The Science and Industry Museum in Manchester stands on one of the most significant industrial heritage sites in the world – the terminus of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the world’s first purpose-built passenger line. What took place here in 1830 revolutionised trade, travel and technology. It was where science met industry, sparking the modern era.

Project team

Client: Science and Industry Museum

Architect: Carmody Groarke

Main contractor: HH Smith & Sons

M&E engineer: Max Fordham

MEP contractor: Murray Building Services

Structural engineer: Conisbee

Borehole consultant: Advisian

Heritage consultant: Donald Insall Associates

Fire engineer: Design Fire

The museum’s site includes the world’s oldest-surviving passenger railway station and the first purpose-built railway goods warehouse. Among its landmark buildings is the Power Hall, built in 1855 as the shipping shed for Liverpool Road Station. Since 1983, it has been home to a collection of working steam engines that once powered the mills and factories of the Industrial Revolution.

Now, after a major refurbishment, the Power Hall is again celebrating engineering innovation – this time through technologies that are shaping the low carbon revolution.

Alongside one of the UK’s largest collections of fossil fuel-powered engines, visitors can see how a scheme designed by Max Fordham is using four water source heat pumps (WSHPs) and an electric steam boiler to provide low carbon heat and power to the Grade II-listed hall.

A personal connection

Max Fordham’s involvement with the museum began in 2019, when director Iain Shaw was invited to visit it by an architect friend. It was a return to a formative place for Shaw. ‘I remember visiting as a child,’ he says. ‘The smell of hot oil, the rhythmic pulse of the engines being driven by steam; there’s a visceral sense of Victorian innovation. It’s the place that inspired me to become an engineer.’

At the time of his visit, plans were being developed to refurbish the 108m-long Power Hall to protect the structure and heritage. A 4MW gas boiler was being used to generate steam for the engines, but the system was inefficient: waste heat from the oily steam condensate was discharged to the atmosphere via a cooling tower and the condensate water was dumped to drain. A steam-fed space heater had stopped working, leaving the hall unheated.

During his tour, Shaw also visited the 1830 Warehouse, another of the site’s original buildings. Within it was a well that once supplied water to the steam-powered cranes used to load goods from the railway. ‘As soon as I saw the well, I said, “there’s groundwater down there we could use”,’ recalls Shaw.

The Grade II-listed Power Hall was the shipping shed for Liverpool Road Station

By the end of the visit, he had sketched out a concept for a fully electric, closed-loop steam system that could provide low carbon steam to the exhibits, and space heating to the Power Hall and the 1830 Warehouse. The proposed design was built around three interlinked systems:

- An electric steam boiler to supply the historic engines

- Boreholes providing a water source for heat extraction and rejection from the steam condensing process

- WSHPs to supply low carbon heating when the steam system is offline.

The concept was developed in partnership with the museum to form a bid to the UK government’s Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme, administered by Salix Finance. The scheme projected annual carbon savings of 515 tonnes, based on the Grid carbon factor at the time.

In 2021, the museum secured £4.3m to decarbonise the Power Hall and 1830 Warehouse, and Shaw’s low carbon services concept became a central element of the Power Hall restoration project, led by architects Carmody Groarke.

Preserving history, upgrading performance

The building’s refurbishment included major conservation work: repairs to the historic roof timbers; a new insulated roof, using vapour-permeable wood-fibre insulation compatible with the building’s original breathable fabric; and reinstatement of the salvaged natural slates. Arched windows and rooflights were replaced with double-glazed units to improve efficiency while maintaining the original appearance. Inside, energy-efficient LED lighting was installed and the central loading platform reinstated.

Externally, new boreholes were drilled beneath the listed cobbled courtyard. A trench was excavated for a new high-voltage cable to power the electric steam boiler.

‘We were fortunate,’ says Shaw, ‘that the archaeological survey didn’t uncover anything that prevented us from proceeding with the boreholes or trench.’

Two 80m-deep abstraction boreholes in the museum’s Upper Yard draw groundwater from the aquifer for heat supply and rejection. Originally, a single borehole had been predicated to provide sufficient water for the scheme, but this proved not to be the case, so a second borehole was drilled. This provided the expected volume of water, so the original borehole is now used as a backup. A third borehole, in the Lower Yard, returns water to the aquifer after it has passed through the heat-exchange systems.

The new steam plant and heat pump installation are all on display as a new exhibit

The design also makes use of a Victorian brick culvert to discharge any surplus groundwater that cannot be reabsorbed by the aquifer to the adjacent River Irwell. The Environment Agency requires that the discharge water temperature remain below 23°C.

Steam goes electric

At the heart of the Power Hall’s new heating and exhibition system is a 780kW electric steam boiler, powered by green electricity. The boiler provides steam to the pistons that drive the historic engines via two circuits – one high-pressure and one low-pressure.

With no technical data for the 19th-century machinery, Max Fordham’s team had to estimate the engines’ steam consumption and condensate production during startup and steady running.

‘What we’ve got is a standard electric steam boiler connected to Victorian engines, with only a vague idea of how they perform,’ says James Cornes, principal engineer at Max Fordham.

Close collaboration between the engineers, the MEP contractor Murray Building Services, and the museum’s technical team was critical. ‘Getting the engines to run properly on the new system was quite a challenge,’ Cornes adds.

A new steam pipework system collects the oily steam/condensate mix and returns it to the boiler using gravity. The condensate mix passes through filters and a skimming tank to separate the oil before the steam condensate flows through a heat exchanger that cools it to liquid and valuable heat is captured.

‘You have to turn the steam back into liquid before you can put it back in the boiler, so there is abundant heat to recover and reuse,’ says Shaw.

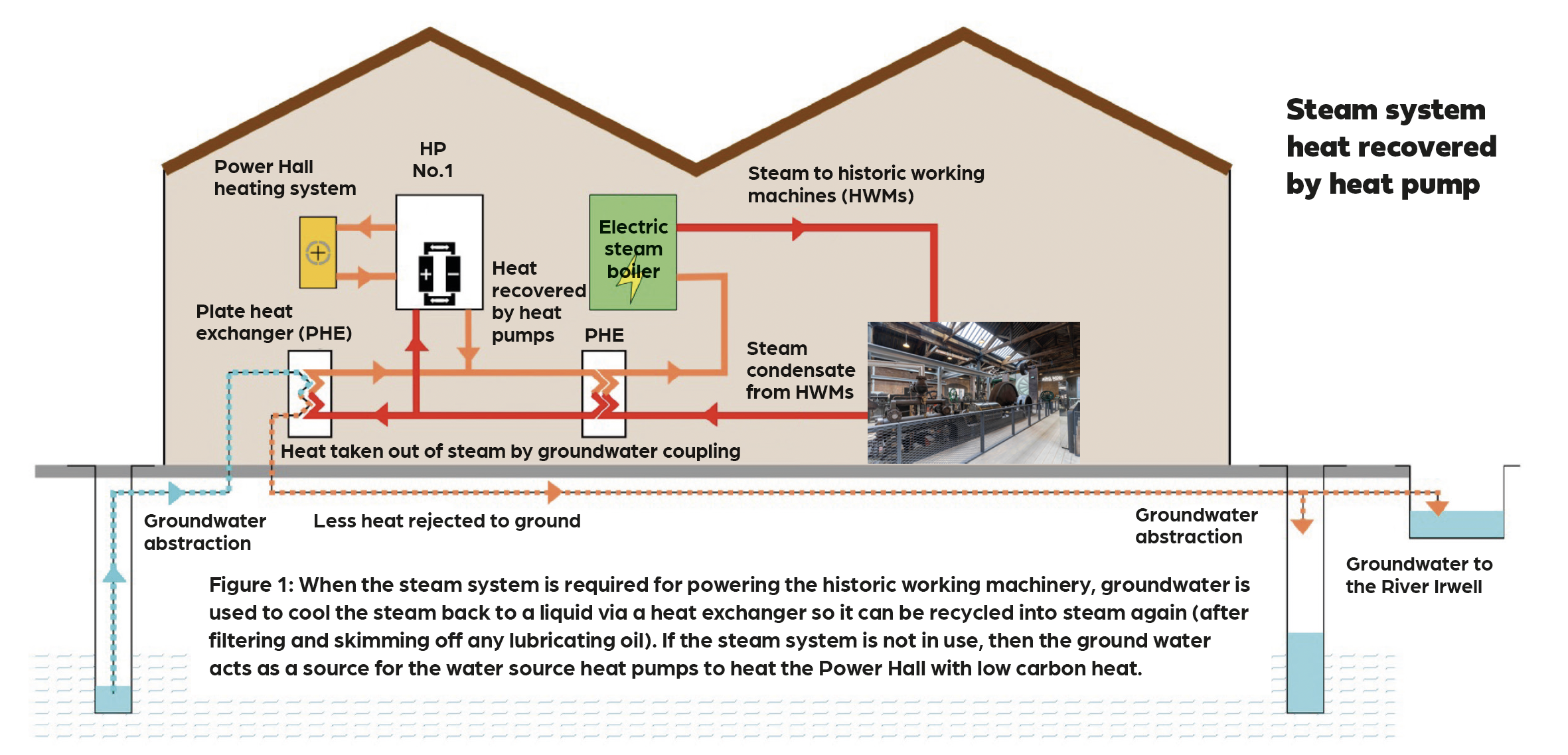

In winter, the heat recovered from this process via the heat exchanger provides space heating for the Power Hall through a separate loop (see Figure 1).

Heating the hall

Four WSHPs connect to the Power Hall heating loop. Depending on the loop’s temperature, the recovered heat can be used directly for heating or upgraded by the heat pumps to around 50°C. This heat is piped to fan coil units hidden beneath the reinstated platform, delivering displacement heat to the lower part of the hall. This arrangement ensures the temperature at engine level remains above dew point, preventing condensation on the historic machinery.

‘The space heating isn’t provided for visitor comfort,’ Shaw emphasises. ‘It’s to protect the exhibits.’

After passing through the WSHPs, the Power Hall heating loop transfers its remaining heat to the borehole water via another heat exchanger. The warmed groundwater is then piped to the 1830 Warehouse, where another WSHP extracts further energy to provide space heating for that building before the borehole water is reinjected into the aquifer, or discharged to the river.

A museum volunteer prepares the Durn Mill steam engine to run

Smarter, leaner operation

When the museum first opened, the gas-fired steam generator ran continuously from the moment the doors opened until the last visitor left, with all engines operating. Under the new low carbon regime, all the engines remain connected to the steam circuit, but not all the engines run. Their running schedule has also been rationalised to a maximum of three hours per day.

‘It reflects a more considered approach to energy consumption,’ Shaw explains.

When the steam boiler is offline, the heat pumps are sized to provide space heating using heat obtained from the borehole water. ‘We take a bit of heat out of the groundwater, elevate it with the heat pump, and use it to heat the Power Hall,’ Shaw says.

In summer, when there is no need for space heating, the steam boiler will continue to provide steam to the exhibits, and borehole water will continue to remove heat from the condensate circuit before it is returned to the steam boiler.

Without the additional demand from space heating, more heat is rejected into the groundwater circuit. To ensure that water is returned to the aquifer at the correct temperature, the building management system (BMS) automatically increases the abstraction pump speed, boosting flowrates up to 20 litres per second.

‘The system relies on the three subsystems being fully integrated through the BMS,’ Cornes explains.

Environmental control and visitor comfort

The refurbished Power Hall also benefits from discreet environmental control measures. To prevent overheating from solar gain and heat generated by the engines, the architects concealed motorised louvres within the timber panelling surrounding the glazed arched openings. These open automatically under BMS control to enhance natural ventilation when internal temperatures rise.

The new steam plant and ground source heat pump installation are all on display as a new exhibit in the Power Hall, detailed in collaboration with Carmody Groarke. It is part of the Listed Building Consent, which required the story of the decarbonisation to be told.

The Power Hall reopened to the public on 17 October, revealing a striking juxtaposition: Victorian steam engines powered by modern, low carbon technology.

The new exhibit includes an interactive touchscreen that explains how the heat pumps, boreholes and electric steam boiler work together to deliver renewable heat to the historic building.

For visitors, the latest exhibit provides a tangible link between the mechanical ingenuity of the 19th century and the sustainable engineering of today. As Shaw reflects: ‘It feels entirely fitting that the birthplace of the first Industrial Revolution is now home to the technologies driving the next one’