The UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard (UK-NZCBS) is one of the most important initiatives the UK built environment sector has produced in years. It has been developed to answer the question: what does it mean for a building to be aligned with a net zero carbon world?

For years, net zero carbon has been used inconsistently, with little alignment between claims and outcomes. In 2019, the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC) started developing an agreed industry definition with its Net Zero Carbon (NZC) framework. However, the UK- NZCBS – which was partially built on the work of the NZC framework – is a more comprehensive standard, with greater detail and definitive limits.

What is the UK-NZCBS?

It is a standard that provides the industry with a consistent approach to assessing whether a building can be defined as net zero carbon.

Adopting the standard means that a building is aligned with a net zero carbon future. It takes into account operational and embodied carbon, with measurable limits and requirements, and those targets become more ambitious over time, in line with the UK’s carbon budgets.

As the focus is on alignment, offsetting is not required. Crucially, verification of net zero carbon performance will only be for buildings that are built and in operation – so claims can only be made by projects that have delivered against the standard in practice.

The UK-NZCBS has been developed by key industry bodies, including RIBA, LETI, CIBSE, RICS and the UKGBC, and there has been input from hundreds of industry professionals, who have formed task and sector groups to review the detailed requirements. Overall, it has been a great example of industry collaboration.

The standard is in its pilot stage, with real projects being tested against it. Version 1 will be published at the end of this stage, at which point buildings can be submitted for formal verification.

The pilot sets the following requirements:

- No fossil fuels in the project (with some exceptions for life-safety backup systems)

- Appropriate energy use intensity (EUI) limits (to building type and new/retrofit projects)

- Appropriate upfront carbon limits (to building type and new/retrofit projects)

- Minimum PV generation requirement

- Maximum allowable refrigerant global warming potential (GWP).

Additionally, it requires that projects report on:

- Peak energy demand

- Whole life carbon (WLC).

All the limits are set by the year in which the project starts on site. The limits for 2025-26 align with current best practice and become gradually harder to achieve.

Inevitably, there is push-back on some elements of the standard, focusing on three broad areas: retrofit has lower upfront carbon targets than new builds; there is no overall WLC limit; and some of the limits are unfeasible in practice. It is worth exploring these points, but none of them challenges the overall picture of a standard that is an excellent framework for delivering net zero carbon-aligned buildings.

The UK-NZCBS is aiming for a standard that is technically rigorous and operationally workable, which is hard, and the right trade-offs have been made between both factors.

Figure 1: The ICTA Rooftop Greenhouse Lab

Retrofit versus new build

The suggestion that more onerous retrofit limits will make demolition more attractive does not stand up to scrutiny. Our experience shows that the gap in upfront emissions between retrofit projects and new-build ones is very wide. So while the absolute limits for retrofit are lower, they are much more achievable than for most new-builds.

Moreover, where substantial extensions or rebuilds form part of a retrofit scheme, these elements are rightly assessed against new-build limits. The structure rewards true retrofit, not superficial reworking.

Taking this approach is supported by data collected in the development of the UK-NZCBS and from the Greater London Authority’s analysis during the M&S Oxford Street inquiry. Having separate retrofit and new-build targets works well – it incentivises retrofit while still capping the upfront carbon to encourage sustainable practices from project teams.

Calls for instituting an absolute WLC limit for projects sound reasonable, especially as this metric encompasses the total impact of a building over its lifetime, but it will be hard to make workable in practice.

Upfront embodied carbon and energy use are measurable and verifiable now, and the data on which they are based is reliable. By contrast, WLC targets can only be set by using much more uncertain assumptions about material lifespans, future electricity and material manufacture decarbonisation, and end-of-life scenarios.

We are limited by what is knowable about a building over its lifetime. While there are no limits on WLC, the standard does require reporting against the metric, and the intention is to introduce WLC limits in future.

However, by setting limits on upfront carbon, energy use, refrigerant GWP and minimum PV generation, and by banning fossil fuels, almost all aspects over which the design team has influence in regard to WLC emissions of a building are addressed.

Cranmer Road, King’s College

Operational performance: 71kWh.m-2 per year

Meets NZCBS target. Limits for commercial residential:

(2025 new build) 75kWh.m-2 per year

(2028 new build) 70kWh.m-2 per year

Summary

- Passivhaus

- CLT panels and slab structure

- Glazing sized for daylight – no more

- Approx 200 to 300mm of EPS or XPS insulation

- Airtightness < 0.6 ach/hr at 50Pa

- Triple-glazed windows

- MVHR

- Low-energy lighting

- Direct electric radiators, direct electric POU hot water

- lWater-efficient showers

Limits need to reflect reality

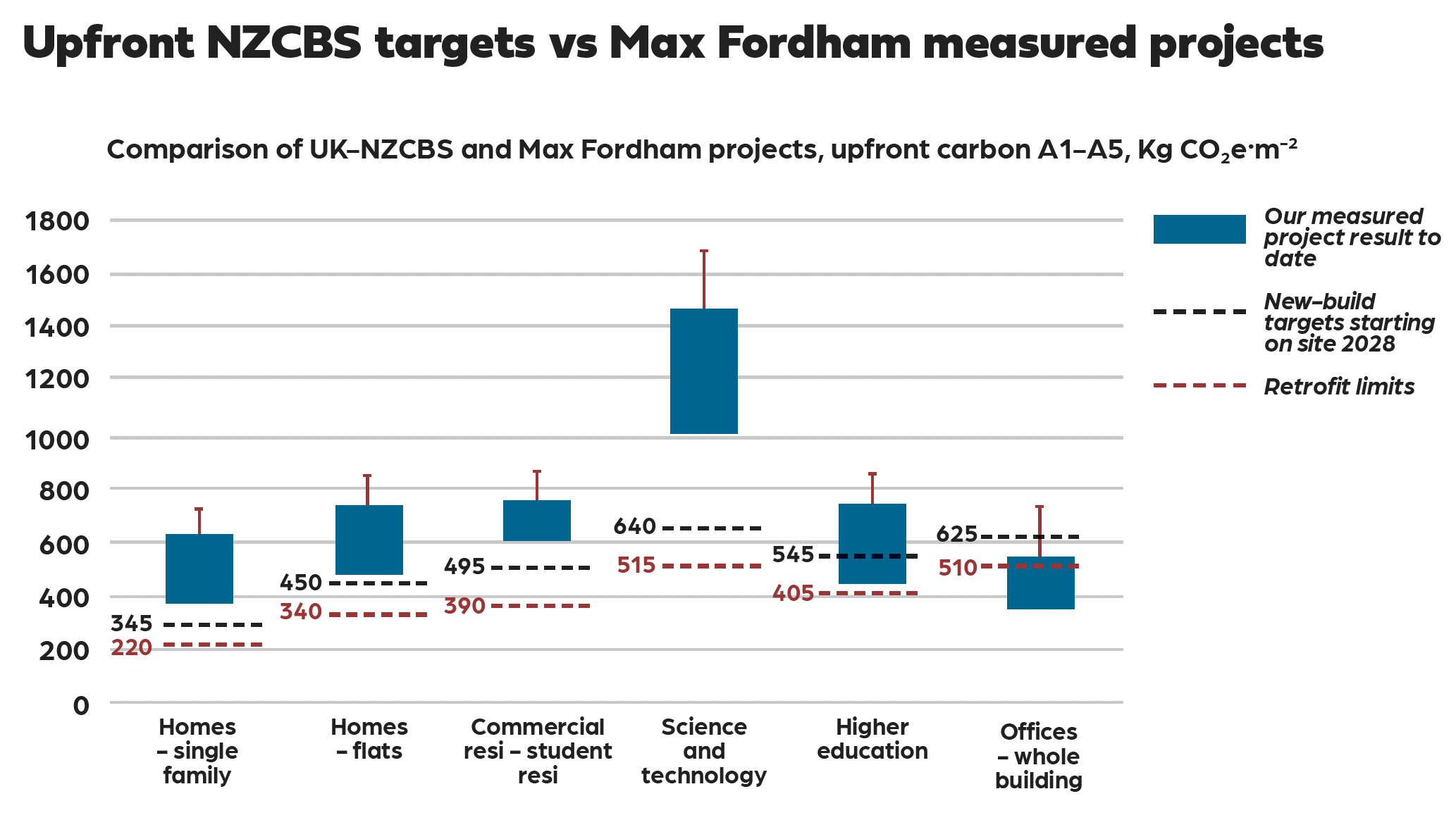

Some limits set by the pilot standard will be challenging. Max Fordham is involved with some of the most environmentally ambitious projects in the UK and has an experienced WLC modelling team. However, none of our completed new-build residential projects (single family, flats or student resi) meets the upfront carbon limits set by the UK-NZCBS. This includes timber-frame dwellings.

Only one of the new-build offices we have worked on, a predominantly cross-laminated timber (CLT) building, has achieved the office new-build limits. However, we are working on several deep-retrofit and extension projects that comfortably meet the retrofit targets.

EUI targets are often the biggest retrofit challenge, and we feel more calibration of the targets is needed. The limits for new-build schools are more stringent than any of our projects have achieved. This includes a recent all-electric Passivhaus primary school. The residential EUI limits are similarly challenging and don’t align with real UK residential energy use data.

Max’s House, for example, does not meet the standard even though it is a Passivhaus-verified net zero carbon home with incredibly low space-heating design (see details in this story at www.cibsejournal.com).

Nigel Banks, Octopus Energy’s technical director for zero bills homes, has highlighted that the average unregulated energy use in UK homes is 35kWh.m-2 per year, which means that – even with Passivhaus-aligned heating and hot-water demand – the probable use in homes will be 50Wh.m-2 per year. The UK-NZCBS target is just 45Wh.m-2 per year for single family housing and 40Wh.m-2 per year for flats.

On the other hand, we think that the sports building energy limits aren’t tough enough. The University of Portsmouth’s Ravelin Sports Centre, on which we worked, has an actual energy use that would meet the limits right up until 2050.

Ravelin Sports Centre, University of Portsmouth

Operational performance: 100-128kWh.m-2 per year

Meets 2028 NZCBS target (~10% of typical UK sports centre)

Limit for UK sports centre (2028 new build): 174kWh.m-2 per year

Features

- Compact form factor

- Extensive daylighting

- Mixed-mode ventilation and heat recovery from cooling, ventilation, waste pool water

- Leanly sized air source heat pumps

- PV array to meet 20% building energy demand

- Soft Landings throughout

Max’s house/6 Camden Mews

Operational performance: 63kWh.m-2 per year

Project space-heating performance: 5kWh.m-2 per year

Project onsite energy: 48kWh.m-2 per year

Fails to meet NZCBS target. Limit for new family home: 45kWh.m-2 per year

Features

- Passivhaus design completed in 2019

- Highly insulated: ~250mm mineral wool and100m wood fibre. Motorised shutters minimise heat loss

- Space heating met by 2kW in-duct electric heater

- Domestic hot water produced by high-temperature air source heat pump feeding water cylinder

- Highly insulated roof alongside green roof areas

A massive step forward

The standard is an excellent platform for the industry to address its climate impacts, setting clear limits for the big issues. There is work to do to refine and adjust specific criteria and limits, and we expect this to be the outcome of the pilot.

What we have already is a standard that sets a clear direction, is rooted in evidence, and has requirements to measure projects against.

While formal verification of a project will not be possible until Version 1 appears, I would encourage teams to assess performance against the standard. Doing so will help them understand where they will need to improve to ensure projects are compatible with a net zero future. l

Read Max Fordham’s Beyond Net Zero white paper at bit.ly/CJBNZMF25

About the author

Henry Pelly is a sustainability consultant at Max Fordham