CPD sponsor

As buildings move away from combustion-based heating, air handling technology is evolving to meet the demand for all-electric solutions. Integrating heat pumps within air handling units (AHUs) allows a single system to deliver efficient heating, cooling and ventilation. This CPD explores how this approach supports both decarbonisation goals and modern expectations for comfort and performance.

Modern AHU designs combine the established functions of filtration, heat recovery and airflow management, and increasingly offer the option of reversible heat pump operation to provide efficient, all-electric comfort conditioning – particularly in commercial and institutional buildings. Such systems are now common in new-build and retrofit applications, driven by advances in component efficiency and control capability, and by regulations and standards promoting high-performance ventilation solutions.

When a heat pump is incorporated with an AHU installation – either as an integral module or as external plant serving the coils – the system becomes capable of delivering space heating and cooling directly through the supply air stream. This integration can take several forms: a factory-assembled weatherproof package containing compressors, coils and fans; an indoor AHU connected to a remotely mounted air-to-water or water-to-water heat pump; or an arrangement that draws heat from the exhaust air stream to supply tempered outdoor air. Each configuration can be adapted to the building’s scale and energy strategy, provided that air, water and refrigerant systems are designed as a coordinated whole.

Heat pumps used with AHUs are commonly classed by their energy source. Air-to-air systems extract heat from ambient air and deliver it directly to supply air through a refrigerant coil that serves alternately as condenser or evaporator, depending on the operating mode. This avoids hydronic circuits and is compact, though it requires effective frost protection and defrost control at low outdoor temperatures. Air-to-water systems use a separate heat-exchange loop, generating hot or chilled water that is circulated to one or more AHU coils.

This approach offers flexibility and is well suited to multi-zone buildings and retrofits where hydronic coils already exist. In heating mode, air source heat pumps (ASHPs) cannot achieve the same flow and return temperatures as conventional legacy boilers, so coils may need to be enlarged, or additional rows added, to maintain duty.

There are, however, benefits in reducing flow temperature, as it reduces the compressor lift across the heat pump and, as noted by CIBSE AM17,1 each 1K reduction in lift can raise the coefficient of performance (COP) by 2-3% – so, for example, a 10K reduction may increase COP by around 20%. (Compressor lift is the temperature difference between the evaporating and condensing conditions within a heat pump; reducing this lift lowers compressor work and improves overall system efficiency.)

Ground source heat pumps (GSHPs) provide stable operation by drawing energy from boreholes or horizontal ground loops, where temperatures remain practically constant throughout the year. Configured as water-to-water systems, they can feed multiple AHUs through a common heating and cooling network, maintaining very high seasonal performance factors.

The installation cost is greater, but operational energy use is correspondingly lower, making this option attractive for large estates or new-build campuses. Exhaust air heat pumps provide another efficient configuration, recovering heat from the extract air to warm supply air or a hydronic circuit. Because extract air temperatures rarely fall below 18°C, frost is avoided and the recovered energy offsets or replaces conventional heat recovery.

In modern packaged AHUs, the combination of a heat pump circuit and energy-recovery device delivers particularly high efficiency. The system is typically arranged so that the supply air first passes through a plate or rotary exchanger that transfers sensible and, potentially, latent energy from the exhaust airstream, reducing the load on the subsequent heating or cooling coil. The heat pump then trims the air temperature to meet the supply air setpoint, providing additional heating or cooling as required.

In mild weather, the initial heat exchanger alone may satisfy the load, without activating the heat pump. This dual-stage arrangement not only improves seasonal performance, but also limits frosting, as the heat pump’s evaporator coil operates above freezing. Control sequences prioritise the initial exchanger and engage the active stages only when needed.

Packaged AHUs with integral heat pumps are increasingly supplied as fully factory-assembled systems. These include all major components – fans, filters, coils, compressors, expansion valves and controls – within a single enclosure that can be installed either outdoors or in a plantroom.

Factory-assembled casings typically comply with BS EN 18862 mechanical performance requirements, achieving leakage class L2 or better and thermal class T2, indicating low air leakage and good thermal insulation of the unit housing.

By delivering both ventilation and thermal conditioning from one assembly, such units simplify installation, reduce plantroom footprint and eliminate the need for separate chiller or boiler plant. Factory assembly ensures consistent performance, and modern variable-speed compressors and electronically commutated (EC) fans allow efficient part-load operation.

For larger or more complex buildings, the same principle applies using central AHUs connected to external heat pump plant. The external units, which are commonly air-to-water heat pumps with integral refrigerant-to-water heat exchangers, supply low-temperature hot water or chilled water to multiple AHUs. The use of such external monobloc heat-pump arrangements removes the need to route refrigerant pipework to the AHU, which is particularly advantageous when using refrigerants designated as A3 (such as R290 (propane)).

This configuration provides greater flexibility in plant positioning and maintenance, while the hydronic circuit additionally acts as a thermal buffer to reduce compressor cycling. It can also simplify installation, as no internal refrigerant work is required. Water temperatures are modulated according to room loads, with higher temperatures supplied only when demanded by the AHU heating coils.

When several AHUs share a common circuit, supervisory controls can adjust the flow temperature from the heat pump dynamically to satisfy all loads at the lowest possible lift in temperature, thereby improving system COP. (See the boxout, ‘Smart plant integration’, for an example of how coordinated control can optimise AHU and heat pump performance.)

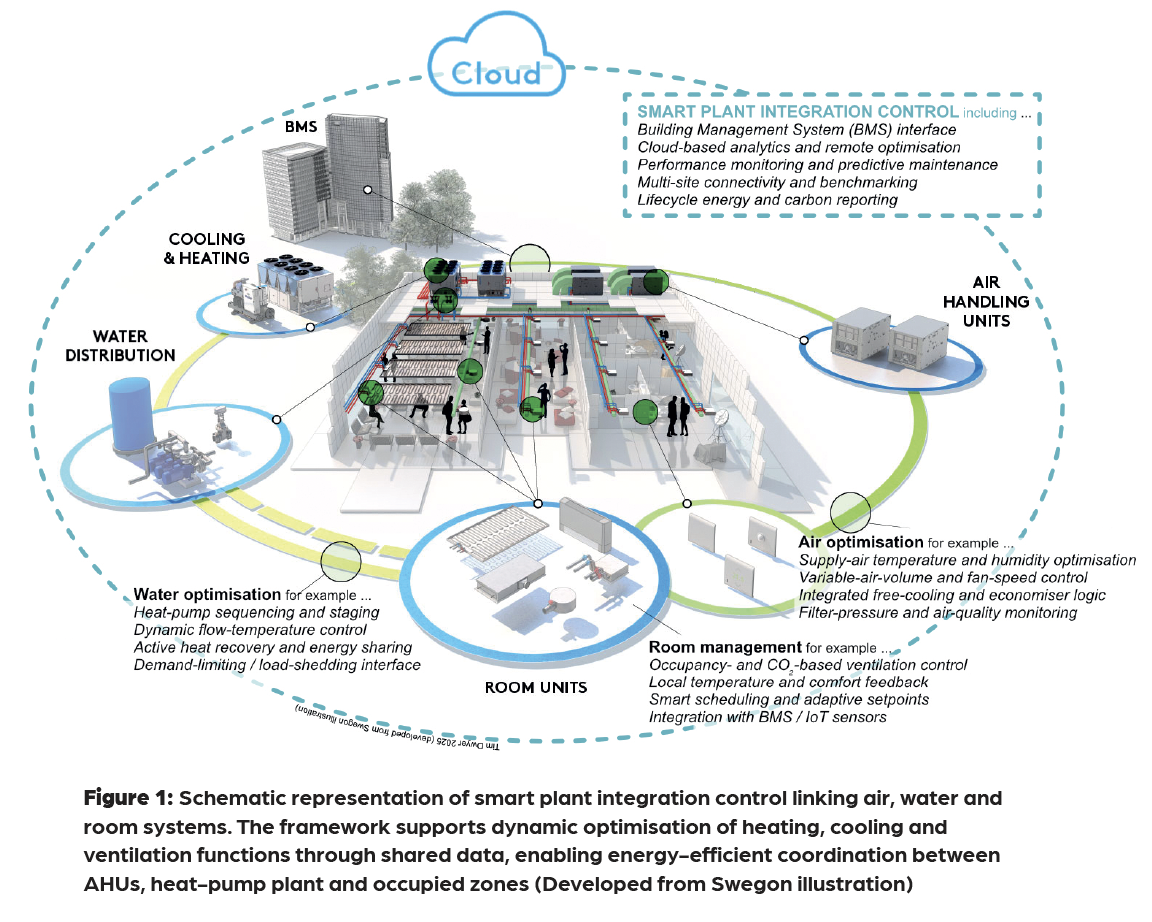

Smart plant integration

Coordinating the operation of air handling units and central heat pump plant through smart plant integration control can significantly enhance overall efficiency. Instead of maintaining fixed design-day water temperatures, the system continuously adapts heating and cooling setpoints to reflect the combined demand from all connected AHUs.

Each 1K rise in chilled water temperature can reduce compressor energy use by around 3%, while a 1K reduction in heating water temperature can save about 2.5%. Over a typical year, this adaptive control can readily achieve 10-15% energy savings compared with constant-temperature operation.

By harmonising the behaviour of plant and ventilation systems, smart integration also smooths compressor cycling, simplifies installation, and maintains stable indoor comfort while improving seasonal carbon performance.

Regardless of configuration, several design fundamentals remain constant. Coils must be selected for the lower temperature differentials of heat pump operation and sized to maintain required heating and cooling capacity at reduced flow temperatures. For hydronic coils, freeze protection may be required when outdoor temperatures fall below zero, achieved either through antifreeze mixtures, preheat coils, or airflow bypass during extreme cold.

Frost formation on air source coils can significantly reduce efficiency. Reverse-cycle defrost remains the most common mitigation method, but modern systems use sequential or demand-based defrost to minimise disruption. In packaged units with multiple refrigeration circuits, coils defrost alternately so that warm supply air is maintained continuously. In mixed-air systems, partial recirculation or preheating of outdoor air can also prevent frosting under cold, humid conditions.

Control and sequencing are central to efficient operation. Supply air temperature is maintained by modulating compressor capacity, refrigerant flow or water-valve position, and is often linked to outdoor temperature (weather compensated) to reduce flow temperature in mild weather.

Humidity control can be achieved by reusing condenser heat for post-cooling reheat, avoiding additional electric load. When both heat recovery and a heat pump stage are present, control logic should prioritise the initial heat exchanger, enabling the heat pump only when recovery cannot meet the setpoint. During suitable conditions, free-cooling bypass dampers allow outdoor air to deliver cooling without compressor operation.

Safety and protection devices – including freeze thermostats, pressure cut-outs and anti-short-cycle timers – are vital for reliability. Integration with the building management system (BMS) allows monitoring of compressor status, fan speed and energy performance, as well as coordinated start-up to avoid electrical demand peaks.

CIBSE AM171 highlights that careful commissioning and seasonal tuning are essential to achieve design performance. Poorly sequenced controls, such as maintaining unnecessarily high water temperatures or simultaneous heating and cooling, can significantly degrade efficiency.

When these control principles are applied effectively, monitored data (from UK and Europe) show that seasonal performance factors (SPF) for ASHP AHUs typically range from 3.0 to 4.5 in heating mode and 2.5 to 4.0 in cooling mode, with GSHP and exhaust air systems performing even better.

Continuous monitoring and periodic review of trend data allow operators to refine temperature setpoints, defrost strategy and scheduling, helping to maintain the expected seasonal performance in day-to-day operation.

Maintenance requirements for heat pump AHUs are broadly similar to those for conventional air handling systems, with additional attention needed for the refrigeration components. Filters, fans and dampers follow standard intervals, while coils and compressors require inspection for cleanliness and refrigerant integrity. Outdoor coils must be kept free of debris to maintain heat transfer, and technicians should be familiar with safe refrigerant handling and diagnostic procedures.

Component life expectancy should be broadly similar to conventional systems, with scroll compressors typically achieving 15-20 years of service. Electronic controls may require software updates or replacement mid-life to maintain cybersecurity and manufacturer support.

The initial cost of a heat pump-equipped AHU is higher than that of a traditional system with separate boiler and chiller plant, but installation is simpler and faster, and operational savings can be significant. The elimination of natural gas infrastructure, flues and combustion air requirements offsets part of the capital cost, and operating efficiencies of three or more units of heat for each unit of electricity deliver competitive running costs, even at current energy tariffs.

As the electricity Grid continues to decarbonise, carbon intensity and whole-life emissions will reduce further, strengthening the case for all-electric ventilation and conditioning.

The success of any installation ultimately depends on coordinated design and commissioning. The air, water and refrigerant systems must be treated as a fully integrated thermal process, with coil selection, airflow paths and control sequences tuned to operate efficiently across seasons.

Electrical supply and peak-load management must be considered early in the design process to ensure capacity for compressors and controls. In retrofit projects, the potential to reuse existing AHUs with new low-temperature coils or external heat pump plant can provide an effective decarbonisation step with less disruption.

A commercial installation at a UK retail site, as detailed in the boxout ‘Retail retrofit’, replaced gas boilers with external monobloc air-to-water heat pumps using a low-global warming potential (GWP) natural refrigerant. The seasonal COP values exceeded 4 and the installation achieved a 74% reduction in equivalent carbon impact compared with gas heating.

Retail retrofit

A UK retail site retrofit demonstrates the practical application of natural refrigerant heat pumps for low-temperature heating. The project replaced around 250kW of gas-fired boiler capacity with externally mounted, factory-built air-to-water units using propane (R290), achieving equivalent heating performance while eliminating onsite combustion.

Two fully inverter-driven, reversible air-to-water R290 heat pumps provide a combined heating capacity of 256kW with a 23% turndown ratio. These particular systems, shown in Figure 2, include ATEX-rated leak detection and onboard safety management.

Figure 2: Externally installed air-to-water monobloc heat pumps using propane (R290, A3 refrigerant, GWP ≈ 0.02) supply 40-55°C heating water to AHUs in a UK retail installation achieving a seasonal COP ≈ 4.5 (Source: Swegon)

The design incorporates two independent refrigerant circuits for staged operation and defrost control, variable speed compressors for smooth modulation and low starting current, and a wide operating envelope capable of maintaining 60°C leaving-water temperature at -10°C outdoor temperature.

This system serves the comfort heating application with a 45°C supply and 39°C return temperature. Continuous optimisation through BMS-linked remote monitoring – adjusting compressor sequencing, setpoints and pump operation – yielded a further 15% energy reduction.

The project also illustrates how locating the refrigerant circuit outdoors can enable and simplify the safe use of A3-designated refrigerants – those that are designated ‘low toxicity’ (practically, R290 is non-toxic in normal use) but high in flammability – while delivering high efficiency and very low environmental impact.

Once commissioned and optimised, integrated heat pump AHUs can deliver stable comfort, high indoor air quality, and measurable energy and carbon savings. They provide a straightforward, scalable route to electrification of heating and cooling in non-domestic buildings and – when designed and commissioned in accordance with prevailing standards – these systems offer efficient, reliable and fully electric solutions, reducing emissions while maintaining environmental quality.

© Tim Dwyer 2025.

References:

1CIBSE AM17: 2022 Heat pumps for large non-domestic buildings, CIBSE 2022.

2 BS EN 1886: 2007 Ventilation for buildings – Air handling units – Mechanical performance, BSI 2007.