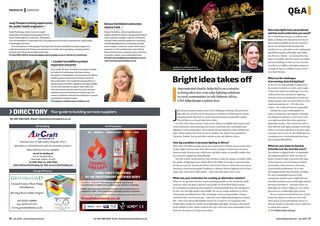

Q&A How many lights have you produced, and how much carbon have you saved? Zambia is one of the countries in which SolarAid is focusing its efforts John Keane Bright idea takes off International charity SolarAid is on a mission to bring ultra-low-cost solar lighting solutions to rural communities in sub-Saharan Africa. CEO John Keane explains how J ohn Keane became acutely aware of the challenges of living without electric light after he moved to rural Tanzania as a volunteer in 2000 and saw people using hazardous alternatives, such as kerosene lamps and paraffin candles. This led him to co-found SolarAid in 2006. As CEO of the charity, Keane works across Africa to establish solar projects and social enterprises, and encourage innovation, to provide safe, sustainable solar lighting to rural communities. This includes the development of the SM100 solar light, which retails at $5. From its start in Malawi, the charity has expanded to Tanzania, Zambia, Kenya and other nations across sub-Saharan Africa. How big a problem is kerosene lighting in Africa? More than 578 million people across the continent live without access to electricity. To have light in homes after dark often means turning to rudimentary, kerosene lanterns made from tin cans, which spew out black smoke, or paraffin candles that are expensive, dangerous and polluting. Not only is there an obvious fire risk, but there is also the impact on health, while the quality of lighting is poor, which affects the ability of people to read and study. Its also an issue for schools and clinics. One in four clinics in Africa has no access to electricity, which means quality healthcare is limited. Electric lighting with LEDs is clean, safe, convenient, high-quality and, with solar power, free to run. What was your motivation for creating an alternative solution? When we set up SolarAid, there wasnt anything suitable on the market for smallscale use. Solar was quite expensive and usually involved fairly large systems. So, we looked at producing solar lamps for rural households that were designed to be low-cost, but high-quality and reliable. We set up cottage industries in Africa with people assembling them. The technology was becoming smaller, cheaper and better, but, even 10 years ago when the cost of lights had dropped to around $10 there was still an affordability barrier. So, in 2013-14, we teamed up with Yingli Solar to make the worlds most affordable solar light. This led to the launch of the SM100 in 2016, which retails for $5. Our work with rural communities feeds back into the improved design of products. Weve distributed around 2.2 million solar lights, working with entrepreneurs who we have helped establish across the continent. But we are all about kick-starting solar markets, so we want others to be making and distributing quality, affordable solar lights too. We are a charity we can lead the way, show its possible, and then others can follow and start building on that success. In terms of carbon, 2.2 million solar lights equates to a rough saving of 2.2 million tonnes of CO2 over their lifetime. What are the challenges of promoting SolarAid lighting? In the UK, its to get people to understand the context in which we work, and to make it clear how much of a challenge it is to live without electricity and electric lighting. In terms of the environments in which our teams operate, these are often hard-to-reach rural communities, so if its the rainy season the roads can become impassable. Another key issue is affordability. In many communities, the majority of people are subsistence farmers, so they have to be very judicious about how they spend any disposable income. They need to be able to trust that the solar light is going to work and, if there are issues, that there is an after-sales, customer care service. So, the challenges are creating access, creating demand and trust, and creating affordability. What are your plans to develop SolarAid over the next few years? Our mission is aligned with UN sustainable development goals; by 2030, we want no home, school or clinic to be left in the dark. At the moment, were focusing on Malawi and Zambia, where access to electricity is particularly problematic. Were also developing models that prioritise reaching the most marginalised sectors of the community; models such as light libraries that allow people to access solar light without having to purchase it and ones where we help light up a whole village, so every home gets access to a multi-light solar system. We are trying to break the barriers of price point. Our objective is then to work with other actors across sub-Saharan Africa, so that the models we develop can be replicated to widen their impact. Visit https://solar-aid.org/ www.cibsejournal.com July 2022 57 CIBSE July 22 pp57 Q&A.indd 57 24/06/2022 15:22