The optimal range for pH control is shown in Figure 1.

Environmental conditions

Microbially-induced corrosion often arises from sulphate-reducing bacteria (SRB) that produce hydrogen sulphide, which pits steel, and nitrite-reducing bacteria (NRB) that generate ammonia, which attacks copper alloys. These organisms depend on specific environmental conditions – SRB require sulphates and thrive under anaerobic, low-pH conditions, while NRB need nitrites and oxygen. CFWT suppresses both by removing nutrients through demineralisation and maintaining an oxygen-poor, alkaline environment. The reaction tank consumes oxygen and elevates pH into a range (typically 8.5-9.5) that is unfavourable to both species. In new systems, this prevents colonisation; in existing ones, bacterial counts gradually decline as the water becomes inhospitable. TM20 advises using total viable count (TVC) and SRB testing as practical indicators during transition, as NRB are more difficult to measure directly.

In CFWT applications, operators monitor three parameters – conductivity, pH and dissolved oxygen – using handheld or inline meters. Ion-exchange resins are replaced when conductivity rises above the agreed threshold, and magnesium anodes typically last about three years in well-sealed systems. Regular blowdowns and filter cleaning remove sludge and magnesium hydroxide residues. Inline galvanometers or visual indicators on reaction tanks reflect the anode status. The maintenance cycle is typically predictable.

Reducing risks

CFWT eliminates the handling, transport and disposal of hazardous chemicals, reducing risks to health, safety and the environment. It also removes the uncertainty of chemical interactions, and the carbon impact associated with inhibitor production and delivery. Systems operating under stable, low-conductivity conditions have been demonstrated as having improved heat-transfer efficiency and lower maintenance costs. From an operational perspective, CFWT simplifies compliance with environmental standards and sustainability goals.

As with any engineered process, CFWT depends on good design and disciplined commissioning. Loops must be properly vented, leak-tight and free-flowing; stagnation or air ingress will defeat any treatment method. Legacy systems may need patience while residual chemistry decays and the conductivity stabilises. Consumables such as resin and anodes require routine attention. Yet, with these understood, CFWT has proved robust in diverse applications, including hospitals, data centres and district energy networks.

Mainstream standard

CFWT is well positioned to move from alternative practice to the mainstream standard. In parts of Europe it is already the norm, supported by frameworks such as VDI 2035 and 6044. In the UK, the publication of CSA TM20 provides a significant milestone, mirroring the influence that BSRIA BG 29 once had on conventional chemical treatment. By establishing a unified process and clear water-quality benchmarks, TM20 gives specifiers and operators a consistent basis for design, commissioning and maintenance.

For engineers and system operators, CFWT represents a practical evolution in closed-loop water management. By addressing the root causes of corrosion and fouling through controlled water chemistry, it offers an opportunity to maintain stable, low-risk operation while reducing environmental impact and simplifying maintenance requirements.

© Tim Dwyer 2025.

References:

1 Commissioning Specialists Association (CSA) Technical Memorandum 20: Guide to chemical-free water treatment for closed-loop heating and cooling networks’, CSA July 2025.

2 VDI 2035 – Prevention of damage in water heating installations – Scale formation and waterside corrosion, VDI 2021.

3 VDI 6044 – Prevention of damage in cold and cooling water circuits, VDI 2023.

4 BS EN 12828:2012+A1:2014 – Heating systems in buildings: design for water-based heating systems, BSI.

5 BSRIA BG 29/2021: Pre-commission cleaning of pipework systems (amended 6th edition), BSRIA 2021.

6 BSRIA BG 50/2021: Water treatment for building services systems, BSRIA 2021.

7 CIBSE CP1: Heat networks – Code of Practice for the UK (2nd edition), CIBSE 2020.