Biophilic design, the practice of embedding nature and natural references within the built environment, has long been associated with improved wellbeing. Research suggests contact with nature reduces stress, restores mental focus, and provides a sense of refuge and safety.

A recent paper1 by Dr Yangang Xing FCIBSE and colleagues at Nottingham Trent University extends this evidence base with an empirical study that examines the three established biophilic theories, and introduces a fourth – that biophilic environments may also stimulate inspiration. The findings offer quantitative insight into how varying degrees of biophilic quality influence psychological states.

The concept of biophilia, meaning ‘love of life’, was first articulated by Erich Fromm in the 1960s and developed by Edward O Wilson in the 1980s, with further theoretical grounding provided by Wilson and Stephen Kellert in the early 1990s.

In modern urban societies that keep people indoors for most of the day, connection with nature is increasingly fragile. Surveys regularly reveal dissatisfaction with workplaces lacking greenery, daylight, colour or art, features linked to positive affect and productivity. Such environments may erode wellbeing and contribute to complaints, collectively known as ‘sick-building syndrome’.

Three psychological theories are commonly referenced. Stress-recovery theory suggests that exposure to nature lowers arousal; attention-restoration theory proposes that natural settings replenish directed attention; and refuge and prospect theory holds that environments offering protection and outward views satisfy deep-rooted preferences for safety. Xing and his colleagues tested all three and added the biophilic-inspiration hypothesis, proposing that natural surroundings may evoke motivational and creative states.

The researchers recruited 255 participants, aged 18 to 77. Each completed online trials combining a stress-induction exercise with exposure to virtual interior environments representing classrooms, corridors and stairwells. The stress task required rapid arithmetic under noisy, socially pressurised conditions. Participants then viewed digital images of interiors rendered at four levels of biophilic design: Level 0 with no natural elements; level 1 introducing natural light, depth and prospect; level 2 adding natural analogues – such as organic colours, textures and materials; and level 3 incorporating plants, daylight and natural materials.

Psychological responses were measured using the positive and negative affect schedule (Panas). Pairs of adjectives were mapped to the four theoretical constructs: relaxed/irritable (recovery); attentive/fatigued (attention); self-assured/frightened (refuge); and inspired/downhearted (inspiration). Comparing post-stress and post-exposure ratings allowed the authors to calculate the degree of emotional recovery attributable to each biophilic level.

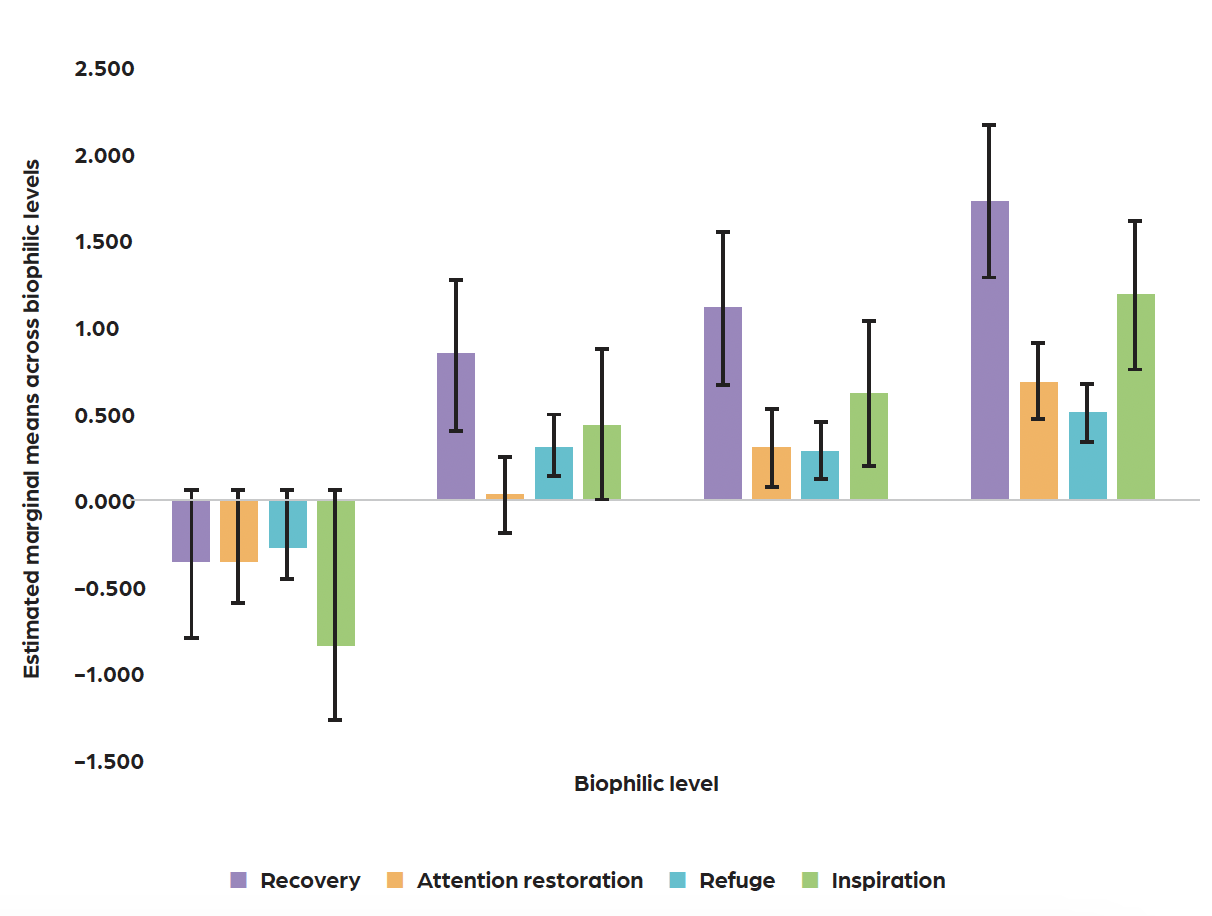

Across all constructs there were statistically significant improvements as biophilic richness increased (p < 0.001). At level 0, sterile interiors produced negative scores, indicating a further deterioration in mood. In contrast, levels 1-3 generated progressively larger positive effects, reaching mean improvements of +1.74 for recovery and +1.19 for inspiration at level 3. Most increments between levels were significant, showing a dose-response relationship between biophilic intensity and psychological benefit. Simple ‘liking’ ratings aligned with the Panas outcomes: only the most biophilic environments were viewed favourably. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Changes in reported mood across biophilic design levels Source: bit.ly/45bw0J2

No significant correlations were found with demographic variables such as age, gender, ethnicity, or whether participants lived in urban or natural settings. The responses appeared broadly universal, supporting the proposition that biophilic tendencies may be widely shared.

The inclusion of ‘inspiration’ as a measurable construct marks a conceptual development. Whereas earlier theories focus on restoring depleted states such as stress or fatigue, the inspiration hypothesis aligns with positive psychology, which emphasises human flourishing.

Feeling inspired represents a proactive emotional condition that can underpin creativity and engagement, extending the rationale for biophilic design into educational and innovation-focused settings.

The authors also suggest that the absence of biophilic features may contribute to sick-building syndrome (SBS). While SBS is often linked to air quality or comfort parameters, sensory monotony, lack of natural cues and visual sterility may also act as psychological stressors. Conversely, introducing layered natural elements, including spatial variation, organic materials and greenery, produced measurable emotional gains.

Like all laboratory-based work, the study has limitations. Digital imagery captures only the visual dimension and not the full sensory spectrum of real environments. Future research, the authors note, should incorporate additional sensory cues and objective physiological measures, and be validated in live building contexts. They also highlight the need to explore individual differences, such as personality traits and neurodiversity. Nevertheless, the controlled approach suggests an association between environmental design variables and affective outcomes, although further validation is required.

Viewed through the lens of building services and architectural engineering, the implications are noteworthy. Design decisions influencing light, air, materials and spatial form have psychological as well as physical effects. Incorporating biophilic principles within schools, offices and healthcare facilities has the potential to support reduced stress, improved concentration and greater creative engagement. At a broader scale, enriching urban buildings with natural qualities may help mitigate some of the psychological pressures associated with city living.

The research team proposes that biophilic design may represent more than an aesthetic strategy, noting potential public health implications. Their findings suggest its effects could extend beyond comfort and energy performance into emotional and cognitive domains. In showing that inspiration may be influenced by environmental design, the study highlights an area warranting further investigation. In short, the paper suggests that buildings that strengthen our connection with natural elements may help us feel more alive.

Contributors sought: A biophilic design guide is being developed, with a workshop in early 2026. To contribute, email Dr Yangang Xing FCIBSE at yangang.xing@ntu.ac.uk

References:

1 Xing Y et al, ‘Exploring biophilic building designs to promote wellbeing and stimulate inspiration’, PLOS One, 2025. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0317372