The drive to reduce building-related emissions is leading to an uptake in the use of heat pumps to generate low carbon heat in commercial buildings. Heat pumps are one of the most cost-effective options to reduce carbon emissions from new buildings, when acting as the sole heat generator.

Heat pumps alone, however, may not always be the most appropriate or cost-effective means of providing all the heat for new build and existing buildings undergoing refurbishment or upgrade. A well-established method for building occupiers or owners to transition to a lower-carbon heating solution cost-effectively, and without compromising on comfort, is a hybrid or bivalent solution, where heat pumps are combined with traditional heating systems.

This CPD outlines some of the ways an air source heat pump (ASHP) can be combined with a traditional heating system, and the pros and cons of each option.

LISTEN TO A TWO-MINUTE AI OVERVIEW OF THIS CPD

What is a hybrid system?

A hybrid heat pump system combines two or more heat sources. Typically, this involves pairing an ASHP with a secondary heat source, most commonly a gas-fired boiler, but it can also be an electric or oil-fired boiler, or even a connection to a district heating system.

Hybrid systems can be retrofitted on any scale of building, from domestic to industrial, where they are often implemented as an intermediate or transitional stage from an all-fossil to an all-renewable heating solution. Drivers for hybrid systems include reducing capital expenditure in meeting high peak heat demands and resilience.

In a hybrid heating system, the heat pump typically handles the majority of the building’s heating demand, with a secondary heat source stepping in only when needed. This secondary source may activate for a variety of project-specific reasons. For example, to avoid the capital expenditure of sizing the heat pump for peak demand, or to minimise the use of electricity at peak tariff. In ‘cold weather assistance’ mode, it switches to the secondary heat source when outdoor temperatures fall below a set threshold.

The secondary source can also serve as a ‘backup’ if the heat pump is out of action, or meet extra demand during periods of unusually high heating requirements – such as in buildings with variable occupancy. This approach allows the ASHP to be sized smaller, since the boiler can provide additional heating on the coldest days.

In some less common configurations, the heat pump is dedicated to space heating while the boiler continues to supply domestic hot water (DHW), separating the two functions entirely.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution – the system should to be configured for each project and budget.

The design of hybrid systems

In a hybrid system, it is important to manage how the heat pump and boiler interact with the rest of the heating system. Ideally, these two heat sources should be hydronically decoupled. This means that they should not share the same circulation loop but should still be thermally connected so that both can contribute heat effectively.

One common way to achieve this is by using a buffer tank to decouple the heat pump. The buffer acts as a thermal store, allowing the heat pump to operate in longer, more efficient cycles while helping to smooth out fluctuations in heating demand.

The boiler is typically connected via a low-loss header, which is usually a short, large-diameter pipe. This hydraulically separates the boiler circuit from the rest of the system. It allows water to circulate freely within each loop without creating unwanted flow or pressure imbalances. It ensures the boiler can add heat to the system when needed, without interfering with the operation of the heat pump or the buffer tank.

Together, the buffer tank and low-loss header enable the system to be balanced and controlled. The heat pump can efficiently meet the base heating load, while the boiler can step in to cover peak demand or provide backup.

In some hybrid systems, particularly where full hydraulic separation is required, plate heat exchangers may be used to transfer heat between the heat pump circuit and the main heating system. These allow thermal energy to pass from one loop to another without mixing the water, which can be especially useful when the heat pump operates on a different pressure or fluid quality regime than the rest of the system. Heat exchangers can also provide an added level of protection by isolating sensitive equipment from legacy systems that may contain older pipework or have water treatment issues.

The main hybrid system configurations

Ultimately, selecting the most appropriate hybrid heating system configuration depends on the specific needs and constraints of the project. These may include budget limitations, carbon re-duction targets, system compatibility, and the acceptable balance between upfront capital costs and ongoing operational expenses.

A key concept in the design and operation of hybrid systems is the bivalent point. There are two main ways to define the bivalent point. The first is based on heat demand and system capacity. As outdoor temperatures fall, the heat loss from the building increases. If the heat pump has been deliberately sized slightly below peak demand – which is common to reduce capital cost – there will be an ambient temperature threshold at which supplementary heating is required.

The second approach is based on system operating parameters, particularly in weather-compensated systems. In these systems, the flow temperature of the heating circuit increases as the external temperature drops. Eventually, the required flow temperature may exceed the maximum temperature that the heat pump can deliver. At this point, the system switches to or adds the secondary heat source. This temperature is also considered the bivalent point.

Hybrid systems can be broadly grouped into two categories. The first category includes mono-energetic and parallel modes. These configurations are suitable where the flow temperatures remain within the operating range of the heat pump, even down to the design external temperature.

The pros and cons of the four main configurations for hybrid systems:

Mono-energetic mode

Pros:

- Not oversizing the heat pump for rare peak demands can save on costs while still aiming for a high proportion of renewable energy use.

- It can be a step towards decarbonisation.

Cons:

- Still requires electrical infrastructure to support both heat pump and electric top-up

Parallel mode

Pros:

- Maximises the heat pump’s contribution to the total load and, consequently, it can significantly reduce carbon emissions compared with standalone fossil fuel systems.

- Offers flexibility and scalability, as both generators can run together with the boiler assisting the ASHP.

- Addresses situations where there might not be enough space for a full heat pump system or where there are electrical constraints, since the gas top-up will not require more electrical power.

- Cons:

- Often requires changes or upgrades to existing emitters within the building, which can incur higher costs and disruption.

- Requires careful design to prevent the different heat sources from ‘fighting’ each other, which can lead to reduced system efficiency.

- The primary flow temperature and differentials must be suitable for both technologies.2

Switch mode

Pros:

- Allows for heat pumps to be integrated into buildings with legacy heating systems that require high temperatures without needing to change existing emitters.

- Often preferred by private investors focused on running costs, as the boiler will operate when heat pump efficiency drops significantly, usually as the consequence of high system temperature requirements from low ambient temperatures.

Cons:

- The heat pump ceases to operate entirely when temperatures fall below the bivalent point, meaning less contribution from the renewable source compared with partially parallel mode (see below).

- The boiler will cover a larger portion of the annual energy demand and will need to be sized for the full peak heating load.

Partially parallel mode

Pros:

- Maximises the input from the heat pump resulting in greater CO2 emission reductions. As a consequence, this mode is often preferred by local authorities or clients whose main driver is to reduce CO2 emissions.

- Allows heat pumps to operate for longer periods at lower external temperatures while still contributing to high flow temperature systems.

Cons

- Can lead to higher running costs if electricity prices are significantly higher than those of gas, as the heat pump operates more frequently under conditions where its efficiency might be lower (though still better than the boiler).

- Requires a boiler sized for the full peak load.

Mono-energetic mode

This configuration applies to one type of hybrid, where boilers supply additional temperature or capacity (typically 45-60oC, but can be up to 85oC). However, the heat pump is slightly undersized, and an additional heat source is activated at or below the bivalent point (the point where the heat pump alone cannot meet demand). This secondary source can use the same form of energy as the heat pump (for example, an electric boiler with an electric heat pump). The heat pump is often undersized because the period when the additional source is needed might only be 4-5% of the year, making the capital expense of a larger heat pump unjustified.

Parallel mode

In this setup, the heat pump is slightly undersized, similar to the mono-energetic system. In the parallel configuration, as with all hybrid systems, the system is designed so that the heat pump can operate for a much of the year as possible. This may require upgrades to the heat emitters to allow for lower flow temperatures.

The system requires the emitters (for example, radiators) to be compatible with the lower flow and return temperatures delivered by the heat pump. This implies that emitters may have to be changed or upgraded to suit the operation of the heat pump. The secondary heat source provides the remainder of the peak load, limiting its contribution. For example, a 200kW building might have a 150kW heat pump and a 50kW boiler

Building Regulations

Where a heating system has been fully replaced, both mono-energetic and parallel systems will have to meet the maximum flow temperature requirements stated in Part L of the Building Regulations.1

Paragraph 5.10 of the 2021 Approved Document states that where a wet heating system is either newly installed or fully replaced in an existing building, including the heating appliance, emitters and associated pipework then:

‘All parts of the system, including pipework and emitters, should be sized to allow the space heating system to operate effectively, and in a manner that meets the heating needs of the building, at a maximum flow temperature of 55oC or lower. To maximise the efficiency of these systems, it would be preferable to design to a lower flow temperature than 55°C.’

Where it is not feasible to install a space heating system that can operate at this temperature (for example, where there is insufficient space for larger radiators), then the document says the space heating system ‘should be designed to the lowest design temperature possible that will still meet the heating needs of the building’.

The second category of hybrid systems includes switch mode and partially parallel mode. These are typically used in legacy systems where the existing emitters have not been changed, and higher flow temperatures are required during colder weather. In such systems, the heat pump may operate only part of the time, with the boiler taking over when demand exceeds what the heat pump can efficiently supply.

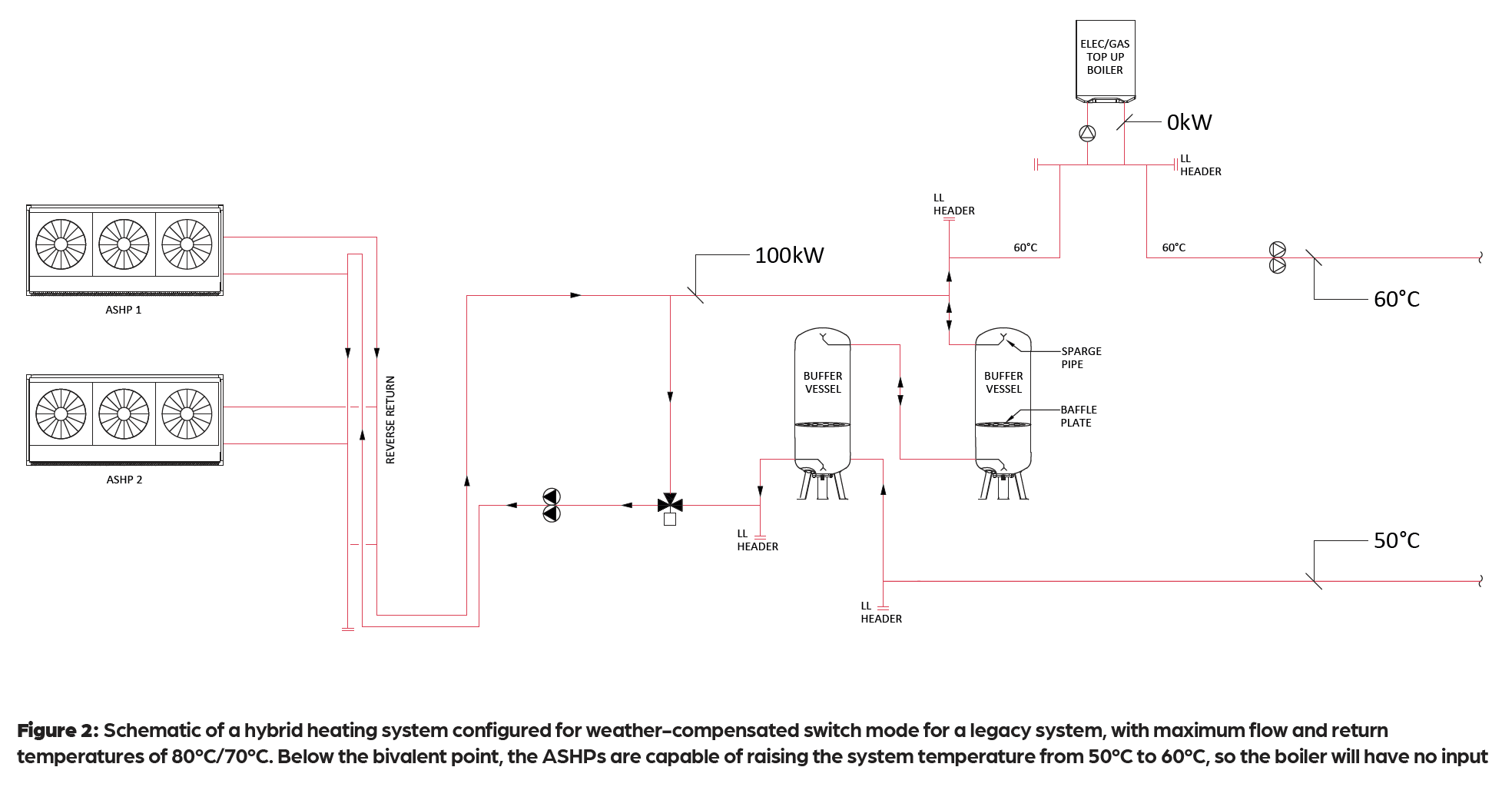

Switch mode

This mode is applicable for legacy systems requiring higher flow temperatures than heat pumps alone cannot consistently deliver – for example, where existing heat emitters are retained. When the external temperature reaches a predefined bivalent point, the heat pump is stopped and the secondary heat source (for example, a boiler) takes over the entire heat load. The switch point is determined by the flow temperature and building load (see Figure 2).

Partially parallel mode

This mode is also used for legacy systems retaining existing emitters and requiring higher flow temperatures. This mode aims to maximise the heat pump’s contribution. Instead of stopping the heat pump at the bivalent point, the system monitors return temperatures. If the return temperatures are still within the heat pump’s operational envelope, the heat pump is used to preheat the system and the secondary source (boiler) then provides the additional boost to reach the required higher flow temperature. This allows both sources to work in parallel for a segment of the load curve.

The importance of controls logic

Hybrid heating systems can be set up to switch automatically between the two heat sources based on certain triggers – for instance, energy tariff or ambient temperature. The controls logic needs to be right to ensure the most appropriate heat source is selected and to prevent the heat generation methods fighting against each other, often at the expense of the high temperature source taking over and impacting system efficiency.

The key to avoiding this conflict and to optimise the performance of the system is to ensure plant is sized appropriately, the controls are properly considered and the hydronic design is correct from the outset.

© Andy Pearson, 2025.

References:

1 Approved Document L of the Building Regulations – bit.ly/CJSep25CPD21.

2 CIBSE Journal, November 2022, CPD module 205, ‘Bivalent heat pump systems for heating and hot water’ – bit.ly/CJSep25CPD22.