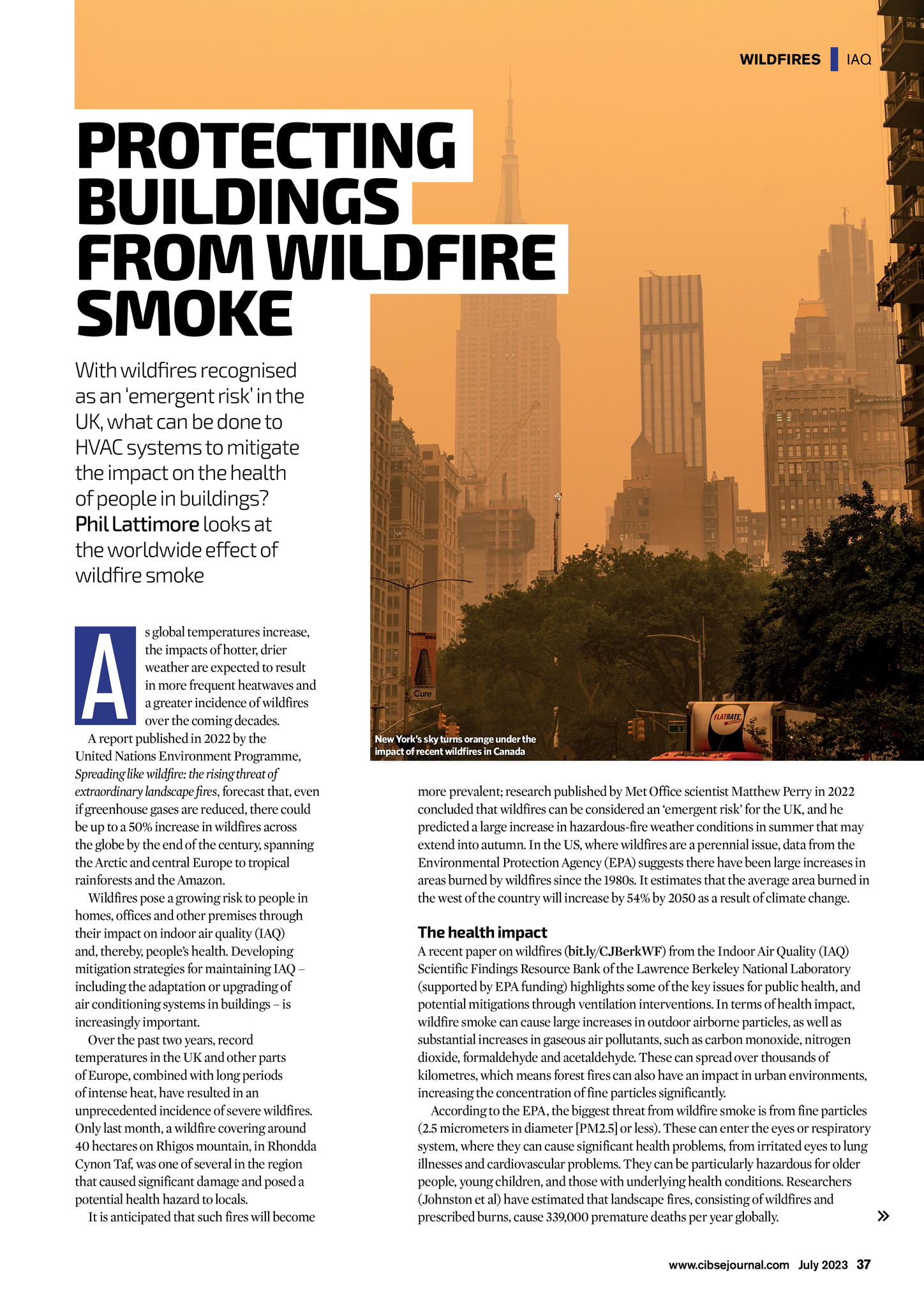

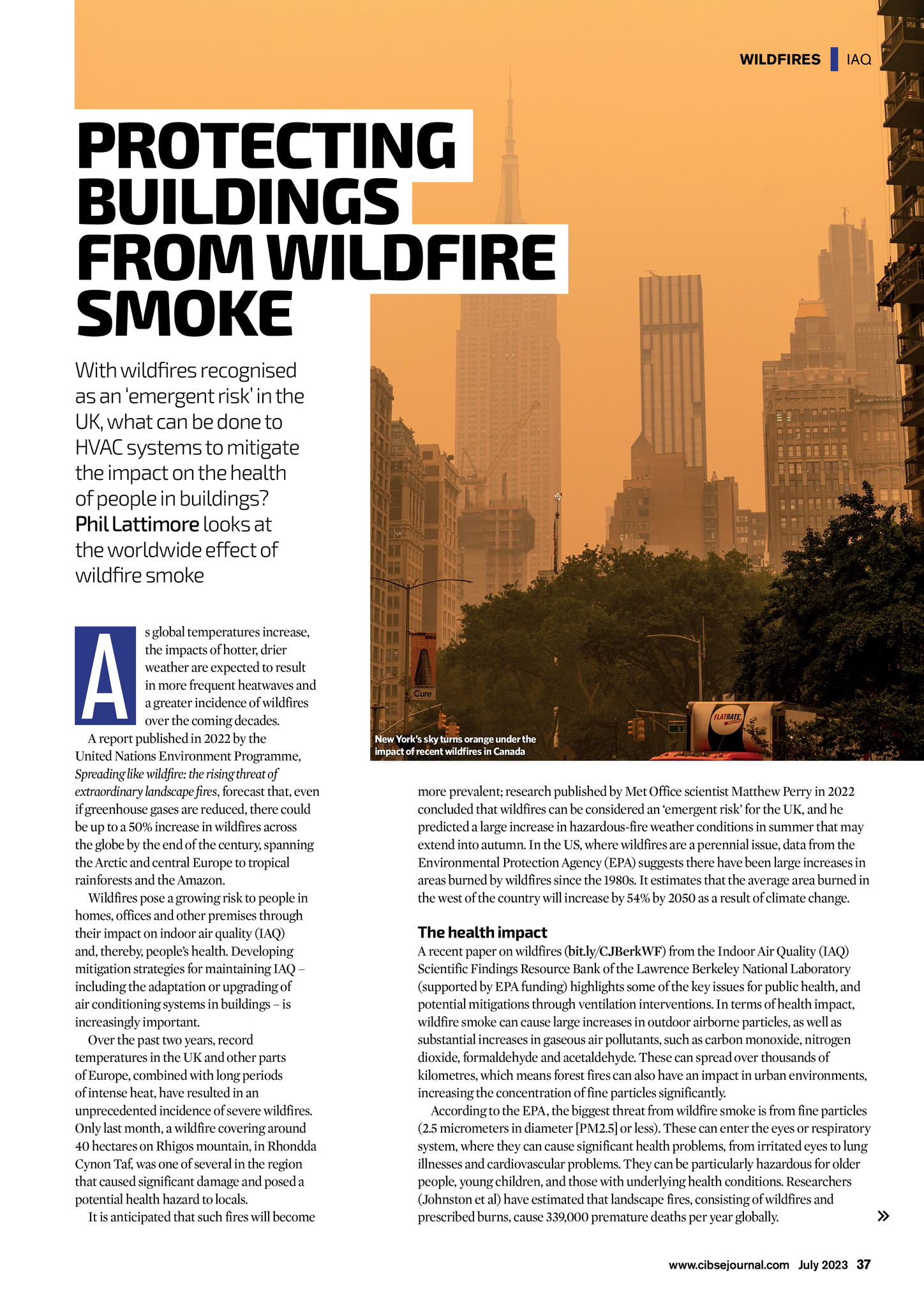

WILDFIRES | IAQ PROTECTING BUILDINGS FROM WILDFIRE SMOKE With wildfires recognised as an emergent risk in the UK, what can be done to HVAC systems to mitigate the impact on the health of people in buildings? Phil Lattimore looks at the worldwide effect of wildfire smoke A s global temperatures increase, the impacts of hotter, drier weather are expected to result in more frequent heatwaves and a greater incidence of wildfires over the coming decades. A report published in 2022 by the United Nations Environment Programme, Spreading like wildfire: the rising threat of extraordinary landscape fires, forecast that, even if greenhouse gases are reduced, there could be up to a 50% increase in wildfires across the globe by the end of the century, spanning the Arctic and central Europe to tropical rainforests and the Amazon. Wildfires pose a growing risk to people in homes, offices and other premises through their impact on indoor air quality (IAQ) and, thereby, peoples health. Developing mitigation strategies for maintaining IAQ including the adaptation or upgrading of air conditioning systems in buildings is increasingly important. Over the past two years, record temperatures in the UK and other parts of Europe, combined with long periods of intense heat, have resulted in an unprecedented incidence of severe wildfires. Only last month, a wildfire covering around 40 hectares on Rhigos mountain, in Rhondda Cynon Taf, was one of several in the region that caused significant damage and posed a potential health hazard to locals. It is anticipated that such fires will become New Yorks sky turns orange under the impact of recent wildfires in Canada more prevalent; research published by Met Office scientist Matthew Perry in 2022 concluded that wildfires can be considered an emergent risk for the UK, and he predicted a large increase in hazardous-fire weather conditions in summer that may extend into autumn. In the US, where wildfires are a perennial issue, data from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) suggests there have been large increases in areas burned by wildfires since the 1980s. It estimates that the average area burned in the west of the country will increase by 54% by 2050 as a result of climate change. The health impact A recent paper on wildfires (bit.ly/CJBerkWF) from the Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) Scientific Findings Resource Bank of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (supported by EPA funding) highlights some of the key issues for public health, and potential mitigations through ventilation interventions. In terms of health impact, wildfire smoke can cause large increases in outdoor airborne particles, as well as substantial increases in gaseous air pollutants, such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, formaldehyde and acetaldehyde. These can spread over thousands of kilometres, which means forest fires can also have an impact in urban environments, increasing the concentration of fine particles significantly. According to the EPA, the biggest threat from wildfire smoke is from fine particles (2.5 micrometers in diameter [PM2.5] or less). These can enter the eyes or respiratory system, where they can cause significant health problems, from irritated eyes to lung illnesses and cardiovascular problems. They can be particularly hazardous for older people, young children, and those with underlying health conditions. Researchers (Johnston et al) have estimated that landscape fires, consisting of wildfires and prescribed burns, cause 339,000 premature deaths per year globally. www.cibsejournal.com July 2023 37