CPD sponsor

In response to the climate crisis, many organisations that monitor and report their carbon emissions are placing increasing pressure on hotels to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions associated with their operations. This reflects those organisations’ drive to reduce Scope 3 emissions from indirect business activities, including the accommodation of staff during business travel.

Hotels are also under scrutiny from the growth of eco-tourism and from booking providers that highlight sustainability credentials.

In the UK, it is estimated that the average amount of carbon emissions generated per occupied room per night in hotels1 is 10.4kgCO₂e, rising to 11.5kgCO₂e in London.2 Major hotel brands have made commitments to address this.

For example, the Radisson Hotel Group has committed to a science-based net zero target for 2050,3 while the Accor group has set the same long-term goal, with interim objectives of reducing Scope 1 and 2 emissions by 46%, and Scope 3 emissions by 28% by 2030,4 relative to a 2019 baseline.

As part of their emissions-reduction strategies, many hotel groups are focusing on their existing assets rather than replacing them with new builds. Many refurbishment projects can offer significant operational carbon savings compared with demolition and reconstruction.

Within these refurbishments, replacement or upgrading of heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems is often a priority. In some cases, this involves moving from older variable refrigerant flow (VRF) systems to newer, more efficient models using refrigerants with a lower global warming potential (GWP).

VRF: a quick refresher

Variable refrigerant flow (VRF) technology is a modular HVAC solution that uses refrigerant as the primary heating and cooling medium. A single outdoor condensing unit serves multiple indoor units via a network of refrigerant piping, with each indoor unit delivering heating or cooling by evaporating or condensing the refrigerant.

In 2-pipe VRF systems, all indoor units operate in the same mode – either heating or cooling – at any given time. Three-pipe VRF systems add a third line for hot gas, alongside liquid and vapour lines, and use a refrigerant distribution unit to direct refrigerant where it is needed. This arrangement enables simultaneous heating and cooling in different zones, making it well suited to buildings with varied load profiles.

This CPD on VRF systems in hotel retrofits is supported by Daikin, which pioneered VRF technology and brought it to market as VRV.

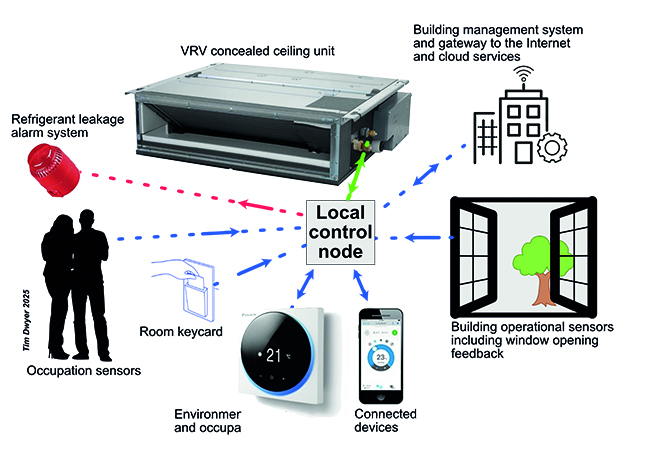

The principal benefits of VRF in hotels include the ability to regulate temperatures in each room individually via local controls, which is valuable given that guests have varying comfort preferences. Systems can be integrated with key-card controls, window contacts and occupancy sensors, so that heating and cooling are reduced or switched off automatically when a room is unoccupied or a window is open.

For a large hotel, multiple VRF systems may be installed, each serving a section of rooms or a zone. In a 150-room example, there may be around a dozen separate VRF systems, each supporting a block of 12 or so rooms.

VRF systems are generally efficient because their variable-speed compressors adjust refrigerant flow to meet demand, improving part-load performance. This is particularly relevant in hotels, which often experience fluctuating occupancy rates and differing load profiles across the building.

Heat recovery VRF systems can move heat extracted from areas requiring cooling to areas that need heating, or use it to preheat domestic hot water (DHW), improving energy use. Additional refinements available from various manufacturers include the ability to vary refrigerant operating conditions, such as temperature and flow, to align more closely with the actual thermal loads in each zone and thereby optimise energy use.

Newer generations of VRF systems are increasingly being supplied with integrated safety and monitoring features. These include built-in refrigerant leak detection to comply with A2L refrigerant safety requirements, and connectivity that allows systems to be linked to cloud platforms for remote diagnostics and predictive maintenance.

Such functionality enables facilities managers to identify issues before they result in downtime, optimise performance through continuous monitoring, and ensure that leak management and compliance obligations are more easily met.

While VRF systems offer notable advantages in efficiency, control and installation flexibility, they also present some limitations. Their performance in heating mode can be temporarily reduced during defrost cycles, which should be considered in sizing and control strategies.

System complexity and the reliance on refrigerant distribution throughout the building can make diagnosis and repair more specialised than with simpler heating or cooling systems, potentially affecting maintenance costs and response times.

Because refrigerant pipework extends into occupied spaces, compliance with safety standards – particularly for mildly flammable refrigerants – is essential. In some cases, especially with older buildings, achieving the necessary pipework routing or meeting refrigerant charge limits can add to project complexity.

Environmental considerations have also influenced VRF system development. Historically, most VRF systems have used R410A refrigerant, a blend of R32 and R125, with a 100-year GWP of 2,088, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report (AR4),5 which is classified as A1 (lower toxicity and non-flammable) under BS ISO 817/ASHRAE 34. Many new systems now use pure R32, which has a significantly lower GWP. (See CIBSE Journal, June 2022, CPD module 198 for more discussion on this.)

In regulatory terms, R-32’s GWP is defined as 675 under the IPCC AR4 methodology. This value is used for F-gas compliance and refrigerant quota calculations in both the UK and EU, and is slightly below the maximum GWP permitted for refrigerants under the UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard (UKNZCBS). Although the IPCC has published updated GWP values in later assessment reports (AR5 and AR6), UK and EU regulations still reference AR4 figures to ensure consistency in legislation, quota management and international trade reporting. In AR6, the GWP is stated as 771.

When replacing existing systems, an alternative to VRF in some retrofit scenarios is a polyvalent heat pump (sometimes referred to as a 4-pipe heat pump chiller) that can provide both heating and cooling, typically using water as the distribution medium.

However, converting from VRF to such a system normally requires replacing all fan coil units (FCUs) and associated pipework, which can be disruptive to operations. While polyvalent systems can reduce the total refrigerant charge in occupied spaces, the financial and embodied-carbon cost of replacing VRF room units and pipework may limit their suitability in some projects.

The decision to replace a VRF system is often influenced by age and condition. With regular maintenance, VRF systems can operate for 15 years or more, but efficiency can decline over time, parts can become difficult to source, and failures can cause rooms to be taken out of service. Replacing older systems with high-efficiency models can therefore yield operational benefits in addition to energy savings.

A recent UK city hotel retrofit, documented in an Arup case study,6 replaced the existing heating and cooling plant with heat recovery VRF systems as part of a wider net zero carbon strategy. The system enables heat extracted from areas requiring cooling to be reused in spaces needing heating, improving efficiency and reducing fossil fuel use.

The project considered pipework routing within the existing structure, refrigerant charge compliance, and integration with the building management system (BMS), achieving better operational energy performance and enhanced comfort without the disruption of a full plantroom rebuild.

R32 systems can offer improved volumetric efficiency over R410A models, typically reducing refrigerant charge by around 10% and increasing seasonal efficiency by more than 10% in some cases, though actual performance depends on system design and application. R32 is classified as mildly flammable (A2L), which means safety provisions such as leak detection, ventilation and system charge limits must be considered in design. (See CIBSE Journal, October 2024, CPD module 237 for more discussion on this.)

The use of refrigerants in VRF systems is subject to the UK’s retained F-gas Regulation, which implements a phasedown in hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) supply. While there is no immediate ban on R410A in existing systems, from 2029 new split systems with a cooling capacity greater than 12kW must contain a refrigerant with a GWP less than 750. In response, most manufacturers are now offering R32 as their main VRF refrigerant.

The so-called ‘product family standard’ BS EN IEC 60335-2-40:20247 includes requirements for leak detection, ventilation and system design by dividing spaces into leak hazard areas to assess the risk if a refrigerant escapes. Area 1 is the high-risk zone immediately around parts of the system – such as an indoor fan coil – where a leak could cause refrigerant levels to exceed the lower flammability limit (LFL).

In these locations, the standard may require additional measures, such as leak detectors, automatic shut-off valves or enhanced ventilation. Units, such as the example in Figure 1, have specific features to meet these requirements.

Figure 1: An example of a VRF room unit with integrated refrigerant leak sensor. Detection of a leak automatically isolates the connected refrigerant circuit and activates a local alarm. The environmental monitoring and control of the unit can be linked to a suitable selection of inputs and outputs – both local and cloud-based

Area 2 covers the remainder of the occupied space, where refrigerant is likely to disperse and remain below the LFL, so fewer safety measures are normally needed. This zoning approach helps designers target protective measures where they are most critical, while avoiding unnecessary interventions elsewhere.

VRF installations must also comply with BS EN 378 – the horizontal refrigerant safety standard – that covers toxicity and flammability risks across all refrigerant classes and system types. By contrast, BS EN IEC 60335-2-40:2024 – as a vertical product-family standard – specifically addresses the safe use of flammable A2L refrigerants, such as R32, in larger systems, introducing detailed provisions on leak hazard areas, ventilation and ignition control.

If a replacement VRF system uses a different refrigerant classification from the original – for example, switching from a non-flammable refrigerant to R32 – it will be necessary to replace both indoor and outdoor units and the existing pipework. (See CIBSE Journal, June 2022, CPD module 198.)

Replacement systems must also meet Ecodesign requirements. Lot 218 of the EU Ecodesign Directive, retained in UK law, sets minimum seasonal performance standards for heating and cooling products. These include seasonal energy efficiency ratio (SEER) for cooling and seasonal coefficient of performance (SCOP) for heating, as measured under EN 14825 part-load and full-load conditions.

In the EU, the development of the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR9) will probably extend the areas that need to be considered beyond those of Lot 21, as outlined in the boxout below.

From Lot 21 to ESPR: what the shift could mean for VRF systems

The EU’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), adopted in 2024, builds on existing Ecodesign rules such as Lot 21, which sets minimum seasonal efficiency standards for comfort cooling and heating products. While Lot 21 focuses mainly on operational performance (SEER and SCOP), ESPR will expand requirements to cover whole life environmental impacts.

Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) are standardised third-party-verified documents quantifying the environmental impacts of a product. CIBSE TM65 is a method for estimating the embodied carbon of building services equipment when full EPD data is not available.

For VRF systems, ESPR could mean mandatory ’product passports’ detailing refrigerant type and charge, leakage rates, repairability, recyclability and expected lifespan. Procurement decisions may increasingly weigh circular economy metrics alongside efficiency data, with possible extended producer responsibility for end-of-life recovery.

Although ESPR is not yet in force in the UK, aligning early could help future-proof designs and avoid non-compliance in export markets. For engineers, it offers an opportunity to integrate operational and embodied performance into HVAC system selection.

In hotel retrofits, DHW production is a major part of energy demand and integrating it efficiently with the VRF plant can improve the overall performance. Options include manufacturer-specific hydro-modules that recover waste heat from the VRF circuit, dedicated air-to-water heat pumps installed in parallel with the VRF system, or electric immersion and boiler systems as backup or supplementary heat sources. In all cases, hot-water storage helps manage peak loads.

Figure 2: A Daikin Round Flow FXFA-A ceiling-mounted air conditioning unit, optimised for R-32 refrigerant

Effective controls are critical in maximising efficiency and comfort in a VRF retrofit. In-room controllers should be simple to operate and use symbols to overcome language barriers. Integration with occupancy sensors, key-card systems and window contacts can enable automated energy-saving adjustments.

Wireless connections between these devices and the controllers can reduce installation complexity. Centralised control systems allow FM staff to manage VRF units from a single platform, often with web-based access. They enable building-wide settings such as temperature setbacks, setpoint limits and mode restrictions to be applied remotely.

Integration with the BMS via Modbus, KNX, HTTP, or BACnet/IP allows the VRF plant to operate as part of the wider building services strategy. Cloud-based platforms can also support multi-site monitoring, energy logging and predictive fault detection.

Hotels generally have higher energy use intensity than many other commercial building types, and guest expectations around comfort remain high. Without ongoing investment in efficiency and decarbonisation, hotels risk operational cost increases, reduced competitiveness and reputational impacts.

Including HVAC upgrades – such as replacing older VRF systems with more efficient, lower-GWP alternatives – as part of planned refurbishment cycles can help to manage these risks and contribute to long-term sustainability goals.

© Tim Dwyer and Andy Pearson, 2025.

1 bit.ly/CJOct25CPD1 – accessed 13 August 2025.

2 bit.ly/CJOct25CPD2 – accessed 13 August 2025.

3 bit.ly/CJOct25CPD3 – accessed 13 August 2025.

4 bit.ly/CJOct25CPD4 – accessed 13 August 2025.

5 IPCC Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007 (AR4) – Physical Science Basis, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

6 Transforming existing hotels to net zero carbon, ARUP, 2022 – available at: bit.ly/CJOct25CPD5.

7 BS EN IEC 60335-2-40:2024 Household and similar electrical appliances – Safety – Particular requirements for electrical heat pumps, air conditioners and dehumidifiers, BSI 2024.

8 EC Reg 2016/2281 (Lot 21) implementing Directive 2009/125/EC with regard to ecodesign requirements for air heating products, cooling products, high-temperature process chillers and fan coil units, EC 2019.

9 Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR). Regulation (EU) 2024/1781, EU Commission 2024 – available at: bit.ly/CJOct25CPD6.