Findings from Innovate UK’s four-year Building Performance Evaluation (BPE) programme show that, on average, non-domestic buildings use 3.6 times more energy than predicted by their designers. The results, revealed last month, are broadly the same for domestic buildings; while some work really well, there is evidence of a yawning gap in performance for the majority. Average carbon emissions from the 350 homes studied, were 2.6 times higher than the average design intent.

The BPE programme also identified indoor air quality (IAQ) and overheating concerns in many of the buildings studied. In all cases, there were very significant lessons for the building services engineers.

Wimbish Passivhaus development was one of the few that performed well

So what was the difference between projects that had a small performance gap and those for which it was much wider? This question was asked earlier this year at a workshop of Innovate UK experts, appointed to act as critical friends to teams involved in BPE projects. The event, organised by the Knowledge Transfer Network (KTN), built on a National Energy Foundation (NEF) meta study of the performance of BPE projects involving a social landlord (see Figure 1).

After discussion with the Innovate UK experts, it was clear there were some common success factors associated with the best-performing buildings, including: committed clients; integrated design; clear documentation; and extended handover periods. (See panel, ‘Success factors’).

Ventilation and indoor air quality

The BPE projects showed that, although we are increasingly able to ‘design tight’, we haven’t yet learned to ‘ventilate right’. A meta study on ventilation, associated with the BPE programme, will be published shortly – as, one day, will the results of an ongoing indoor air quality study by the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG). Ahead of these, the experts workshop identified multiple issues from the BPE programme:

The Hastoe Housing Association affordable homes were designed by Parsons + Whittley

BPE air pressurisation tests showed that, sometimes, the fabric is much tighter than expected while, on other occasions, it is substantially leakier. The conundrum is that – in those cases where a building is substantially more leaky than planned – there is no longer a requirement for mechanical ventilation to provide the requisite levels of ventilation. Where buildings are much tighter than planned, the level of background air infiltration is sometimes such that regulations require additional ventilation systems to ensure good air quality. The Passivhaus buildings assessed under the BPE programme delivered the closest correlation between design and practice.

The BPE tests were often significantly different from compliance tests, perhaps reflecting the practice – sometimes applied ahead of the formal pressurisation test – of blocking gaps that would otherwise cause the building to fail. Based on the BPE data, the effectiveness of such fixes may be short-lived.

Where multiple airtightness testing was undertaken near the start and end of each project, there was no consistent finding. Airtightness could increase, stay broadly consistent, and even, occasionally, fall. The construction type, materials, and approach to maintaining airtightness during occupancy appeared to be key principles.

It was clear that, in practice, mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) systems were often not functioning in line with their specification (airflow rates and efficiencies) and the same issues were found with mechanical extract ventilation (MEV). Where MVHR and MEV systems performed poorly, the underlying cause was a combination of design, installation, commissioning and operating issues.

Success factors

Committed client and owners: Where housing associations were the client, their track record in developing environmentally sensitive buildings – and their commitment to make these buildings work – were important factors. Having occupants who were committed to ensuring successful operation was also key

Quality: Particularly where new technologies or construction techniques are being employed, supply chain experience and a systemic approach to quality were important. New technologies or approaches coupled with few (if any) validation checks usually led to a large performance gap. Buildings constructed to a Passivhaus standard tended to operate much closer to design intent than most other buildings studied. The Passivhaus approach to quality appeared to result in greater attention to design and construction detail, although it was also usually associated with committed clients

An integrated design approach and manageable complexity: This was most apparent in its absence as a risk factor. Services ‘bolted on’ to meet a regulatory or labelling goal almost inevitably underperformed. Usually, simpler systems worked best, although the Hastoe Housing project showed how a fairly sophisticated set of systems could be made to work together where there was experience and commitment. A failure to engage building services engineers at an early stage had foreseeable consequences

Handover: Where systems such as MVHR, biomass boilers and solar water heating were new to occupiers and facilities teams, good, simple documentation, and a handover period with extended support, were important success factors. Homes that occupants could use without having to master systems first, were identified by the experts as the most successful.

Examples of operating issues included occupants turning off units, or not using them correctly, because of noise, perceived energy cost, or lack of understanding. Filters not being cleaned/changed was another issue, as was new carpets blocking air pathways through the building.

Not all MVHR systems were designed to be readily accessed for maintenance; flexible ductwork was sometimes used – and abused – in excess quantities. Nor were all control systems intuitive for occupiers. Passive ventilation was also not a panacea for good air quality; for example, some occupants blocked the use of trickle ventilators, or were unwilling to open windows.

On top of all this, actual occupancy rates and behaviour is often different from that assumed at the design stage.

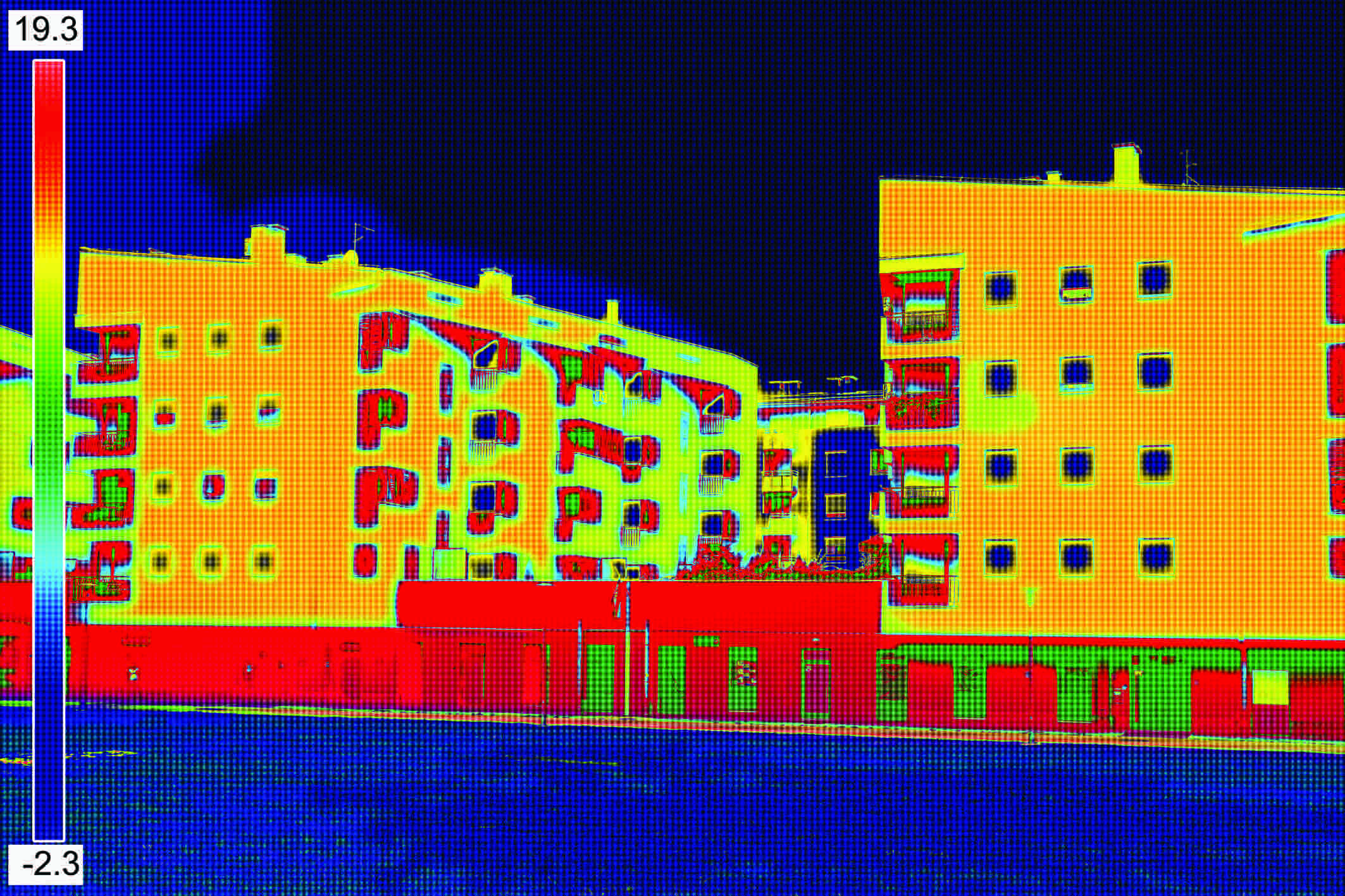

Infrared thermovision image showing lack of thermal insulation on a residential building

This led one workshop participant to suggest that the only effective way forward was to link future ventilation systems to a measurement of IAQ, and to use this to alert occupants as to poor air quality.

Many of the BPE projects identified overheating as an issue. There was a common failure to design effectively to use building mass and minimise solar gain, and there were instances where building services engineers could have done more to mitigate solar overheating. These included properly insulating services and ensuring MVHR units both have a summer bypass fitted, and operate as per design intent. Limitations on window opening also restricted occupant control of overheating.

Although there were instances of significant variances between ‘as designed’ and ‘as built’ air permeability and fabric insulation values, a major source of the performance gap was building services. Most low or zero carbon technologies and community heating schemes performed less well than more traditional systems. This perhaps reflects the lack of client and supply chain experience. Photovoltaics (PV) was a general exception to this, with most systems performing close to expectations – although there were exceptions even here.

Reports and seminar

Innovate UK’s BPE programme included more than 50 studies of 350 homes. Reports are available on the Building Data Exchange and the Knowledge Transfer Network’s (KTN’s) BPE connect site.

KTN is arranging a free seminar on housing issues arising from the BPE programme. To be on the invite list, email valeria.branciforti@ktn-uk.org

Generally, it was suggested, a traditional procurement route appeared to provide better performance outcomes than design-build. Value engineering didn’t always result in poor outcomes, although its implications in terms of realised building performance were not always thought through. A soft landings approach to housing development was also seen as being important.

Perhaps the key lesson arising from the programme isn’t so much the various performance gaps, occupant behaviours, and impact of new technology, but how far organisations are willing and able to learn and adapt. As one participant at the experts workshop observed: ‘The organisations benefiting the most are those that have learned from the BPE programme, and who are changing practice as a result.’