It is expected that by 2020 there will be 75bn devices linked to the internet1 – all potentially open to access by malicious users. In the building world, this ranges from wireless temperature sensors, controllers and the myriad controlled components and objects in a building, through to the materials and spare parts wirelessly connecting as they pass through the supply chain, or feeding back their condition to maintain a truly useful building information model (BIM).

This has a significant impact on building services engineering for safety, security and building performance, and is driving building control systems so that they use internet protocol (IP) networks that would have traditionally been used solely for carrying computer network data – such as email, worldwide web access and documents – to and from centralised computer storage (servers). This CPD will look at some of the basic considerations that a building services professional will need to undertake when planning such a networked control system, to ensure a robust and secure structure.

An IP-based network can carry multiple types of building control networks in one cable. This can save costs, be easier to deploy, and be easier to manage over the lifetime of the system. For many building services professionals, moving into the world of IP can be confusing, and it is now common for a client’s IT team to be part of the project design and delivery process. Inappropriate decisions – or poorly installed or maintained services – can quickly cause harm, damage an organisation’s reputation, cause costly disruption and expose the broader networked systems to security (or ‘cyber’) threats from malicious users, from inside and outside the organisation. So, the underlying control networks and their management are crucial for long-term security and success.

Robust network foundations

The foundation of any such control systems – the IP network – needs to be strong, resilient and secure. The heart of any network is the hardware that controls the data traffic as it passes across the ethernet2 networks using ‘twisted pair’ cabling and fibre optic links. These industrial (electronic) switches will fall into one of two categories – managed or unmanaged. Both types of switch allow devices (such as temperature sensors and zone controllers) to communicate with each other. Managed switches provide the ability to configure, manage and monitor the network; unmanaged switches simply pass the traffic through so that it reaches the correct network sections.

Managed switches use protocols such as the simple network management protocol (SNMP)3, which enables and controls the exchange of information from devices on the network. The health – that is, the integrity of connections, and the strength and robustness of signals – and the resulting status of the network can be monitored with SNMP. Alarms – similar to building control alarms – can be triggered by specific events, such as the disconnection of a HVAC controller or broken link to a sensor. Building control system manufacturers are already integrating this protocol into their software to generate and receive alarms. Managed switches can automatically build resilience in the network, and can re-route traffic if a problem occurs, keeping the network working.

Best practice in the creation of networks encourages the segmentation of the network into logically grouped devices. This isolates traffic between these groups, even when the traffic is passing through the same physical switch. This segmentation and isolation of network traffic helps to reduce unnecessary communications by effectively allowing grouped devices to talk to each other locally without passing through the wider network. The simple capital cost of an unmanaged switch will be cheaper than a managed switch, but unmanaged switches aren’t configurable. This means that there is no resilience, no monitoring and no possibility of alarms in the network. The inability to segment the network can also slow down the phased development of a project.

Segmentation can help to isolate and identify network problems. With no SNMP, often the only way to identify the problem is through extensive trial and error. It will enable some ‘intelligence’, so – in the event of a device not being available on the network (such as an AHU) – the SNMP will be able to determine whether the issue is with the physical aspects of the AHU operation or with the network connections.

Converging networks and useful redundancy

Traditionally, building control systems have employed their own separate networks using dedicated wiring or other signal-carrying media. Each network increases the number of points of failure – although some may argue that the separation provides some increase in resilience in case of failure. The additional infrastructure requires more distribution space and, in the case of digital networks, multiple instances of electronic hardware.

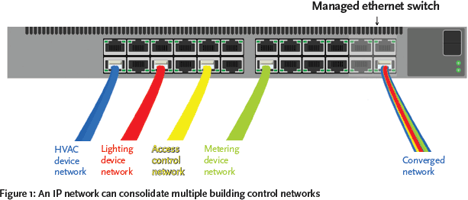

By employing a single managed IP network, these separate systems can be brought together into one (Figure 1). The network can be automatically segmented so that they do not interfere with each other – for example, Modbus4 traffic would not interfere with that of BACnet5, although they would be coexisting in the same network cabling. With fewer networks, deployment is likely to be easier and faster, and the number of single points of failure reduced.

Figure 1: An IP network can consolidate multiple building control networks

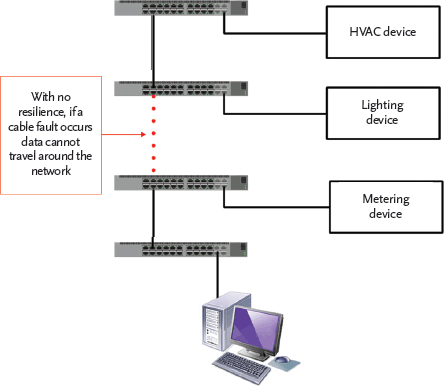

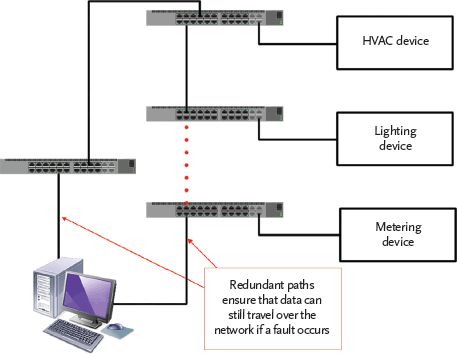

However, converging networks into one can increase risks. If that one IP network fails, as in Figure 2, the building control network traffic fails too. To mitigate this risk, redundancy may be included in the network design and, contrary to their name, redundant network paths are useful. These are additional physical connections that are employed if the primary path fails, as shown (in a simplified example) in Figure 3. Should a failure occur, the managed switch will automatically re-route data. Building redundancy into network designs can remove single points of failure from the network.

Figure 2: A network with no resilience in the event of network failure

Figure 3: A network with some resilience in the event of network failure

Operational practices to improve control network robustness

As with any specialist field, there are numerous opportunities to improve the reliability of provision. Here are some fundamental operational practices that will work together to deliver more robust operation.

Properly managed user accounts – Typically, each control system will have its own personal computer (PC), and it has often been observed6 that contractors will provide a single logon account for that PC – usually the PC’s administration account. This will be shared among the client’s users and the contractor’s maintenance team, and so will provide an uncertain level of security. With a shared logon, it is very difficult to ascertain who has made changes to a system. If that single logon also has the PC’s administration rights, the problem may be exacerbated, because all users will be able to delete or change sensitive files. This is not a secure way to give multiple users access to a system, and it is likely7 that when a user accesses a computer with their personal logon account, they are more responsible for the actions they take on that computer.

Server-based control systems – Many control systems are designed to continuously monitor devices. A ‘server’-based system – using a specialised computer (often away from the workspace or, potentially, in the internet ‘cloud’) – is designed for continuous use, thus allowing the control system to function without interruption. A server utilises that concept of user accountability. Logon accounts can be ‘permissions’-based, with individual users given prescribed levels of access to the system to protect sensitive applications and data. Serverbased systems are likely to employ more robust security, with the need for stronger passwords and the requirement to alter passwords at regular intervals.

Specifying a server environment for a project eliminates the need for multiple stand-alone PCs. Through a process called virtualisation, a server hosts many virtual PCs. These individual PCs are known as virtual machines (VMs)8 and, for users accessing these from, for example, a simple remote terminal, a tablet computer, or touch screen, it simply appears that they are using a ‘normal’ computer. Hosting VMs in a server environment makes it easier to back up and restore control systems and databases, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: In a virtualised environment, if one server fails, the second can automatically take over the work, so that the BMS and control systems will still operate

Data can be lost to cyber threats or simple human error, and the data loss may cause more problems than the original threat. Building control systems tend to collect data over a long period of time, and the data requires regular backing up and archiving. Using specialist software, all of the separate building control systems hosted on the server can be mirrored (replicated) on to a second server. If a failure occurs in the primary server, the secondary server will take over. Backups can be taken at regular intervals and saved offsite on to other media – such as tape drives and archive discs – and modern backup software allows the restoration of ‘lost’ data within minutes.

Secure remote access – The ability to remotely access a building control system, using an internet connection, can help to reduce the number of site visits, and provide speedier service response times.

In recent months, there have been several well-publicised instances of illicit remote access to building control systems. Practically – and currently – it is not difficult to find unsecured remote access networks available from the web. These typically demonstrate three areas of lapse security management:

- The building management system (BMS) is

readily visible from the web - Access is authorised from the web to the

BMS, regardless of which computer is trying

to access it - There is no username or password required

to access the BMS

These can be fixed with the right procedures and management, to ensure the remote access is relatively secure. With an appropriate ‘firewall’ – software that filters the packets of software that can pass into the control network – a secure private network can be made to a specific computer, or another network. This would reject access to the BMS from anywhere else, and allow the management of access rights to specific sections of the control systems.

Additionally, using secure socket layers (SSL) technology ensures that the remote access session is authorised and encrypted over the web. Some SSL servers can identify that the user is accessing the system with the right operating system and up-to-date anti-virus software.

Private networks in place of the internet

Hacking will always be there if the internet is used to provide remote access. However, using a ‘private’ network can allow a more secure option. There are many ways to achieve this. Two low-cost and flexible methods that can be considered are:

Digital subscriber line – DSL9 access into a private network provides high-speed network access points, although not necessarily connected to the internet. It can be used to create a very secure network direct to the control system. It benefits from the same high speeds as commonly used broadband (DSL) and, in the UK, costs the same, at around £40 per month.

3G/4G wireless access10 – Mobile telephone access is becoming widely available to provide high-speed data over a mobile providers’ network. Like DSL, 3G and 4G services can avoid the internet altogether. Using special machine-to-machine (M2M)11 electronic access cards, these services can connect to a specific private network. The typical UK cost of these services is about £20 per month.

Private network services are particularly useful during the defects liability period of projects, where they can provide secure and measurable access to systems to monitor and amend control system configurations, while helping to reduce the number of required site visits. Once the liability period is over, the connection equipment could be moved to another project.

The building services industry will inevitably employ increasing numbers of IP networks for building control systems, opening up to a different realm with its pre-existing standards and knowledge – as well as exposing itself to ‘cyber’ threats and other, non-malicious, issues.

Cyber threats will target those with the lowest levels of security, so building security into projects can protect systems and the reputation of end-users and professionals. But protection is only part of the solution. Resilient networks can help to ensure BMS continue to operate, protecting client data and restoring control systems.

Since the movement of the technology into building services applications is relatively new, an appreciation of best practice in securing building control systems can help to differentiate the potential capabilities of designers and contractors.

© Tim Dwyer and Chris Topham, 2014.

Further reading

Chapter 4 of CIBSE Guide H (2009), Controls provides an excellent introduction to ‘Systems, networks and integration’, although some areas will have developed in the five years since publication

The UK government’s Office of Cyber Security and Information Assurance promotes online safety through such initiatives as www.getsafeonline.org/businesses

The USA has set up a cyber security division under Homeland Security – see www.dhs.gov/topic/cybersecurity for some of their practical tips.

References

- www.businessinsider.com/75-billion-devices-will-be-connected-to-the-internet-by-2020-2013-10

- http://computer.howstuffworks.com/ethernet.htm

- www.snmplink.org/

- www.modbus.org/faq.php

- www.bacnet.org/

- Private communication with field staff from Abtec.

- http://pic.dhe.ibm.com/infocenter/zos/v1r12/index.jsp?topic=%2Fcom.ibm.zos.r12.icha700%2Fichza7b012.htm

- http://searchservervirtualization.techtarget.com/definition/virtual-machine

- http://whatis.techtarget.com/reference/Fast-Guide-to-DSL-Digital-Subscriber-Lin

- http://consumers.ofcom.org.uk/what-is-4g/

- http://gcn.com/articles/2013/03/22/m2m-future-ofcode.aspx