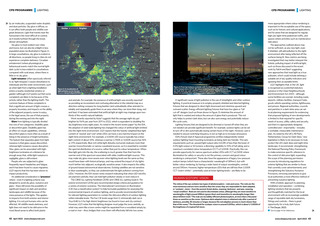

CPD PROGRAMME | LIGHTING by air molecules, suspended water droplets and dust particles. Sky glow is diffuse, so it can affect both people and wildlife over great distances. Light that travels near the horizontal is the most difficult to control, as it travels furthest through the lower, denser atmosphere. Sky glow is most evident over cities and towns, but can also be a blight in less populated areas (as illustrated in Figure 2). In large conurbations, sky glow is evident in all directions, so people living in cities do not experience complete darkness. Circadian entrainment (where physiological or behavioural events match the normal lightdark cycle) is less evident in conurbations compared with rural areas, where there is little or no sky glow. Light nuisance (often speciously referred to as light trespass) causes disturbance to individuals and the wider environment, such as when light from a lighting installation enters a nearby residential window or garden (although LG21 points out that some complaints are likely to be because of the activity rather than the lighting itself). The common feature of these complaints is that a significant amount of light crosses a property boundary and impacts on the ability of the adjacent property owner to enjoy, in the legal sense, the use of that property during the evening and into the night. Glare from lighting is typically divided into one of two categories: disability glare or discomfort glare. Disability glare has an effect on visual capabilities, whereas discomfort glare is more often as a result of being in the presence of bright luminaires. The feature that separates glare from light nuisance is that glare causes discomfort, whereas light nuisance causes disruption. Also, glare can be associated with highbrightness luminaires at a distance far enough away that, while light nuisance is negligible, glare is still evident. People who are subjected to glare frequently report headaches and fatigue, and it has been found to cause migraines. LG21 reports that this has been shown to impact productivity. An additional consideration is presence, where even if a lighting scheme was designed to avoid sky glow, nuisance and glare there still exists the possibility of significant impact on dark and sensitive landscapes and wildlife because of the mere presence of the lights. This applies to impacts from both exterior and interior lighting. It is not just humans who can be affected. All wildlife needs darkness, and light does not need to be obtrusive in the most literal sense to affect both plants 42 April 2023 www.cibsejournal.com Darker < - - - - - > Brighter Figure 2: A visualisation of light pollution across Europe (Source: bit.ly/CJApr23CPD5) and animals. For example, the presence of artificial light was recently reported2 as providing an inconsistent and confusing alternative to the celestial map as a direction-setting compass for dung beetles (and undoubtedly other animals) to reliably and repeatedly guide them to an area where they can store their dung, rest and feed. It has been estimated that artificial light at night may impinge upon twothirds of the worlds natural habitats. Work recently reported by Kyba3 suggests that the average night sky got brighter by 9.6% per year from 2011 to 2022, which is equivalent to doubling the sky brightness every eight years. As noted in the recent review paper4 by the IDA, the adoption of solid-state lighting has changed the colour of artificial light emitted into the night-time environment. LG21 reports that the heavily-weighted blue light content of neutral and cool white LEDs can have a very harmful impact on the night-time environment. For example, a 4,000K LED source typically has a bluelight content of about 33%, whereas a warmer 2,700K or 3,000K source has 16% or 21% respectively. Blue-rich white light disturbs nocturnal creatures more than warmer monochromatic or narrow-waveband sources, so it is essential to consider the spectral distribution of a source, rather than just its colour temperature. When blue light gets into the sky, the scattering is much greater than that from the warmer end of the spectrum associated with older, traditional light sources. This may make sky glow more severe even when lighting levels are the same as they would have been with historical lamps, and may extend the impact of city lights much farther into adjacent, ecologically sensitive areas. It also impacts the utility of ground-based astronomical observatories. Existing satellites are not sensitive to blue wavelengths, so they can underestimate the light pollution coming from LEDs.3 However, the IDA review notes research indicating that when LED retrofits are planned carefully, they can hold light pollution steady or even reduce it. The CIBSE SLL Lighting Handbook (2018) and CIBSE SLL Lighting Guide 6: The exterior environment (2016) give recommended design criteria and guidance for a variety of exterior scenarios. The International Commission on Illumination (CIE) has a classification system5 to help formulate guidelines for assessing the environmental impacts of outdoor lighting, and to provide recommended limits for relevant lighting parameters to contain the obtrusive effects of outdoor lighting within tolerable levels. The five CIE levels range from 0, intrinsically dark (as in Ynys Enlli) to 5 for high district brightness (as found in town and city centres). However, LG21 notes that the lighting designer must judge the zone carefully, as what may seem like a town centre might be separated from a woodland simply by a road or river thus, bridges that cross them will effectively fall into two zones.