The wadi in flood, with terraces and villages above terrace plantations on the right bank, and densely populated, mixed-use buildings on the left.

The client’s competition brief for a new city in the Middle East sounded more like an academic exercise than the requirements for a real masterplan.

‘Create a city for 280,000 people that uses half the normal amount of energy and water, yet doubles available floor space and costs less than business as usual. Oh, and halve the number of cars as well.’ This wasn’t an exercise for students, however; these were the key performance indicators for a major new conurbation in Oman.

Madinat Al Irfan is a city extension for Muscat, which will have more than 2,000 buildings, 14 mosques and 17 schools. It is positioned between the Gulf of Oman to the north and the Al Hajar mountains to the south, and will be unlike any other modern city in the region. Rather than featuring towering glass-and-steel skyscrapers connected by eight-lane highways, it will be a low-rise, densely populated city built on traditional Middle Eastern principles of architecture – narrow streets, lots of shading, and low water use. The steep-sided valley – known as a wadi in Oman – running through the site won’t be built on, but will be enhanced to create an identity for Irfan based on its local climate and heritage.

Irfan is designed to be a post-petroleum city, where people can walk to shops, schools and places of work, rather than rely on cars. The long-term goal is for a new Oman light rail transit to stop in Irfan, further reducing the need to drive. In the context of the high-rise cities typical of the Middle East today, the aspiration sounds fanciful. But if governments are to reduce carbon emissions by up to 70% by 2050 – and achieve net zero emissions by 2100 – then cities like Irfan will have to be the norm.

The client brief

Specialist built-environment adviser Chris Twinn FCIBSE devised the masterplan brief with the client, the Oman Tourism Development Company. His years of experience working on low-carbon developments in China and the Middle East led to RIBA recommending him for the job.

If sustainability is considered at the start of a project, it should incur less – not more – cost than ‘business as usual’ (BAU), says Twinn. ‘Attention, at the earliest stage, to building form, microclimate and transport infrastructure can vastly reduce energy loads,’ he adds.

‘My argument is it should cost less because you’re using less stuff [HVAC equipment]. That’s why sustainability targets were in the brief – it reduced costs. I’ve managed to get fairly advanced levels of sustainability into other projects because sustainability is less than BAU. We are entering a cost-constrained world – there aren’t that many rich benefactors around.’

Section view of block showing the extra lettable space created when façade overhangs are incorporated. Basement car parking is reduced from four to two levels

Twinn says engineers must be aware of the financial cost of their designs to stand a chance of influencing designs. ‘As an engineer, I learned that if you wanted more than three conduits, it was cheaper to go for 50mm x 50mm trunking,’ says Twinn, who believes – in the UK – quantity surveyors (QSs) have taken away responsibility for costs from engineers. ‘In most other countries, services engineering is not a separate discipline of QSing,’ he adds.

The client helped Twinn achieve the sustainability KPIs for Irfan because it wasn’t interested in the ‘highest, tallest, or biggest’, but wanted a cost-conscious, energy-efficient design in a world with ever-scarcer resources.

‘You have to communicate these ideas in non-engineering terms,’ Twinn says. ‘We discussed the cultural background of buildings in Oman, where streets are high-density, narrow and self-shading, and where you keep the sun off the glass.’ That was much more easily understood than calculations about solar gain, he adds.

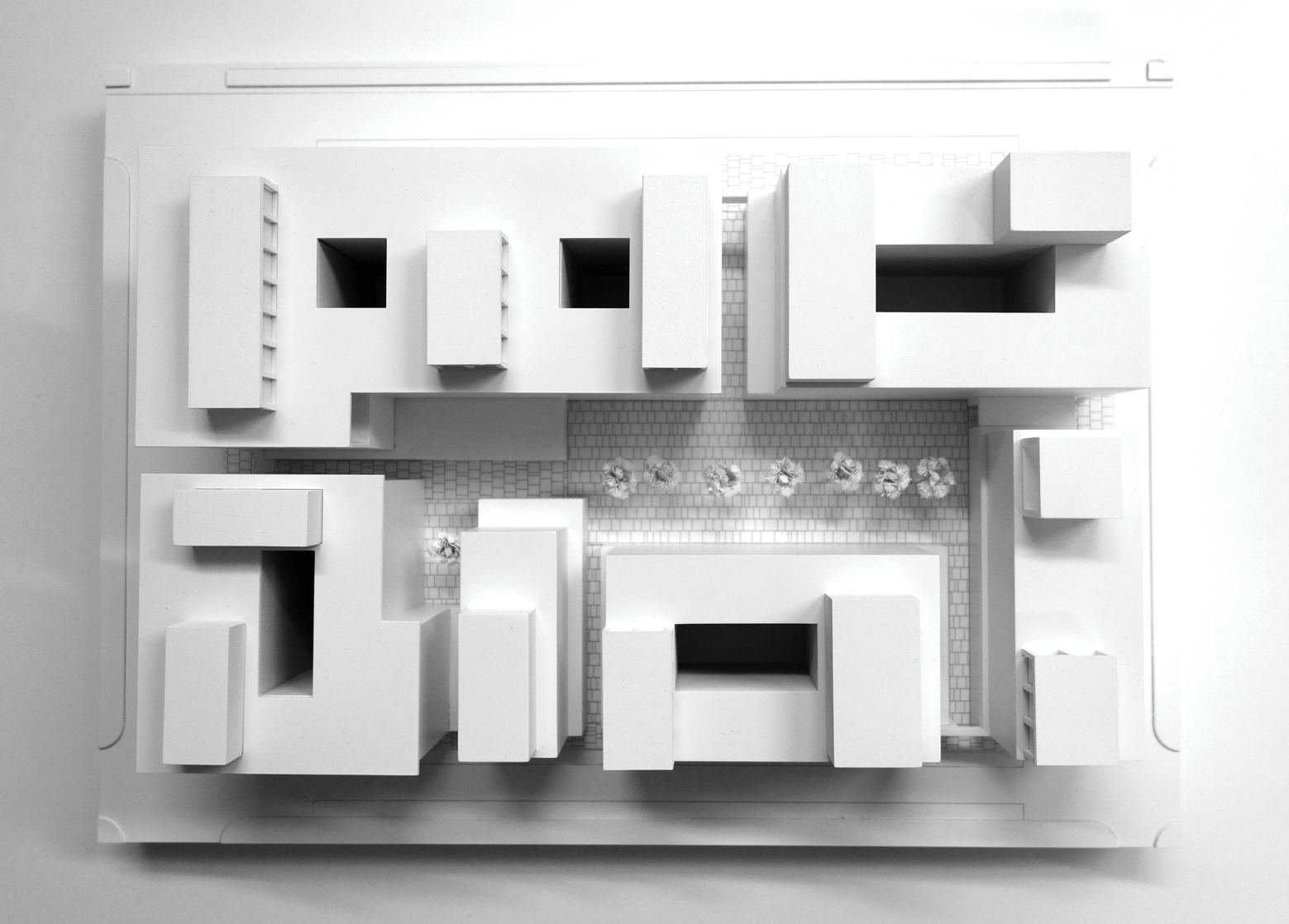

Model of a block showing wind and pedestrian pathways between the buildings

It’s also vital to consider the physics and passive measures in the brief, says Twinn. ‘As an engineer, you have to explain the principles of what you want to achieve before the architect starts the design. As soon as they put pen to paper, they are on the defensive.’

To alert designers to the benefit of thermal mass in reducing energy loads, it needs to be quantified before models are built, because ‘models don’t tell you what thermal mass is doing,’ says Twinn, who successfully worked with Hopkins Architects to use thermal mass to control the environment at the Inland Revenue Centre in Nottingham.

As well as the four KPIs – less water and energy use, fewer cars, and more available floor space – the masterplan competition brief contained 11 guiding principles to encourage the design of a walkable, low-carbon city. (See panel, ‘Guiding principles’).

Guiding principles

- Learn from the past to inform the future

- Create places of distinct character

- Create a comfortable environment for pedestrians

- Provide an integrated transport system

- Create active, mixed-use places

- Create an integrated, sustainable community

- Celebrate the natural landscape

- Embrace quality and diversity in buildings

- Complete at every stage

- Smart-city concept

- Provide a catalyst for change

The winning masterplanning team added five more principles, including making the most of the site’s strategic location close to the international airport and between the sea and the mountains. The team wanted to design villages that were sympathetic to the wadi (deep valley) that runs through the site, and came up with the term ‘string of pearls’ to describe how a cluster of developments with their own character would be built along the wadi.

The winning masterplan

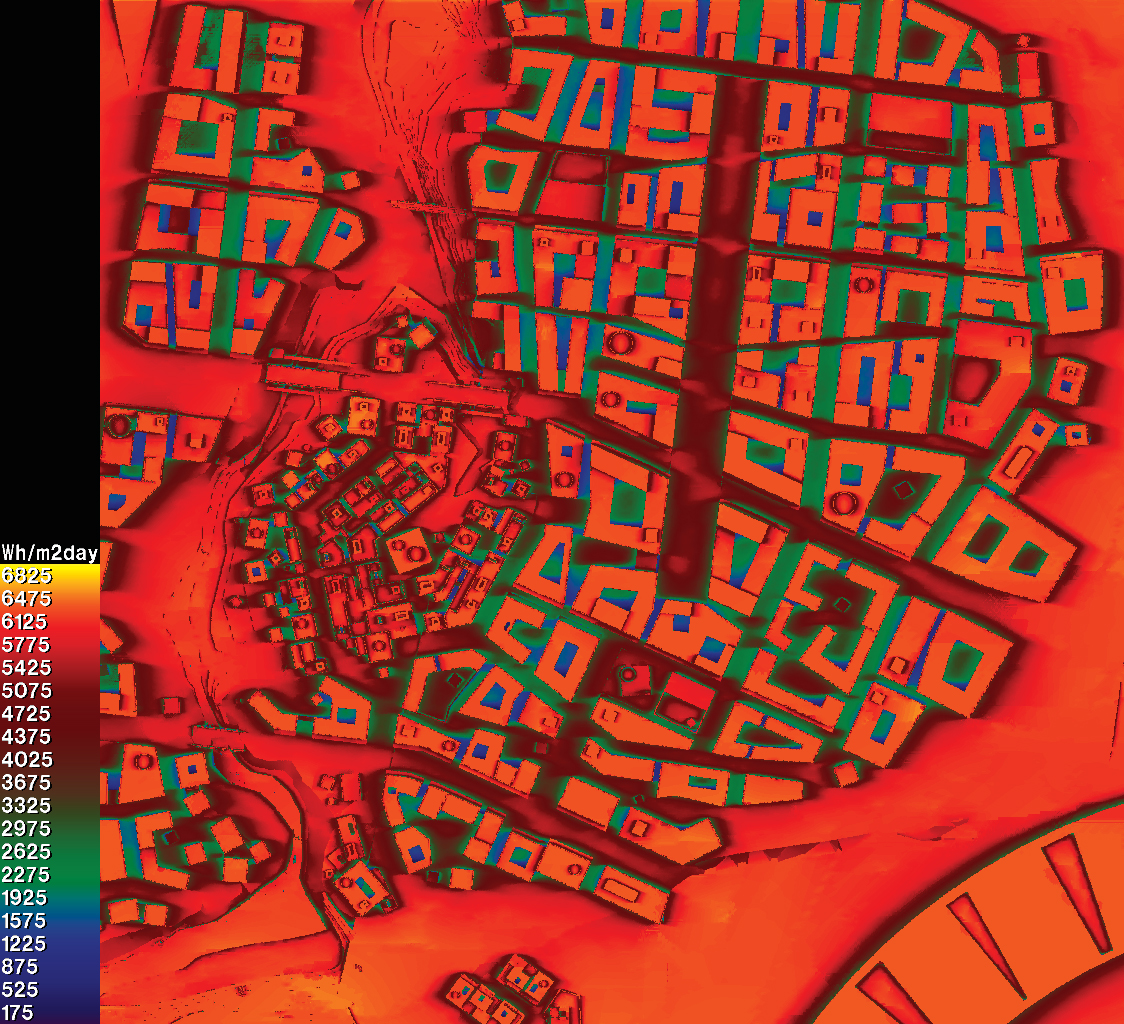

Solar modelling helped to determine street orientation. Narrower streets are east to west

Twinn helped judge the competition entries with design-review panel Cabe and – in a blind assessment – they chose the submission of UK consultants Arup and Allies and Morrison. The judges were impressed by how closely they followed the brief for a site-sensitive design, and not imposed a western style of architecture. ‘Some entries featured big avenues and significant areas of grass, and were very orthogonal,’ says Twinn.

The winning masterplan has a cluster of villages along the wadi, linked by 15 new bridges to more mixed-use areas on a plateau. It stuck to the principles of high-density design with narrow streets and self-shading buildings, featuring airtight, insulated properties with limited glass. The wadi will become a natural park, featuring a steep-sided bank on one side and terraces of traditional plantations – such as figs – on the other. (See panel, ‘Halving water use’).

Density

To inform the design of a ‘walkable city’ in the Middle East, the masterplanning team did extensive modelling of the microclimate to ascertain the optimum orientation, size and height of buildings. Blocks featuring jetties and colonnades were modelled to give a thermodynamic comfort rating for streets, says Arup site development engineer Richard Totten. ‘We did studies on how long you can walk without shade at different times of the day,’ he says. ‘The analysis concluded that 80-100m was the maximum comfortable walking distance when in the sun.’

A requirement of all entries in the client’s brief was to state the amount of 100% shaded walkway that would be provided per square kilometre of masterplan. The idea was to encourage a far denser building form.

Shading doesn’t just encourage walking, it also helps lower the cooling loads in buildings – and the colonnades offer an opportunity to increase lettable floor area. ‘You can build over them,’ Twinn says.

The masterplan showing the more sparsely populated villages to the south of the wadi, and the dense, mixed-use clusters to the north

‘It’s the opposite to what you would do in Britain,’ says Allies and Morrison’s associate director Peter Ohnrich. ‘Here, you want to open up [the street] to get the sun in, but – at Irfan – you have a wide street corridor at the base, but you reduce the opening higher up [to create shading].’ Areas of high density also save energy in the infrastructure, adds Totten.‘We’re not distributing power and water over such large areas. We have concentrated loads, so losses are reduced. It means district cooling is a possibility,’ he says.

A more walkable city with narrower streets means fewer vehicles. Surface car parking is banned and only two storeys of parking beneath buildings is permissable, leading to significant cost savings.

Design codes

The masterplan offers architects and developers flexibility over the choice of materials and styles, but strict parameters must be adhered to. ‘We made early estimates about what we could achieve through passive design,’ says Totten. ‘It was a key focus.’

As a result, design codes stipulate that window-to-wall ratios must be no more than 20% – to reduce overheating – unless there is some form of mitigation against the resulting solar gain, such as shading, deep window reveals or solar-control glazing with low G-values. There is also a target for each block to generate 20% of energy from onsite renewables – primarily a combination of solar hot water and solar photovoltaics.

Thermal studies were carried out on blocks of buildings to determine their most efficient size and orientation. In the design guide, there are several block sizes to reflect different areas. For example, the souks – Arab marketplaces – have smaller, lower-rise buildings to reflect their historic character.

Façade overhangs will be prominent on east-west streets

High-level and projecting cornices, used to shade streets and façades

Canopies and fins, incorporated into façades to shade windows

Wind and solar analyses were conducted on typical development blocks, to ensure there was enough shading and cross-wind to cool courtyards and buildings. For each block, whether residential or commercial, the developer will be given the appropriate design codes. ‘The essence was to make the codes as user-friendly as possible. We put everything on two sides of a piece of paper,’ says Ohnrich.

This contains references to codes applicable to each particular block, such as cornices and colonnades. They are not fully prescriptive says Ohnrich. ‘As long as they comply, the design doesn’t have to match the next block,’ he adds. ‘The relationship will be coherent, but there is variation.’

Carbon and capital cost

Arup and Allies and Morrison calculated the capital and carbon costs of Irfan. The capital cost was slightly cheaper than business as usual (BAU), but the operating and user costs were significantly less – around half BAU. Water costs are 40% less, because of the reuse of water from the treatment plant and other water-saving initiatives, such as native plants, water-efficient fixtures and fittings, and district cooling.

The carbon cost of capital was approximately the same as BAU – this included construction of a light railway transit, which had a high carbon

cost. There were carbon savings because less equipment was needed for cooling, but carbon costs were higher for glazing and extra thermal mass

(it is expected most of the city will be built with traditional stone).

In operation and use, there is a drop of 42% in carbon cost. As operating/user costs are normally around 15 times higher than capital carbon costs, there is huge potential significantly to reduce carbon over time.

Energy infrastructure

Metering is an important part of the design requirements of Madinat Al Irfan, and the aim is, eventually, for live operational data to be used by utilities firms to manage demand.

The data will also be used to ensure future infrastructure development is sized correctly ‘Sizing for peak demands is difficult and it is the utility providers’ prerogative to reject developments if they think the infrastructure is insufficient,’ says Ohnrich. ‘In the first phase, there may be larger pipes, but it’s embedded that – once data is available – developers use it to justify using smaller pipes in future.’

To give reassurance to utility companies, the masterplan has plots notionally dedicated to substations and space within utility corridors for large installations. ‘It’s difficult to know what the instantaneous peaks will be during, say, the Qatar World Cup,’ says Ohnrich, who adds that plots assigned to extra substations could be redeveloped once peaks are known.

Having water use

A key requirement in the client’s brief was to cut water use by half. Annual average rainfall for Oman’s capital, Muscat, is only 100mm (compared with 584mm in London), so it was important for the masterplanners to consider how they could conserve every drop of water.

The visualisation on page 27 shows a flooded wadi, but – for the majority of the year – there is only a small water course. Average temperatures of 35°C in Muscat mean water features are kept to a minimum, because large expanses would evaporate. The only pools of water in the landscape are in areas shaded by bridges.

A narrow falaj waterway in Oman

Narrow, deep waterways, designed to limit evaporation, are used to water the plantation terraces; these are inspired by the design of a 2,000-year-old Omani irrigation channel, known as falaj.

Arup site development engineer Richard Totten says they were fortunate to have an existing waste-treatment facility on site, as it meant there was a source of non-potable water that could be used for flushing, irrigation and some of the few water features. ‘It means there will be water in the wadi throughout the year,’ he adds.

Part of the water treatment will be carried out naturally when it irrigates the plantation terraces. ‘We use solar pumps to irrigate the landscape, and the nutrients are absorbed by plants and fractured limestone in the area. Pumps bring the water back to the surface, and you have a very clear body of water.’

Sites will be encouraged to remove waste water safely onsite, rather than relying on big surface pipes and pump stations – ‘unless they can prove it’s impossible, then they can tap into the city infrastructure,’ says Totten.

Governance

Public spaces will be designed as places for people to meet

To ensure the design codes are followed, there will be a system of verification and a proposed governance structure and planning process.

The masterplanning team, says Irfan, will be a blueprint for future developments in the Middle East and beyond. Energy has been subsidised in the resource-rich region, so energy efficiency has lost importance, says Totten. ‘By building correctly, the government can eradicate subsidies on energy and water, and still not increase people’s bills.’

Key to the savings is the return of traditional building styles, says Totten. ‘We are not imposing something on Oman. We’re reminding them why buildings were like this originally. Our calculations backed up the historic designs.’